RFDiffusion: De Novo Protein Structure Generation

This is Lecture 5 of the Protein & Artificial Intelligence course (Spring 2026), co-taught by Prof. Sungsoo Ahn and Prof. Homin Kim at KAIST. The lecture builds on the diffusion model foundations introduced in Lecture 2 (Generative Models) and the structure prediction concepts from Lecture 4 (AlphaFold). Of all the lectures in this course, this one is the most mathematically intensive, requiring careful treatment of Lie groups, manifold-valued noise processes, and equivariant neural network design.

1. Introduction: The Dream of De Novo Protein Design

For decades, protein engineers have faced a fundamental asymmetry. Predicting how a known sequence folds into a three-dimensional structure is now largely solved, thanks to AlphaFold and related methods (Lecture 4). But the reverse problem — designing an entirely new protein that folds into a desired shape and performs a specified function — has remained far more difficult.

Consider the contrast with other engineering disciplines. A civil engineer does not begin by finding a bridge in nature and copying it. She specifies the span, the load, and the material constraints, then designs a structure that meets those requirements. De novo protein design aspires to the same workflow: specify what you want the protein to do, then compute a structure that accomplishes it.

In July 2023, a team led by David Baker at the University of Washington published RFDiffusion, a method that brought this aspiration within reach (missing reference). RFDiffusion generates novel protein backbones by learning to reverse a noise process — the same core idea behind image generation models like DALL-E and Stable Diffusion, but adapted for the unique geometric constraints of molecular structures. The designed proteins were not theoretical curiosities: when synthesized in the laboratory, they folded into the predicted structures and performed their intended functions.

What makes the method technically distinctive is its treatment of geometry. A protein backbone is not an image or a point cloud. Each amino acid residue carries both a position and an orientation, and the physics of the molecule is unchanged if you rotate or translate the entire structure. Handling these geometric properties correctly requires mathematical machinery from Lie group theory — specifically, the groups \(SO(3)\) (rotations) and \(SE(3)\) (rotations plus translations).

This lecture develops that machinery from the ground up, shows how it leads to a principled diffusion process on protein frames, and explains how the resulting model can be conditioned to solve practical design problems.

Roadmap

The following table maps each section of this lecture to the question it answers.

| Section | Topic | Why It Is Needed |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | SE(3) equivariance | Proteins are geometric objects; a model that ignores this wastes data and generalizes poorly |

| 3 | Rotation representations | Before diffusing rotations, we need a numerically stable way to represent them |

| 4 | Frame representation | Each residue is a rigid body; frames are the natural state space for protein backbones |

| 5 | IGSO(3) distribution | Standard Gaussian noise is undefined on the rotation manifold; IGSO(3) fills this gap |

| 6 | SE(3) diffusion process | Combining translational and rotational noise into a single forward process |

| 7 | Equivariant neural networks | The denoiser must respect SE(3) symmetry by construction |

| 8 | RFDiffusion architecture | How RoseTTAFold is adapted from structure prediction to structure generation |

| 9 | Conditional generation | Motif scaffolding, binder design, and other practical applications |

| 10 | Training and loss functions | How the model learns to denoise on SE(3) |

| 11 | Sampling and generation | The reverse process that produces novel protein backbones |

| 12 | Experimental validation | Evidence that the designed proteins actually work |

| 13 | Exercises | Practice problems spanning mathematics and implementation |

2. Why Geometry Matters: The Case for SE(3) Equivariance

Proteins Do Not Have a Preferred Orientation

Suppose you determine the crystal structure of an enzyme. You record the coordinates of every atom. Now a colleague in another laboratory solves the same structure, but their crystal happened to grow in a different orientation. Their coordinates differ from yours by a rotation and a translation, yet the two structures are identical in every biological sense. The enzyme catalyzes the same reaction. Its binding affinity for a substrate is unchanged. Its stability is the same.

This observation has a name: the biological properties of a protein are invariant under the group of rigid-body transformations in three-dimensional space. That group is called \(SE(3)\), the Special Euclidean group in three dimensions1. An element of \(SE(3)\) is a pair \((R, \vec{t})\) where \(R\) is a \(3 \times 3\) rotation matrix and \(\vec{t}\) is a translation vector in \(\mathbb{R}^3\). It acts on a point \(\vec{x} \in \mathbb{R}^3\) by

\[T \cdot \vec{x} = R\vec{x} + \vec{t}.\]From Invariance to Equivariance

flowchart LR

subgraph Invariant["Invariance (scalar output)"]

direction TB

P1["Protein\n(original)"] --> F1["f(x)"] --> S1["Energy = −42.3"]

RP1["Rotated\nProtein"] --> RF1["f(Rx)"] --> RS1["Energy = −42.3"]

S1 -.- RS1

end

subgraph Equivariant["Equivariance (geometric output)"]

direction TB

P2["Protein\n(original)"] --> F2["f(x)"] --> S2["Structure\n(output)"]

RP2["Rotated\nProtein"] --> RF2["f(Rx)"] --> RS2["Rotated\nStructure\n= R · f(x)"]

end

style S1 fill:#e8f5e9,stroke:#4CAF50

style RS1 fill:#e8f5e9,stroke:#4CAF50

style S2 fill:#e8f4fd,stroke:#2196F3

style RS2 fill:#e8f4fd,stroke:#2196F3

Invariance tells us what properties should not change under transformations. But a generative model does not just compute scalar properties — it outputs structures, which are geometric objects that should transform when the input transforms.

If you rotate the conditioning information fed to a protein generator, the generated structure should rotate by the same amount. This stronger requirement is called SE(3) equivariance. A function \(f\) is equivariant with respect to a group \(G\) if, for every group element \(g \in G\),

\[f(g \cdot x) = g \cdot f(x).\]In words: applying the transformation before the function gives the same result as applying it after.

Why Not Just Augment the Data?

A natural objection is: why build equivariance into the architecture when we could simply augment the training data with random rotations and translations?

Data augmentation does help, but it has three limitations compared to architectural equivariance.

Data efficiency. An equivariant model knows, by construction, that all orientations of a protein are equivalent. It never needs to “learn” this from examples. A non-equivariant model must see the same structure from many orientations before it generalizes, which wastes precious training data.

Guaranteed generalization. No amount of data augmentation can guarantee that a model has perfectly learned the symmetry. An equivariant architecture satisfies the symmetry exactly, for every possible input, including inputs far from the training distribution.

Physically meaningful representations. When a model is equivariant, its internal feature vectors have well-defined transformation laws. Vectors transform like vectors; scalars remain scalars. This makes the representations more interpretable and more likely to capture physically meaningful relationships.

3. The Language of Rotations

Before we can add noise to the orientation of a protein residue, we need a concrete way to represent rotations. This turns out to be more subtle than it first appears, and the choice of representation has significant consequences for numerical stability.

A rotation in three dimensions has three degrees of freedom. You can think of these as the three angles needed to orient a rigid body: pitch, yaw, and roll. Yet the four most common representations use different numbers of parameters.

Rotation Matrices

A rotation is a \(3 \times 3\) orthogonal matrix \(R\) with determinant \(+1\). It acts on a vector \(\vec{v}\) by matrix multiplication: \(\vec{v}' = R\vec{v}\). The set of all such matrices forms the group \(SO(3)\)2.

Rotation matrices are direct and easy to compose (matrix multiplication), but they use nine numbers to describe three degrees of freedom. The six constraints (orthogonality and unit determinant) must be enforced explicitly, which can cause numerical drift in iterative algorithms.

Euler Angles

Three angles \((\phi, \theta, \psi)\) describe successive rotations about coordinate axes. This representation is minimal (three numbers for three degrees of freedom) and intuitive, but it suffers from gimbal lock: at certain orientations, two of the three axes align, and the representation loses a degree of freedom. Gimbal lock causes discontinuities that are catastrophic for gradient-based optimization.

Axis-Angle Representation

Any rotation can be described by a unit vector \(\hat{n}\) (the axis) and a scalar \(\omega\) (the angle). The combined representation \(\vec{\omega} = \omega \hat{n}\) is a three-dimensional vector whose direction is the rotation axis and whose magnitude is the rotation angle.

This representation is minimal and geometrically intuitive. The axis-angle representation lives in a tangent space — a flat approximation of the curved rotation space near the identity rotation. Mathematicians call this tangent space the Lie algebra \(\mathfrak{so}(3)\), and it will be important when we define noise processes. Its main drawback is a singularity at \(\omega = 0\), where the axis is undefined.

The conversion from axis-angle to rotation matrix uses the Rodrigues formula:

\[R = I + \sin(\omega) K + (1 - \cos(\omega)) K^2,\]where \(K\) is the skew-symmetric matrix constructed from the axis vector \(\hat{n}\), and \(I\) is the \(3 \times 3\) identity matrix3.

import torch

import numpy as np

def skew_symmetric(v):

"""

Construct the 3x3 skew-symmetric matrix [v]_x from a 3D vector v.

For a vector v = (v1, v2, v3), the skew-symmetric matrix satisfies

[v]_x @ w = v x w (cross product) for any vector w.

