AlphaFold: Protein Structure Prediction

This post accompanies Lecture 4 of the Protein & Artificial Intelligence course (Spring 2026), co-taught by Prof. Sungsoo Ahn and Prof. Homin Kim at KAIST Graduate School of AI. It assumes familiarity with transformers and attention mechanisms (Lecture 2) as well as protein language models (Lecture 3). All code examples use PyTorch and are simplified for pedagogical clarity.

Introduction

In November 2020, DeepMind’s AlphaFold2 achieved what many structural biologists had considered a decades-away milestone: predicting protein structures from amino acid sequences at near-experimental accuracy. The result was not a lucky accident. AlphaFold2 encodes deep biological insight—about protein evolution, three-dimensional geometry, and physical symmetry—directly into its neural network architecture.

This lecture dissects the AlphaFold2 system from end to end. We begin with the historical context that defines why protein structure prediction is hard, then walk through every major component: input embedding, the Evoformer, the Structure Module, and the FAPE loss. Along the way we examine simplified PyTorch implementations of each piece, so that the architecture is not just conceptual but concrete.

Roadmap

| Section | Topic | Why It Is Needed |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Historical context | Frames the 50-year challenge and the CASP benchmark |

| 2 | Bird’s-eye view | Establishes the high-level data flow before details |

| 3 | Input embedding | Translates sequences and MSAs into tensor representations |

| 4 | Evoformer | Extracts co-evolutionary and geometric signals |

| 5 | Structure Module | Converts learned features into 3D atomic coordinates |

| 6 | FAPE loss | Defines what “correct structure” means for training |

| 7 | Full pipeline | Assembles the pieces into one coherent system |

| 8 | Design principles | Distills the recurring architectural ideas |

| 9 | Computational considerations | Addresses memory, speed, and scaling |

| 10 | Exercises | Practice problems for self-study |

1. Historical Context: The Fifty-Year Challenge

1.1 Anfinsen’s Thermodynamic Hypothesis

In 1972, Christian Anfinsen received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for demonstrating that a protein’s amino acid sequence contains all the information necessary to determine its three-dimensional structure1. His experiments on ribonuclease A showed that a denatured (unfolded) protein could spontaneously refold into its functional form once the denaturing agent was removed. The implication was clear: the sequence dictates the fold.

1.2 Levinthal’s Paradox

If sequence determines structure, why can we not simply compute the structure? Cyrus Levinthal pointed out a devastating combinatorial obstacle. A protein of just 100 amino acids, a small protein by any measure, can adopt an astronomical number of backbone conformations. If the protein sampled one trillion conformations per second, it would still take longer than the age of the universe to enumerate them all. Yet real proteins fold in milliseconds.

This is Levinthal’s paradox: the folding process must follow a guided search, not a random one. The energy landscape is “funneled,” steering the chain toward the native state through progressively lower-energy intermediates2. But knowing that a shortcut exists is different from knowing what it is.