Args:

v: [..., 3] axis vectors (e.g., rotation axes for each residue)

Returns:

K: [..., 3, 3] skew-symmetric matrices

"""

batch_shape = v.shape[:-1]

zero = torch.zeros(*batch_shape, device=v.device)

return torch.stack([

torch.stack([zero, -v[..., 2], v[..., 1]], dim=-1),

torch.stack([v[..., 2], zero, -v[..., 0]], dim=-1),

torch.stack([-v[..., 1], v[..., 0], zero ], dim=-1)

], dim=-2)

def axis_angle_to_rotation_matrix(axis_angle):

"""

Convert axis-angle vectors to rotation matrices via the Rodrigues formula.

Each residue's orientation perturbation can be expressed as a rotation

by angle omega about axis n_hat. This function converts that compact

representation into the full 3x3 matrix needed for coordinate transforms.

Args:

axis_angle: [..., 3] vectors where direction = axis, magnitude = angle

Returns:

R: [..., 3, 3] rotation matrices

"""

angle = axis_angle.norm(dim=-1, keepdim=True) # rotation angle omega

axis = axis_angle / (angle + 1e-8) # unit axis n_hat

K = skew_symmetric(axis) # [..., 3, 3]

I = torch.eye(3, device=axis_angle.device).expand(

*axis_angle.shape[:-1], 3, 3

)

sin_angle = torch.sin(angle).unsqueeze(-1)

cos_angle = torch.cos(angle).unsqueeze(-1)

# Rodrigues: R = I + sin(omega) * K + (1 - cos(omega)) * K^2

R = I + sin_angle * K + (1 - cos_angle) * torch.einsum(

'...ij,...jk->...ik', K, K

)

return R

Quaternions

A unit quaternion \(q = (w, x, y, z)\) with \(w^2 + x^2 + y^2 + z^2 = 1\) provides a four-parameter representation of a rotation. The extra parameter (four instead of three) buys important benefits: quaternions are free of singularities, interpolate smoothly, and compose efficiently. They also have a double-cover property — \(q\) and \(-q\) represent the same rotation — which must be handled carefully but is not a practical obstacle.

RFDiffusion uses quaternions internally for numerical stability. Here is the conversion between quaternions and rotation matrices:

def quaternion_to_rotation_matrix(q):

"""

Convert unit quaternions to rotation matrices.

Quaternions avoid gimbal lock and provide numerically stable

interpolation between orientations --- critical when iteratively

updating residue frames during diffusion.

Args:

q: [..., 4] quaternions in (w, x, y, z) convention

Returns:

R: [..., 3, 3] rotation matrices

"""

# Normalize to unit quaternion (guards against numerical drift)

q = q / (q.norm(dim=-1, keepdim=True) + 1e-8)

w, x, y, z = q.unbind(-1)

R = torch.stack([

torch.stack([1 - 2*y*y - 2*z*z, 2*x*y - 2*w*z, 2*x*z + 2*w*y], dim=-1),

torch.stack([2*x*y + 2*w*z, 1 - 2*x*x - 2*z*z, 2*y*z - 2*w*x], dim=-1),

torch.stack([2*x*z - 2*w*y, 2*y*z + 2*w*x, 1 - 2*x*x - 2*y*y], dim=-1)

], dim=-2)

return R

def rotation_matrix_to_quaternion(R):

"""

Convert rotation matrices to unit quaternions.

This uses the Shepperd method based on the matrix trace. The

implementation handles the common case where the trace is positive;

production code should also handle degenerate cases.

Args:

R: [..., 3, 3] rotation matrices

Returns:

q: [..., 4] unit quaternions (w, x, y, z)

"""

trace = R[..., 0, 0] + R[..., 1, 1] + R[..., 2, 2]

w = torch.sqrt(torch.clamp(1 + trace, min=1e-8)) / 2

x = (R[..., 2, 1] - R[..., 1, 2]) / (4 * w + 1e-8)

y = (R[..., 0, 2] - R[..., 2, 0]) / (4 * w + 1e-8)

z = (R[..., 1, 0] - R[..., 0, 1]) / (4 * w + 1e-8)

q = torch.stack([w, x, y, z], dim=-1)

return q / (q.norm(dim=-1, keepdim=True) + 1e-8)

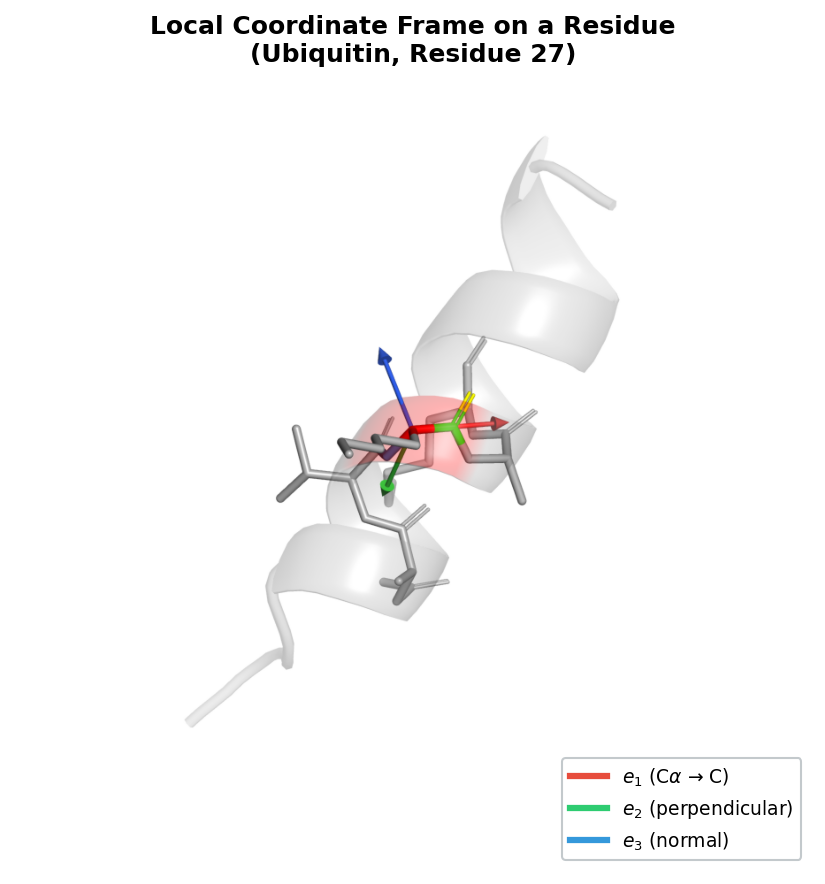

4. Each Amino Acid Has Its Own Coordinate System

The Frame Representation

A protein backbone consists of a chain of amino acid residues. Each residue contains three backbone atoms — nitrogen (N), alpha carbon (\(\text{C}_\alpha\)), and carbonyl carbon (C) — that form a relatively rigid unit4. Two pieces of information fully specify the placement of this unit in space:

- Position: the location of the \(\text{C}_\alpha\) atom, a vector \(\vec{t}_i \in \mathbb{R}^3\).

- Orientation: the direction the residue “faces,” encoded as a rotation matrix \(R_i \in SO(3)\) that maps from a canonical local coordinate system to the global frame.

Together, the pair \((R_i, \vec{t}_i)\) defines a rigid-body frame for residue \(i\).

graph LR

subgraph "Residue Frame T_i = (R_i, t_i)"

direction TB

CA["Cα\n(origin = t_i)"]

N["N"]

C["C"]

X["x-axis"]

Y["y-axis"]

Z["z-axis"]

N --- CA --- C

CA -.->|"e₁"| X

CA -.->|"e₂"| Y

CA -.->|"e₃"| Z

end

subgraph "Protein Backbone"

F1["Frame T₁"] --> F2["Frame T₂"] --> F3["Frame T₃"] --> F4["..."] --> FL["Frame T_L"]

end

style CA fill:#e74c3c,color:white

style N fill:#4a90d9,color:white

style C fill:#2ecc71,color:white

style F1 fill:#9b59b6,color:white

style F2 fill:#9b59b6,color:white

style F3 fill:#9b59b6,color:white

style FL fill:#9b59b6,color:white

The set of all such pairs forms the group \(SE(3)\): a transformation \(T = (R, \vec{t})\) acts on a point \(\vec{x}\) by

\[T \cdot \vec{x} = R\vec{x} + \vec{t}.\]A protein backbone with \(L\) residues is therefore a sequence of \(L\) frames:

\[\mathcal{T} = \{T_1, T_2, \ldots, T_L\}, \quad T_i = (R_i, \vec{t}_i) \in SE(3).\]This representation is powerful for three reasons. First, it is complete: given all \(L\) frames plus the amino acid identities, we can reconstruct the full atomic structure (backbone atoms are placed by the frame; side-chain atoms are placed by the identity and local geometry). Second, it is compact: only \(6L\) degrees of freedom (three for position, three for orientation, per residue). Third, it is geometrically natural: the relative transformation between two frames, \(T_i^{-1} \circ T_j\), captures the intrinsic geometry of the residue pair independent of global orientation.

Implementation

class RigidTransform:

"""

Rigid body transformation (rotation + translation) for protein residues.

Each residue in a protein backbone is described by a frame T = (R, t),

where R is a 3x3 rotation matrix defining the local coordinate system

and t is a 3D vector giving the C-alpha position.

"""

def __init__(self, rotations, translations):

"""

Args:

rotations: [..., 3, 3] rotation matrices (one per residue)

translations: [..., 3] C-alpha positions (one per residue)

"""

self.rots = rotations

self.trans = translations

@classmethod

def identity(cls, batch_shape, device='cpu'):

"""Create identity frames (no rotation, origin position)."""

rots = torch.eye(3, device=device).expand(*batch_shape, 3, 3).clone()

trans = torch.zeros(*batch_shape, 3, device=device)

return cls(rots, trans)

def compose(self, other):

"""

Compose two transformations: self followed by other.

Result: (R1 @ R2, R1 @ t2 + t1)

"""

new_rots = torch.einsum('...ij,...jk->...ik', self.rots, other.rots)

new_trans = (

torch.einsum('...ij,...j->...i', self.rots, other.trans)

+ self.trans

)

return RigidTransform(new_rots, new_trans)

def apply(self, points):

"""Apply transformation to points: R @ x + t."""

return (

torch.einsum('...ij,...j->...i', self.rots, points) + self.trans

)

def invert(self):

"""Compute inverse transformation: (R^T, -R^T @ t)."""

inv_rots = self.rots.transpose(-1, -2)

inv_trans = -torch.einsum('...ij,...j->...i', inv_rots, self.trans)

return RigidTransform(inv_rots, inv_trans)

def to_tensor_7(self):

"""Convert to 7D representation (quaternion + translation)."""

quat = rotation_matrix_to_quaternion(self.rots)

return torch.cat([quat, self.trans], dim=-1)

@classmethod

def from_tensor_7(cls, tensor):

"""Create from 7D representation (quaternion + translation)."""

quat = tensor[..., :4]

trans = tensor[..., 4:]

rots = quaternion_to_rotation_matrix(quat)

return cls(rots, trans)

The compose method deserves special attention. When we compose two rigid-body transformations \(T_1 = (R_1, \vec{t}_1)\) and \(T_2 = (R_2, \vec{t}_2)\), the result is

This is not commutative: \(T_1 \circ T_2 \neq T_2 \circ T_1\) in general. The order matters because rotations are applied to subsequent translations. This non-commutativity is a fundamental feature of \(SE(3)\) and has direct consequences for how we apply frame updates during denoising.

5. Diffusion Meets Geometry: The IGSO(3) Distribution

The Challenge of Adding Noise to Rotations

Recall from Lecture 2 (Generative Models) how standard diffusion works for data in Euclidean space. Given a clean data point \(x_0\), we define a forward process that gradually adds Gaussian noise:

\[x_t = \sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t} \, x_0 + \sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}_t} \, \epsilon, \quad \epsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(0, I),\]where \(\bar{\alpha}_t\) is a noise schedule parameter that decreases from 1 (clean) to 0 (pure noise) as the timestep \(t\) increases.

This works perfectly for the translational component of protein frames — positions \(\vec{t}_i\) live in \(\mathbb{R}^3\), and Gaussian noise in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) is well defined.

But rotations live on a manifold — a space that is locally flat (like a small patch of a sphere looks flat) but globally curved. Specifically, rotations live on the manifold \(SO(3)\), which is not a Euclidean space. You cannot “add” Gaussian noise to a rotation matrix and expect the result to remain a valid rotation. The matrix \(R + \epsilon\) (with \(\epsilon\) drawn from a matrix-valued Gaussian) is not orthogonal, does not have determinant one, and does not represent a rotation at all.

We need a noise distribution that is native to the rotation manifold.

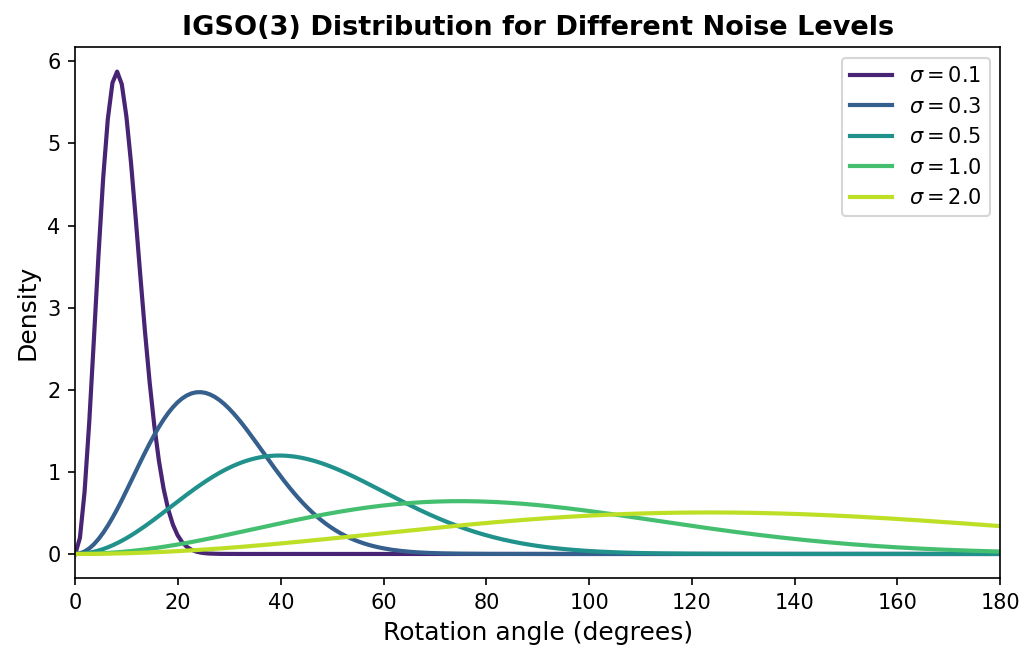

The Isotropic Gaussian on SO(3)

The solution is the Isotropic Gaussian distribution on SO(3), abbreviated IGSO(3)5. This distribution plays the same role for rotations that the standard Gaussian plays for Euclidean data: it provides a way to add controlled, isotropic noise that smoothly interpolates between the identity (no noise) and the uniform distribution (maximum noise).

Here is the intuition. Imagine holding a pointer that starts aimed at the north pole of a sphere. A sample from IGSO(3) with parameter \(\sigma\) rotates this pointer by a random angle \(\omega\) drawn from a distribution that is approximately Gaussian with standard deviation \(\sigma\), around a uniformly random axis.

- When \(\sigma\) is small, the perturbation is small: the pointer stays near the north pole.

- When \(\sigma\) is large, the pointer can end up anywhere on the sphere.

- In the limit \(\sigma \to \infty\), the distribution becomes the uniform (Haar) measure over \(SO(3)\): every orientation is equally likely.

Formally, the density of IGSO(3) with concentration parameter \(\sigma\) at a rotation \(R\) is

\[p(R \mid \sigma) \propto \sum_{\ell=0}^{\infty} (2\ell + 1) \exp\!\left(-\frac{\ell(\ell+1)\sigma^2}{2}\right) \chi_\ell(R),\]where \(\chi_\ell(R)\) is the character of the irreducible representation of \(SO(3)\) at degree \(\ell\)6. In practice, for the rotation angles relevant to protein diffusion, this is well approximated by a simpler expression that depends only on the rotation angle \(\omega\) of \(R\):

\[p(\omega \mid \sigma) \propto (1 - \cos \omega) \exp\!\left(-\frac{\omega^2}{2\sigma^2}\right).\]The \((1 - \cos \omega)\) factor accounts for the geometry of the rotation space — just as the surface area element of a sphere requires a \(\sin\theta\) factor, the “volume element” of \(SO(3)\) requires this correction. This geometric correction factor is called the Haar measure density on \(SO(3)\), expressed in the angle variable.

Sampling from IGSO(3)

Sampling from IGSO(3) is straightforward using the axis-angle decomposition:

- Draw a rotation angle \(\omega\) from a folded normal distribution with standard deviation \(\sigma\).

- Draw a rotation axis \(\hat{n}\) uniformly from the unit sphere \(S^2\).

- Convert the axis-angle pair \((\hat{n}, \omega)\) to a rotation matrix using the Rodrigues formula.

def sample_igso3(shape, sigma, device='cpu'):

"""

Sample rotation matrices from the Isotropic Gaussian on SO(3).

This is the rotational analogue of sampling from a Gaussian in

Euclidean space. Each sample is a random rotation whose angle

(roughly) follows a Gaussian with standard deviation sigma,

applied about a uniformly random axis.

Args:

shape: batch dimensions (e.g., (L,) for L residues)

sigma: noise level (scalar or broadcastable tensor);

small sigma -> small perturbations, large sigma -> near-uniform

device: torch device

Returns:

rotations: [*shape, 3, 3] sampled rotation matrices

"""

# Step 1: Sample rotation angle |omega| ~ folded normal(0, sigma^2)

omega = torch.abs(torch.randn(*shape, device=device) * sigma)

# Step 2: Sample rotation axis uniformly on the unit sphere S^2

axis = torch.randn(*shape, 3, device=device)

axis = axis / (axis.norm(dim=-1, keepdim=True) + 1e-8)

# Step 3: Convert to rotation matrix via Rodrigues formula

rotations = axis_angle_to_rotation_matrix(axis * omega.unsqueeze(-1))

return rotations

The key property of this sampling procedure is that the resulting distribution is isotropic: it treats all rotation axes equally. There is no preferred direction of perturbation, just as standard Gaussian noise in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) treats all spatial directions equally.

6. The Complete SE(3) Diffusion Process

With the IGSO(3) distribution in hand, we can define the full forward diffusion process for protein frames. The process treats the translational and rotational components separately, using the appropriate noise distribution for each.

Translational Diffusion

Translations live in \(\mathbb{R}^3\), so standard Gaussian diffusion applies directly. Given clean \(\text{C}_\alpha\) positions \(\vec{t}_0\) and a noise schedule parameter \(\bar{\alpha}_t\):

\[\vec{t}_t = \sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t} \, \vec{t}_0 + \sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}_t} \, \epsilon, \quad \epsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(0, I).\]def diffuse_translations(translations, t, noise_schedule):

"""

Add Gaussian noise to C-alpha positions.

Args:

translations: [..., 3] clean C-alpha positions

t: [...] diffusion timesteps in [0, 1]

noise_schedule: object providing alpha_bar(t)

Returns:

noisy_translations: [..., 3]

noise: [..., 3] the sampled Gaussian noise

"""

alpha_bar = noise_schedule.alpha_bar(t) # [..., 1]

noise = torch.randn_like(translations)

noisy = torch.sqrt(alpha_bar) * translations + torch.sqrt(1 - alpha_bar) * noise

return noisy, noise

Rotational Diffusion

Rotations live on \(SO(3)\), so we use IGSO(3). Given a clean rotation \(R_0\) and a noise level \(\sigma_t\), the noisy rotation is obtained by composing \(R_0\) with a random rotation sampled from IGSO(3):

\[R_t = R_{\text{noise}} \cdot R_0, \quad R_{\text{noise}} \sim \text{IGSO}(3; \sigma_t).\]Composition (matrix multiplication) replaces addition because \(SO(3)\) is a group, not a vector space. The noise rotation \(R_{\text{noise}}\) acts as a random perturbation applied to the clean orientation.

def diffuse_rotations(rotations, t, noise_schedule):

"""

Add IGSO(3) noise to residue orientations.

Unlike translations (where noise is added), rotational noise is

composed (multiplied) because SO(3) is a multiplicative group.

Args:

rotations: [..., 3, 3] clean rotation matrices

t: [...] diffusion timesteps in [0, 1]

noise_schedule: object providing sigma_rot(t)

Returns:

noisy_rotations: [..., 3, 3]

noise_rotations: [..., 3, 3] the IGSO(3) samples that were applied

"""

sigma = noise_schedule.sigma_rot(t)

# Sample noise rotation from IGSO(3)

noise_rot = sample_igso3(rotations.shape[:-2], sigma, rotations.device)

# Compose: R_t = R_noise @ R_0

noisy_rotations = torch.einsum('...ij,...jk->...ik', noise_rot, rotations)

return noisy_rotations, noise_rot

The Noise Schedule

The noise schedule controls how quickly the signal is destroyed during the forward process. RFDiffusion uses a cosine schedule for translations (which produces a smooth transition from clean to noisy) and a linear schedule for rotations:

class SE3DiffusionSchedule:

"""

Noise schedule for SE(3) diffusion on protein frames.

The translation schedule uses the cosine form from Nichol & Dhariwal (2021),

which avoids the abrupt noise increase at the end of a linear schedule.

The rotation schedule is linear in the IGSO(3) concentration parameter.

"""

def __init__(self, T=1000, trans_sigma_max=10.0, rot_sigma_max=1.5):

"""

Args:

T: number of diffusion timesteps

trans_sigma_max: maximum translation noise (Angstroms)

rot_sigma_max: maximum rotation noise (radians, roughly)

"""

self.T = T

self.trans_sigma_max = trans_sigma_max

self.rot_sigma_max = rot_sigma_max

def alpha_bar(self, t):

"""Cosine schedule for translations: alpha_bar(t) in [0, 1]."""

s = 0.008 # small offset to prevent alpha_bar(0) = 1 exactly

f_t = torch.cos((t + s) / (1 + s) * np.pi / 2) ** 2

f_0 = np.cos(s / (1 + s) * np.pi / 2) ** 2

return f_t / f_0

def sigma_rot(self, t):

"""Linear schedule for rotations: sigma(t) = t * sigma_max."""

return t * self.rot_sigma_max

def sample_timestep(self, batch_size, device='cpu'):

"""Sample uniform random timesteps in [0, 1]."""

return torch.rand(batch_size, device=device)

Combining Both Components

The full forward process diffuses translations and rotations jointly:

def diffuse_frames(frames, t, schedule):

"""

Apply the SE(3) forward diffusion process to protein frames.

Each residue frame T_i = (R_i, t_i) is independently noised:

- Positions receive Gaussian noise in R^3

- Orientations receive IGSO(3) noise on SO(3)

Args:

frames: RigidTransform with L residue frames

t: [L] or scalar timestep

schedule: SE3DiffusionSchedule

Returns:

noisy_frames: RigidTransform (the noised structure)

noise: dict with 'trans' and 'rot' noise components

"""

noisy_trans, trans_noise = diffuse_translations(

frames.trans, t.unsqueeze(-1), schedule

)

noisy_rots, rot_noise = diffuse_rotations(

frames.rots, t, schedule

)

noisy_frames = RigidTransform(noisy_rots, noisy_trans)

noise = {'trans': trans_noise, 'rot': rot_noise}

return noisy_frames, noise

graph LR

subgraph "Forward Process (Adding Noise)"

T0["t=0\nClean Protein\n(folded backbone)"]

T1["t=0.3\nSlightly Noisy\n(positions jittered,\nframes tilted)"]

T2["t=0.7\nVery Noisy\n(structure dissolving)"]

T3["t=1.0\nPure Noise\n(random positions +\nuniform rotations)"]

end

T0 -->|"+Gaussian\n+IGSO(3)"| T1 -->|"+noise"| T2 -->|"+noise"| T3

subgraph "Reverse Process (Denoising)"

R3["t=1.0\nRandom Frames"]

R2["t=0.7\nPartially\nDenoised"]

R1["t=0.3\nMostly\nDenoised"]

R0["t=0\nGenerated\nProtein"]

end

R3 -->|"neural net\npredicts clean"| R2 -->|"denoise"| R1 -->|"denoise"| R0

style T0 fill:#2ecc71,color:white

style T3 fill:#e74c3c,color:white

style R3 fill:#e74c3c,color:white

style R0 fill:#2ecc71,color:white

At \(t = 0\), the frames are clean. At \(t = 1\), the positions are nearly pure Gaussian noise and the orientations are nearly uniformly random. The neural network’s job is to learn the reverse of this process: given a noisy structure and the noise level, predict the clean structure.

7. Building Equivariant Neural Networks

The Core Principle

We need a neural network that takes noisy protein frames and produces denoised frames, while satisfying SE(3) equivariance. The design principle is:

Compute using invariant features. Apply results in local coordinate frames.

Invariant features are quantities that do not change when the entire protein is rotated or translated. Examples include distances between \(\text{C}_\alpha\) atoms, angles between bonds, and the relative rotation angle between two residue frames. These features are “safe” inputs to any standard neural network layer (MLPs, attention, etc.) because they carry no orientation information.

The outputs of the network — frame updates — are predicted in each residue’s local coordinate frame and then transformed to global coordinates using the residue’s rotation matrix. Because the local frame rotates with the protein, the global output rotates correctly.

Invariant Edge Features

The first step is to compute invariant features for each pair of interacting residues:

def compute_invariant_edge_features(frames, edge_index, max_dist=20.0):

"""

Compute SE(3)-invariant features for pairs of residues.

These features describe the geometric relationship between two

residues without reference to any global coordinate system.

Args:

frames: RigidTransform [N] (one frame per residue)

edge_index: [2, E] pairs of interacting residues

max_dist: maximum distance for radial basis encoding (Angstroms)

Returns:

edge_features: [E, edge_dim] invariant features

"""

src, dst = edge_index

# --- Distance (invariant under all of SE(3)) ---

pos_src = frames.trans[src]

pos_dst = frames.trans[dst]

distances = (pos_src - pos_dst).norm(dim=-1, keepdim=True)

# Encode distance with radial basis functions

rbf_dist = rbf_encode(distances, n_bins=16, max_val=max_dist)

# --- Relative rotation angle (invariant under global rotation) ---

# R_rel = R_dst^T @ R_src captures how one frame is rotated

# relative to the other, independent of global orientation.

R_rel = torch.einsum(

'eij,ejk->eik',

frames.rots[dst].transpose(-1, -2),

frames.rots[src]

)

trace = R_rel[:, 0, 0] + R_rel[:, 1, 1] + R_rel[:, 2, 2]

rot_angle = torch.acos(torch.clamp((trace - 1) / 2, -1, 1))

# Combine into feature vector

edge_features = torch.cat([

rbf_dist,

rot_angle.unsqueeze(-1),

torch.sin(rot_angle).unsqueeze(-1),

torch.cos(rot_angle).unsqueeze(-1)

], dim=-1)

return edge_features

def rbf_encode(distances, n_bins=16, max_val=20.0):

"""

Radial basis function encoding of distances.

Transforms a scalar distance into a vector of Gaussian bumps centered

at evenly spaced values. This gives the network a richer representation

of distance than a single scalar.

Args:

distances: [..., 1] pairwise distances in Angstroms

n_bins: number of Gaussian basis functions

max_val: maximum distance to encode

Returns:

rbf: [..., n_bins] encoded distances

"""

centers = torch.linspace(0, max_val, n_bins, device=distances.device)

gamma = 1.0 / (max_val / n_bins)

return torch.exp(-gamma * (distances - centers) ** 2)

The relative rotation angle \(\omega_{ij}\) between residues \(i\) and \(j\) is computed from the trace of the relative rotation matrix \(R_j^T R_i\). The trace of a rotation matrix is \(1 + 2\cos\omega\), so \(\omega = \arccos\!\bigl(\frac{\text{tr}(R_j^T R_i) - 1}{2}\bigr)\). This angle is invariant: rotating the entire protein changes both \(R_i\) and \(R_j\) by the same global rotation, which cancels in the product \(R_j^T R_i\).

An Equivariant Convolution Layer

With invariant edge features in hand, we can build a message-passing layer that updates both node features and positions equivariantly:

class SE3EquivariantConv(nn.Module):

"""

SE(3)-equivariant graph convolution layer for protein residues.

Messages between residues are computed from invariant features

(distances, relative orientations). Position updates are predicted

in the local coordinate frame of each source residue, then

transformed to global coordinates. This ensures equivariance:

rotating the input rotates the output by the same amount.

"""

def __init__(self, node_dim, edge_dim, hidden_dim=128):

super().__init__()

self.node_dim = node_dim

self.edge_dim = edge_dim

# Process invariant edge features

self.edge_mlp = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(edge_dim, hidden_dim),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(hidden_dim, hidden_dim)

)

# Compute scalar messages (invariant)

self.message_mlp = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(node_dim * 2 + hidden_dim, hidden_dim),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(hidden_dim, node_dim)

)

# Predict position displacements in local frames (equivariant)

self.pos_mlp = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(node_dim * 2 + hidden_dim, hidden_dim),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(hidden_dim, 3)

)

def forward(self, node_features, frames, edge_index, edge_features):

"""

Args:

node_features: [N, node_dim] per-residue features

frames: RigidTransform [N] per-residue frames

edge_index: [2, E] edges (pairs of interacting residues)

edge_features: [E, edge_dim] invariant edge features

Returns:

updated_features: [N, node_dim] updated per-residue features

position_updates: [N, 3] equivariant position updates

"""

src, dst = edge_index

N = node_features.shape[0]

# Embed edge features

edge_emb = self.edge_mlp(edge_features)

# Build message inputs

src_feat = node_features[src]

dst_feat = node_features[dst]

msg_input = torch.cat([src_feat, dst_feat, edge_emb], dim=-1)

# Compute scalar messages and aggregate

messages = self.message_mlp(msg_input)

agg = torch.zeros(N, self.node_dim, device=messages.device)

agg.scatter_add_(0, dst.unsqueeze(-1).expand(-1, self.node_dim), messages)

# Predict position updates in SOURCE residue's local frame

pos_local = self.pos_mlp(msg_input) # [E, 3]

# Transform to global coordinates using source frame's rotation

src_frames = RigidTransform(frames.rots[src], frames.trans[src])

pos_global = src_frames.apply(pos_local) - src_frames.trans

# Aggregate position updates at destination residues

pos_agg = torch.zeros(N, 3, device=pos_global.device)

pos_agg.scatter_add_(0, dst.unsqueeze(-1).expand(-1, 3), pos_global)

return node_features + agg, pos_agg

The equivariance guarantee comes from the position update pathway. The MLP pos_mlp receives only invariant inputs and produces a 3D vector in the local coordinate frame of the source residue. When the entire protein is rotated by \(R_g\), the source frame’s rotation becomes \(R_g R_i\), and the global update becomes \(R_g R_i \vec{d} = R_g (R_i \vec{d})\) — the original global update rotated by \(R_g\). This is exactly the equivariance condition.

8. The RFDiffusion Architecture

From Structure Prediction to Structure Generation

RFDiffusion does not build its neural network from scratch. Instead, it adapts the architecture of RoseTTAFold (missing reference), a protein structure prediction model, for the generative task. This strategy has two advantages: the pretrained weights provide a strong initialization, and the architecture is already designed to process protein geometry.

The high-level flow is:

- Input: noisy frames \(\{T_i^{(t)}\}\) plus conditioning information (motif positions, target structure, etc.) and the timestep \(t\).

- Processing: a stack of SE(3)-equivariant transformer blocks that jointly update per-residue features, pairwise features, and frames.

- Output: predicted clean frames \(\{T_i^{(0)}\}\).

A Single RFDiffusion Block

Each block in the stack performs three operations:

class RFDiffusionBlock(nn.Module):

"""

One block of the RFDiffusion denoising network.

Each block updates three representations:

1. Per-residue (node) features via Invariant Point Attention

2. Pairwise features via triangular updates

3. Residue frames via predicted rotational and translational updates

"""

def __init__(self, node_dim=256, pair_dim=128, n_heads=8):

super().__init__()

# Invariant Point Attention (from AlphaFold2's structure module)

self.node_attn = InvariantPointAttention(node_dim, pair_dim, n_heads)

# Triangular update on pair features (geometric consistency)

self.pair_update = TriangularUpdate(pair_dim)

# Frame update layer (predicts rotation + translation corrections)

self.frame_update = FrameUpdateLayer(node_dim)

# Timestep conditioning

self.time_embed = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(256, node_dim),

nn.SiLU(),

nn.Linear(node_dim, node_dim)

)

def forward(self, node_features, pair_features, frames, t_embed):

"""

Args:

node_features: [L, node_dim] per-residue features

pair_features: [L, L, pair_dim] pairwise relationship features

frames: RigidTransform [L] current residue frames

t_embed: [256] sinusoidal timestep embedding

Returns:

Updated node_features, pair_features, and frames

"""

# Inject timestep information into node features

time_bias = self.time_embed(t_embed)

node_features = node_features + time_bias.unsqueeze(0)

# Update node features using Invariant Point Attention

node_features = self.node_attn(node_features, pair_features, frames)

# Update pair features with triangular consistency

pair_features = self.pair_update(pair_features)

# Predict and apply frame updates

frame_updates = self.frame_update(node_features)

frames = update_frames(frames, frame_updates)

return node_features, pair_features, frames

The three components work together:

Invariant Point Attention (IPA) is the attention mechanism from AlphaFold2’s structure module (Lecture 4). It computes attention weights using both the learned features and the geometric relationship between residue frames. The attention is SE(3)-invariant: rotating the protein does not change which residues attend to which.

Triangular updates enforce geometric consistency in the pairwise features. If residue A is close to B, and B is close to C, then the A-C relationship should reflect this transitivity. These updates propagate geometric constraints through the pair representation.

Frame updates are the final layer that predicts how to adjust each residue’s position and orientation.

Predicting Frame Updates

The frame update layer outputs small corrections in axis-angle format for rotations and Cartesian coordinates for translations:

class FrameUpdateLayer(nn.Module):

"""

Predict per-residue frame corrections (rotation + translation).

The rotation update is predicted as an axis-angle vector (3D),

converted to a rotation matrix, and composed with the current frame.

The translation update is a 3D displacement added to the current position.

"""

def __init__(self, node_dim):

super().__init__()

self.norm = nn.LayerNorm(node_dim)

self.to_update = nn.Linear(node_dim, 6) # 3 rotation + 3 translation

self.rot_scale = 0.1 # keep rotation updates small

self.trans_scale = 1.0 # translation updates in Angstroms

def forward(self, node_features):

"""

Args:

node_features: [L, node_dim] per-residue features

Returns:

dict with 'rot' ([L, 3] axis-angle) and 'trans' ([L, 3]) updates

"""

x = self.norm(node_features)

updates = self.to_update(x)

rot_update = updates[:, :3] * self.rot_scale

trans_update = updates[:, 3:] * self.trans_scale

return {'rot': rot_update, 'trans': trans_update}

def update_frames(frames, updates):

"""

Apply predicted updates to residue frames by composition.

The update is treated as a small rigid-body transformation that is

composed (not added) with the current frame. This respects the

group structure of SE(3).

"""

rot_update = axis_angle_to_rotation_matrix(updates['rot'])

trans_update = updates['trans']

update_transform = RigidTransform(rot_update, trans_update)

# Compose: T_new = T_current o T_update

return frames.compose(update_transform)

The scale factors rot_scale = 0.1 and trans_scale = 1.0 are important for training stability. Without them, the initial random weights would produce large, erratic frame updates that destabilize the optimization. Scaling down the rotation updates is especially important because even small angles produce significant structural changes when applied to many residues simultaneously.

9. Conditional Generation: Where the Magic Happens

From Random Backbones to Designed Proteins

Generating random protein backbones is a technical achievement, but the practical value of RFDiffusion lies in conditional generation: producing proteins that satisfy specific design objectives. Four conditioning strategies cover the most important use cases.

Motif scaffolding. A functional motif — say, a set of catalytic residues arranged in a specific geometry — must be presented by a supporting protein scaffold. RFDiffusion generates the scaffold while holding the motif residues fixed.

graph LR

subgraph "Input"

M["Functional Motif\n(fixed geometry,\ne.g. catalytic triad)"]

end

subgraph "Diffusion Process"

N["Random Scaffold\nFrames (noise)"]

D1["Denoise Step 1:\nClamp motif,\nupdate scaffold"]

D2["Denoise Step 2:\nClamp motif,\nupdate scaffold"]

DN["... N steps ..."]

end

subgraph "Output"

P["Complete Protein:\nMotif + Generated\nScaffold"]

end

M --> D1

N --> D1 --> D2 --> DN --> P

style M fill:#e74c3c,color:white

style N fill:#95a5a6,color:white

style P fill:#2ecc71,color:white

style D1 fill:#f39c12,color:white

style D2 fill:#f39c12,color:white

Binder design. Given a target protein (for example, a viral surface protein), design a new protein that binds to a specified surface region on the target. This is the key to computational vaccine and therapeutic design.

Symmetric assemblies. Generate proteins with specified symmetry — dimers (\(C_2\)), trimers (\(C_3\)), or higher-order assemblies — that can form cages, rings, or filaments.

Secondary structure conditioning. Specify a desired pattern of helices and sheets, and let the model determine the three-dimensional arrangement.

Motif Conditioning in Practice

The simplest and most effective conditioning strategy is inpainting: at each step of the reverse diffusion process, replace the frames at motif positions with the ground-truth values. The model generates the remaining (scaffold) residues conditioned on the fixed motif geometry.

class MotifConditioning:

"""

Condition the diffusion process on a fixed structural motif.

During each denoising step, motif residue frames are clamped to their

ground-truth values. The model learns to generate scaffold residues

that are geometrically compatible with the fixed motif.

"""

def __init__(self, motif_positions, motif_frames):

"""

Args:

motif_positions: list of int, residue indices to hold fixed

motif_frames: RigidTransform for the motif residues

"""

self.motif_pos = set(motif_positions)

self.motif_frames = motif_frames

def apply(self, frames, t):

"""

Replace motif positions with ground-truth frames.

Called at each denoising step to enforce the motif constraint.

"""

for i, pos in enumerate(self.motif_pos):

frames.rots[pos] = self.motif_frames.rots[i]

frames.trans[pos] = self.motif_frames.trans[i]

return frames

def get_conditioning_mask(self, L):

"""

Return a binary mask: 1 for motif (fixed), 0 for scaffold (generated).

"""

mask = torch.zeros(L)

for pos in self.motif_pos:

mask[pos] = 1

return mask

This approach is effective because the denoising network has learned, from thousands of training structures, what kinds of scaffolds are geometrically and energetically plausible. Clamping the motif constrains the solution space to scaffolds that are compatible with the desired functional geometry.

Self-Conditioning

Self-conditioning feeds the model’s own previous prediction back as additional input (missing reference). During training, with probability 0.5, the model first makes a prediction without self-conditioning, then makes a second prediction that also receives the first prediction as input. Only the second prediction is used to compute the loss.

class SelfConditionedRFDiffusion(nn.Module):

"""

RFDiffusion with self-conditioning.

At each denoising step, the model can optionally receive its own

previous prediction as input. This helps maintain consistency

across steps and improves sample quality.

"""

def __init__(self, base_model):

super().__init__()

self.base_model = base_model

# Project 7D frame representation (4 quat + 3 trans) to features

self.self_cond_proj = nn.Linear(7, 128)

def forward(self, noisy_frames, t, prev_pred=None):

if prev_pred is not None:

self_cond = self.self_cond_proj(prev_pred.to_tensor_7())

else:

self_cond = torch.zeros(noisy_frames.trans.shape[0], 128)

return self.base_model(noisy_frames, t, self_cond)

Self-conditioning provides the model with a “rough draft” of the final structure, allowing it to make more coherent updates. Without self-conditioning, each denoising step must independently infer global structural context from the noisy input alone.

Classifier-Free Guidance

Classifier-free guidance (missing reference) provides a continuous knob to control the strength of conditioning. During training, the conditioning signal is randomly dropped (replaced with zeros) with some probability. At inference time, the model is run twice — once with conditioning and once without — and the predictions are combined:

\[\hat{x}_0^{\text{guided}} = \hat{x}_0^{\text{uncond}} + s \cdot (\hat{x}_0^{\text{cond}} - \hat{x}_0^{\text{uncond}}),\]where \(s\) is the guidance scale. When \(s = 1\), this reduces to the conditional prediction. When \(s > 1\), the model extrapolates beyond the conditional prediction, producing structures that satisfy the constraints more strongly at the cost of reduced diversity.

def sample_with_guidance(model, initial_frames, condition,

guidance_scale=2.0, steps=100):

"""

Generate a protein backbone with classifier-free guidance.

Higher guidance_scale produces structures that more strongly

satisfy the conditioning constraints, but with less diversity.

Args:

model: trained RFDiffusion model

initial_frames: starting frames (typically random noise)

condition: conditioning information (motif, target, etc.)

guidance_scale: s > 1 for stronger conditioning

steps: number of denoising steps

"""

frames = initial_frames

schedule = SE3DiffusionSchedule()

for step in range(steps, 0, -1):

t = torch.tensor([step / steps])

# Conditional prediction (with design constraints)

pred_cond = model(frames, t, condition)

# Unconditional prediction (no constraints)

pred_uncond = model(frames, t, None)

# Guided prediction: extrapolate in the conditioning direction

pred = pred_uncond + guidance_scale * (pred_cond - pred_uncond)

# Take one denoising step

frames = denoise_step(frames, pred, t, schedule)

return frames

In practice, guidance scales between 1.0 and 3.0 work well for protein design. Too high a guidance scale can produce structures with strained geometry.

10. Training the Model

The Loss Function

The training objective is straightforward: given a noisy protein structure and the noise level, predict the clean structure. The loss is computed separately for translations and rotations, using the appropriate metric for each space.

For translations, the loss is the standard mean squared error in Euclidean space:

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{trans}} = \frac{1}{L} \sum_{i=1}^{L} \lVert \hat{\vec{t}}_i - \vec{t}_i \rVert^2,\]where \(\hat{\vec{t}}_i\) is the predicted \(\text{C}_\alpha\) position and \(\vec{t}_i\) is the ground truth.

For rotations, the loss is the squared geodesic distance on \(SO(3)\):

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{rot}} = \frac{1}{L} \sum_{i=1}^{L} \omega_i^2,\]where \(\omega_i = \arccos\!\left(\frac{\text{tr}(\hat{R}_i^T R_i) - 1}{2}\right)\) is the angle of the relative rotation between the predicted and true orientations. The geodesic distance is the natural metric on \(SO(3)\): it measures the shortest arc between two rotations on the rotation manifold7.

The total loss is a weighted sum:

\[\mathcal{L} = \lambda_{\text{trans}} \mathcal{L}_{\text{trans}} + \lambda_{\text{rot}} \mathcal{L}_{\text{rot}}.\]def rfdiffusion_loss(pred_frames, true_frames, t, loss_weights=None):

"""

Compute the RFDiffusion training loss.

The loss has two components:

- Translation loss: MSE in Euclidean space (Angstroms^2)

- Rotation loss: squared geodesic distance on SO(3) (radians^2)

Args:

pred_frames: RigidTransform, model predictions

true_frames: RigidTransform, ground truth from PDB

t: timestep (for potential weighting)

loss_weights: dict with 'trans' and 'rot' weights

Returns:

total_loss: scalar

losses: dict with individual loss components

"""

losses = {}

# --- Translation loss: L2 distance between C-alpha positions ---

trans_loss = (

(pred_frames.trans - true_frames.trans) ** 2

).sum(dim=-1).mean()

losses['trans'] = trans_loss

# --- Rotation loss: geodesic distance on SO(3) ---

# R_diff = R_pred @ R_true^T gives the relative rotation

R_diff = torch.einsum(

'...ij,...kj->...ik',

pred_frames.rots,

true_frames.rots

)

trace = R_diff[:, 0, 0] + R_diff[:, 1, 1] + R_diff[:, 2, 2]

rot_angle = torch.acos(

torch.clamp((trace - 1) / 2, -1 + 1e-7, 1 - 1e-7)

)

rot_loss = (rot_angle ** 2).mean()

losses['rot'] = rot_loss

# --- Combine ---

if loss_weights is None:

loss_weights = {'trans': 1.0, 'rot': 1.0}

total_loss = sum(

loss_weights.get(k, 1.0) * v for k, v in losses.items()

)

return total_loss, losses

The Training Loop

A single training step samples a random timestep, noises the ground-truth structure, and trains the model to recover it:

def training_step(model, batch, optimizer, schedule):

"""

One step of RFDiffusion training.

1. Sample a random noise level t

2. Add noise to the ground-truth protein structure

3. Feed the noisy structure to the model

4. Compute loss between prediction and ground truth

5. Update model weights

"""

true_frames = batch['frames'] # Ground truth from PDB

L = true_frames.trans.shape[0] # Number of residues

# Sample a random timestep uniformly in [0, 1]

t = schedule.sample_timestep(1).expand(L)

# Apply the forward diffusion process

noisy_frames, noise = diffuse_frames(true_frames, t, schedule)

# Model predicts the clean structure from the noisy input

pred_frames = model(noisy_frames, t)

# Compute and minimize the loss

loss, loss_dict = rfdiffusion_loss(pred_frames, true_frames, t)

optimizer.zero_grad()

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

return loss_dict

RFDiffusion is trained on structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), using a curated set of high-quality single-chain and multi-chain structures. Training takes several days on a cluster of GPUs. The pretrained RoseTTAFold weights provide a strong initialization that significantly accelerates convergence.

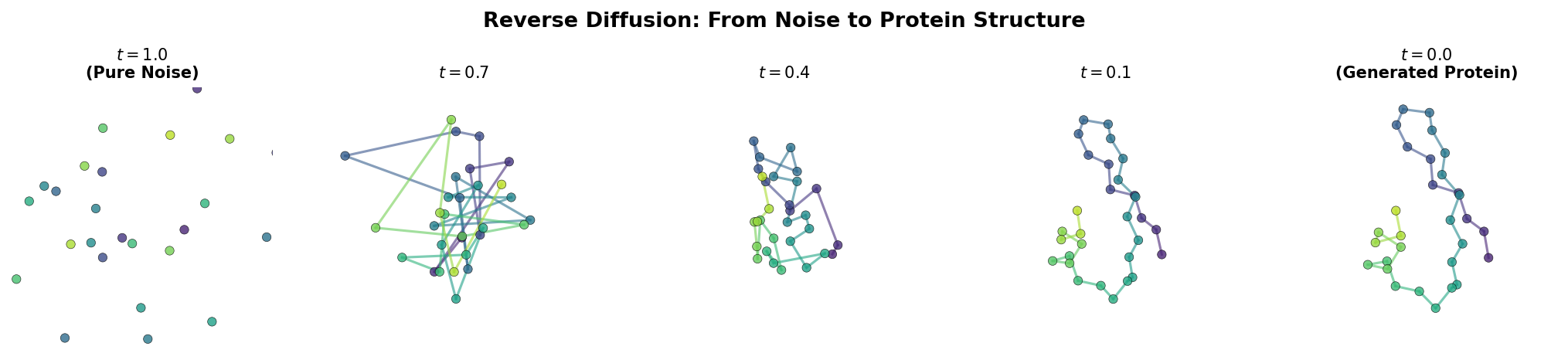

11. Generating New Proteins

The Reverse Process

Generation is the reverse of training: start from pure noise and iteratively denoise to produce a coherent protein backbone. Each step involves three operations:

- The model predicts the clean structure from the current noisy state.

- The prediction is used to compute the denoised estimate at the next (less noisy) timestep.

- Any conditioning constraints are applied (e.g., fixing motif positions).

@torch.no_grad()

def sample_rfdiffusion(model, L, schedule, n_steps=100, condition=None):

"""

Generate a novel protein backbone using RFDiffusion.

Starting from random noise, iteratively denoise to produce a

coherent protein backbone with L residues.

Args:

model: trained RFDiffusion model

L: desired number of residues

schedule: SE3DiffusionSchedule

n_steps: number of denoising steps (more steps = higher quality)

condition: optional conditioning (MotifConditioning, etc.)

Returns:

frames: RigidTransform with the generated backbone

"""

# Initialize: identity frames + maximum noise = random structure

frames = RigidTransform.identity((L,), device='cuda')

t_max = torch.ones(L, device='cuda')

frames, _ = diffuse_frames(frames, t_max, schedule)

# Self-conditioning state

prev_pred = None

# Denoise from t=1 (pure noise) to t=0 (clean structure)

timesteps = torch.linspace(1, 0, n_steps + 1)

for i in range(n_steps):

t_now = timesteps[i]

t_next = timesteps[i + 1]

t_tensor = torch.full((L,), t_now, device='cuda')

# Model predicts the clean structure

pred_frames = model(frames, t_tensor, condition, prev_pred)

# Self-conditioning: with 50% probability, feed prediction

# back to the model at the next step

if torch.rand(1) < 0.5:

prev_pred = pred_frames

# Move one step closer to the clean structure

if t_next > 0:

frames = denoise_and_renoise(

frames, pred_frames, t_now, t_next, schedule

)

else:

# Final step: use the prediction directly

frames = pred_frames

# Enforce conditioning constraints

if condition is not None:

frames = condition.apply(frames, t_next)

return frames

The Denoising Step on SE(3)

The denoising update must respect the different geometries of translations and rotations:

def denoise_and_renoise(noisy_frames, pred_clean, t_now, t_next, schedule):

"""

Take one denoising step from t_now to t_next on SE(3).

For translations: use the standard DDPM update rule in R^3.

For rotations: interpolate on SO(3) toward the predicted clean rotation.

Args:

noisy_frames: current noisy frames at timestep t_now

pred_clean: model's prediction of the clean frames

t_now: current timestep

t_next: target timestep (t_next < t_now)

schedule: SE3DiffusionSchedule

"""

# --- Translations: DDPM update in R^3 ---

alpha_now = schedule.alpha_bar(torch.tensor(t_now))

alpha_next = schedule.alpha_bar(torch.tensor(t_next))

# Estimate the noise that was added

noise_est = (

(noisy_frames.trans - torch.sqrt(alpha_now) * pred_clean.trans)

/ torch.sqrt(1 - alpha_now)

)

# Posterior mean at t_next

trans_mean = (

torch.sqrt(alpha_next) * pred_clean.trans

+ torch.sqrt(1 - alpha_next) * noise_est

)

# Add stochastic noise (except at the final step)

if t_next > 0:

noise = torch.randn_like(trans_mean)

beta = 1 - alpha_next / alpha_now

trans_next = trans_mean + torch.sqrt(beta) * noise

else:

trans_next = trans_mean

# --- Rotations: interpolate on SO(3) via SLERP ---

sigma_now = schedule.sigma_rot(torch.tensor(t_now))

sigma_next = schedule.sigma_rot(torch.tensor(t_next))

# Interpolation factor: how far to move toward the clean rotation

interp_factor = sigma_next / (sigma_now + 1e-8)

rots_next = slerp_rotation(

noisy_frames.rots, pred_clean.rots, 1 - interp_factor

)

return RigidTransform(rots_next, trans_next)

For translations, the update follows the standard DDPM formula from Ho et al. (2020): estimate the noise, compute the posterior mean, and add scaled noise. For rotations, we use spherical linear interpolation (SLERP) between the current noisy rotation and the predicted clean rotation8. The interpolation factor is determined by the ratio of noise levels: at each step, we move fractionally closer to the predicted clean orientation.

12. Experimental Validation and Comparison

Proteins That Actually Work

The ultimate test of any protein design method is experimental validation. RFDiffusion has been validated extensively, with several categories of results reported in the original Nature paper (missing reference):

Novel folds. RFDiffusion generates backbone topologies never observed in nature. When the corresponding amino acid sequences were designed (using ProteinMPNN (missing reference)), synthesized, and expressed in E. coli, the proteins folded into the predicted structures. Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and circular dichroism (CD) measurements confirmed the expected size, shape, and secondary structure content.

Symmetric assemblies. By incorporating symmetry constraints (e.g., \(C_3\) for trimers or octahedral symmetry for cages), RFDiffusion designs proteins that self-assemble into multi-subunit architectures. Cryo-electron microscopy confirmed the designed symmetry.

Functional binders. RFDiffusion has designed proteins that bind to therapeutically relevant targets — including influenza hemagglutinin and SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain — with nanomolar affinity. This demonstrates the practical potential for drug and vaccine development.

Enzyme scaffolds. By scaffolding around known catalytic motifs (fixing the positions of key catalytic residues), researchers have generated novel enzyme backbones. The model produces scaffolds that hold the catalytic residues in the correct geometry, enabling enzymatic activity.

Comparison with Other Methods

Several groups have developed alternative approaches to protein backbone generation. The following table summarizes the key differences:

| Method | Representation | Symmetry | Generation Approach | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFDiffusion | SE(3) frames | SE(3) equivariant | Diffusion (DDPM) | Pretrained from RoseTTAFold; rich conditioning |

| Chroma | Distance matrix | E(3) invariant | Diffusion | Simpler representation; scalable |

| FrameDiff | SE(3) frames | SE(3) equivariant | Flow matching | Theoretically principled; continuous-time |

| Genie | Backbone angles | None | Autoregressive | Simple; no equivariance overhead |

RFDiffusion’s strength is the combination of SE(3) equivariance, the powerful pretrained RoseTTAFold backbone, and the flexible conditioning mechanisms that enable practical design applications. Chroma trades some geometric expressiveness for a simpler, distance-matrix-based representation. FrameDiff uses the same SE(3) frame representation but replaces the diffusion process with flow matching, which offers cleaner training dynamics. Genie takes the simplest approach, generating backbone angles autoregressively without explicit geometric symmetry.

The field is evolving rapidly, and each method has its niche. But RFDiffusion’s experimental success has established SE(3) diffusion as a dominant paradigm for structure-based protein design.

13. Key Takeaways

-

Proteins are geometric objects. Their biological properties depend on three-dimensional shape, not on how that shape is oriented in a coordinate system. This makes SE(3) equivariance a natural requirement for protein generative models.

-

Each residue defines a coordinate frame. The frame representation — treating each amino acid as a rigid-body transformation \((R_i, \vec{t}_i) \in SE(3)\) — captures the full backbone geometry in a compact and geometrically natural way.

-

Rotations require non-Euclidean noise. Standard Gaussian diffusion cannot be applied directly to rotations because \(SO(3)\) is a curved manifold. The IGSO(3) distribution provides a principled analogue: isotropic noise that smoothly interpolates between the identity and the uniform distribution over rotations.

-

Equivariance is built into the architecture. By computing with invariant features (distances, relative rotation angles) and applying updates in local coordinate frames, the neural network respects SE(3) symmetry exactly, without data augmentation.

-

Conditional generation enables practical design. Motif scaffolding, binder design, and symmetric assembly generation all work by constraining the diffusion process during inference. Classifier-free guidance provides fine control over the conditioning strength.

-

Experimental validation confirms the approach. RFDiffusion-designed proteins fold as predicted and perform intended functions, representing a qualitative advance in computational protein design.

14. Exercises

Conceptual Questions

Exercise 1: Equivariance vs. Invariance. Suppose you have a protein scoring function \(E(T_1, \ldots, T_L) \in \mathbb{R}\) that assigns an energy to a protein backbone. Should this function be SE(3)-invariant or SE(3)-equivariant? What about a denoising function \(f(T_1, \ldots, T_L) = (T_1', \ldots, T_L')\) that maps noisy frames to clean frames? Explain your reasoning.

Exercise 2: Degrees of Freedom. A protein backbone with \(L\) residues is represented by \(L\) frames in \(SE(3)\). How many total degrees of freedom does this representation have? Compare this to representing the same backbone as \(3L\) atom positions (N, \(\text{C}_\alpha\), C for each residue). Which representation has more parameters? Which has more intrinsic degrees of freedom?

Exercise 3: Why Quaternions? RFDiffusion uses quaternions internally rather than rotation matrices or Euler angles. Give two concrete numerical scenarios where quaternions would outperform Euler angles (hint: think about gimbal lock and interpolation).

Mathematical Problems

Exercise 4: Rotation Composition. Let \(R_1\) be a rotation by \(90°\) about the \(z\)-axis and \(R_2\) be a rotation by \(90°\) about the \(x\)-axis. Compute \(R_1 R_2\) and \(R_2 R_1\). Are they the same? What does this tell you about the group structure of \(SO(3)\)?

Exercise 5: Geodesic Distance. The geodesic distance between two rotations \(R_1\) and \(R_2\) on \(SO(3)\) is the angle \(\omega\) of the relative rotation \(R_1^T R_2\). Show that \(\omega = \arccos\!\left(\frac{\text{tr}(R_1^T R_2) - 1}{2}\right)\). (Hint: use the fact that \(\text{tr}(R) = 1 + 2\cos\omega\) for a rotation by angle \(\omega\).)

Exercise 6: IGSO(3) Limiting Behavior. Argue informally that as \(\sigma \to 0\), samples from IGSO(3) with parameter \(\sigma\) converge to the identity rotation. As \(\sigma \to \infty\), what distribution do the samples approach? Why is this property essential for a diffusion process?

Implementation Challenges

Exercise 7: Rodrigues Formula. Implement the function axis_angle_to_rotation_matrix and verify that it satisfies the following properties: (a) \(R(\hat{n}, 0) = I\) for any axis \(\hat{n}\). (b) \(R(\hat{n}, 2\pi) = I\) for any axis \(\hat{n}\). (c) \(R(\hat{n}, \omega)^T = R(\hat{n}, -\omega)\). Write unit tests for each property.

Exercise 8: Frame Composition. Using the RigidTransform class, verify that composition is associative: \((T_1 \circ T_2) \circ T_3 = T_1 \circ (T_2 \circ T_3)\) for random frames \(T_1, T_2, T_3\). Also verify that composition with the inverse yields the identity: \(T \circ T^{-1} = I\).

Exercise 9: Invariant Features. The function compute_invariant_edge_features computes distances and relative rotation angles. Verify numerically that these features are indeed invariant: apply a random SE(3) transformation to all frames and confirm that the computed features do not change (up to floating-point tolerance).

Exercise 10: Mini Diffusion. Implement a simplified one-dimensional diffusion process on \(SO(2)\) (rotations in the plane, parameterized by a single angle \(\theta \in [0, 2\pi)\)). Define a forward process that adds wrapped Gaussian noise, a simple MLP denoiser, and a reverse process. Train on a dataset of angles drawn from a mixture of von Mises distributions. Does the model learn to generate samples from the training distribution?

References

-

Watson, J. L., Juergens, D., Bennett, N. R., Trippe, B. L., Yim, J., Eisenach, H. E., … & Baker, D. (2023). De novo design of protein structure and function with RFdiffusion. Nature, 620(7976), 1089–1100.

-

Yim, J., Trippe, B. L., De Bortoli, V., Mathieu, E., Doucet, A., Barzilay, R., & Jaakkola, T. (2023). SE(3) diffusion model with application to protein backbone generation. Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML).

-

Leach, A., Schmon, S. M., Sherrill-Mix, S., & Wood, F. (2022). Denoising diffusion probabilistic models on SO(3) for rotational alignment. ICLR 2022 Workshop on Geometrical and Topological Representation Learning.

-

Baek, M., DiMaio, F., Anishchenko, I., Dauparas, J., Ovchinnikov, S., Lee, G. R., … & Baker, D. (2021). Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network. Science, 373(6557), 871–876.

-

Dauparas, J., Anishchenko, I., Bennett, N., Bai, H., Ragotte, R. J., Milles, L. F., … & Baker, D. (2022). Robust deep learning–based protein sequence design using ProteinMPNN. Science, 378(6615), 49–56.

-

Ho, J., Jain, A., & Abbeel, P. (2020). Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 33, 6840–6851.

-

Ho, J., & Salimans, T. (2022). Classifier-free diffusion guidance. NeurIPS 2021 Workshop on Deep Generative Models and Downstream Applications.

-

Jumper, J., Evans, R., Pritzel, A., Green, T., Figurnov, M., Ronneberger, O., … & Hassabis, D. (2021). Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature, 596(7873), 583–589.

-

Nichol, A. Q., & Dhariwal, P. (2021). Improved denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML).

-

Shoemake, K. (1985). Animating rotation with quaternion curves. ACM SIGGRAPH Computer Graphics, 19(3), 245–254.

-

The “S” stands for “special,” meaning the determinant of the rotation matrix is \(+1\) (no reflections). The “E” stands for “Euclidean.” The “3” is the spatial dimension. ↩

-

\(SO(3)\) stands for the Special Orthogonal group in three dimensions. “Orthogonal” refers to the constraint \(R^T R = I\); “special” means \(\det(R) = +1\). ↩

-

The Rodrigues formula is named after Olinde Rodrigues, who derived it in 1840. It provides the exponential map from the Lie algebra \(\mathfrak{so}(3)\) to the Lie group \(SO(3)\): specifically, \(R = \exp(\omega K)\). ↩

-

Strictly, the backbone is not perfectly rigid — bond angles and the peptide bond dihedral (\(\omega\)) have some flexibility. But the deviation from planarity is small enough that the rigid-body approximation is excellent for backbone generation. ↩

-

Some authors call this the “isotropic Gaussian on the rotation group” or the “angular central Gaussian.” The term IGSO(3) is standard in the protein diffusion literature following Leach et al. (2022) and Yim et al. (2023). ↩

-

The full density involves Wigner functions from the representation theory of \(SO(3)\). For implementation, the axis-angle sampling procedure described in the text is more practical than evaluating this series. ↩

-

On a curved manifold, the geodesic distance is the length of the shortest path between two points. On \(SO(3)\), this is the rotation angle needed to go from one orientation to the other. Using Euclidean distance between rotation matrices would be geometrically inappropriate and would weight large-angle errors incorrectly. ↩

-

SLERP (Spherical Linear Interpolation) was introduced by Ken Shoemake in 1985 for interpolating quaternions. It follows the shortest arc on \(SO(3)\) between two rotations, unlike linear interpolation of Euler angles which can produce non-physical trajectories. ↩