1.3 CASP and the Structure Prediction Community

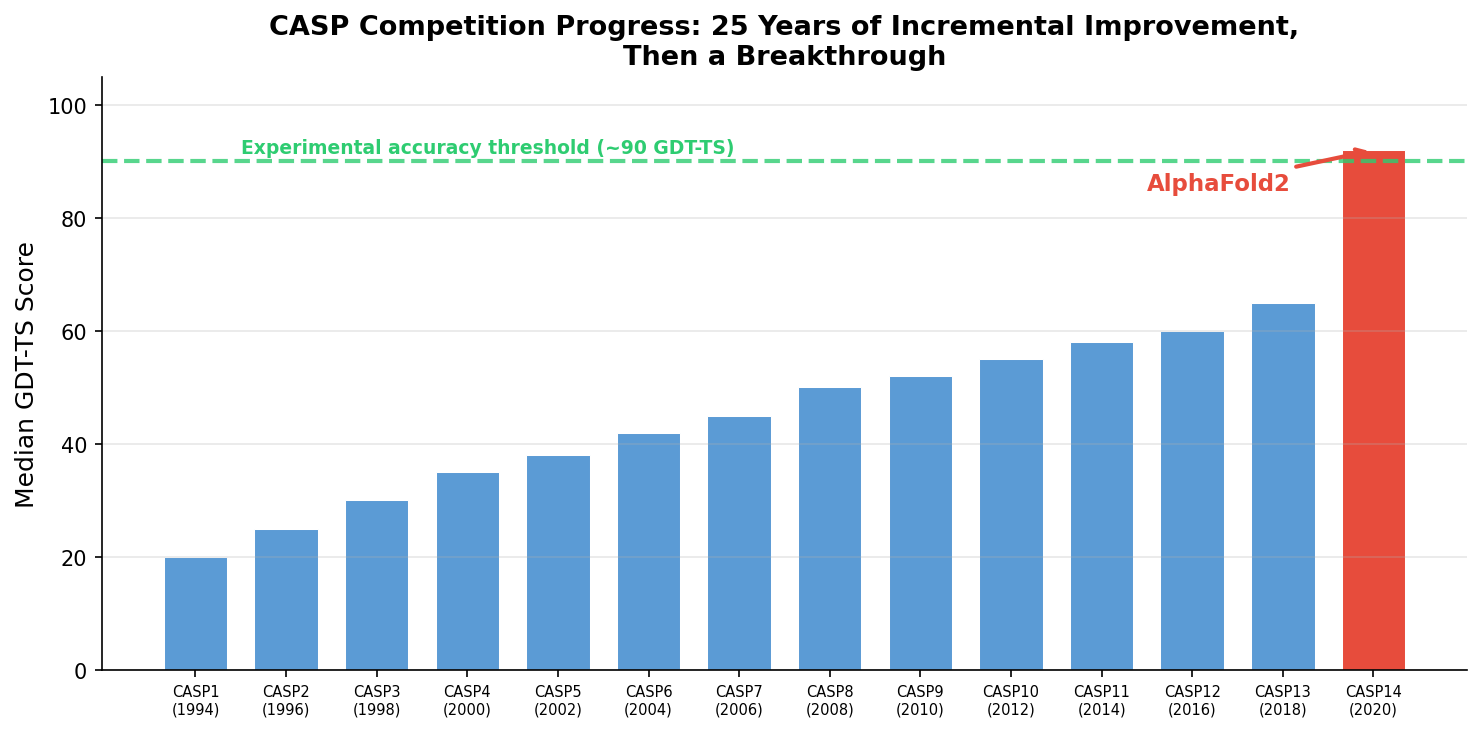

The Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) competition, launched in 1994, gave the field a rigorous benchmark. Every two years, organizers release protein sequences whose structures have been determined experimentally but not yet published. Prediction groups submit blind predictions, and the results are evaluated against the hidden ground truth.

For 25 years, progress was incremental. Methods improved from roughly 20 GDT-TS (a score where 100 means perfect) in early CASPs to the mid-60s by 2018. Then AlphaFold2 appeared at CASP14 in 2020 and scored a median GDT-TS above 90, crossing the threshold of experimental accuracy for most targets3. A problem that had resisted half a century of effort appeared to yield almost overnight to deep learning.

2. Bird’s-Eye View: How AlphaFold2 Thinks About Proteins

Before diving into equations and code, it helps to understand AlphaFold2’s overall strategy in plain language.

2.1 The Core Insight: No Protein Is Alone

When predicting a protein’s structure, one might think the only available information is the sequence itself—a string of amino acid letters. But every protein has evolutionary relatives: sequences that diverged from a common ancestor and have been independently shaped by natural selection.

These relatives are collected into a multiple sequence alignment (MSA), where homologous sequences are arranged so that evolutionarily equivalent positions line up in columns. Examining an MSA reveals two kinds of signal:

- Conservation. Some positions rarely change because mutations there would break the protein.

- Co-variation. Some positions change together: when position 15 mutates, position 47 compensates. These correlated mutations indicate that the two positions are in physical contact in the folded structure.

AlphaFold2 makes evolutionary information the central organizing principle of its architecture, not merely an input feature.

2.2 AlphaFold2 Pipeline Overview

The following diagram shows the overall architecture of AlphaFold2, from input sequences to 3D structure output.

flowchart TB

SEQ["Protein Sequence"] --> MSA_SEARCH["MSA Search\n(genetic databases)"]

SEQ --> TEMP["Template Search\n(PDB structures)"]

MSA_SEARCH --> MSA_EMB["MSA Embedding\n(N_seq × L × c_m)"]

TEMP --> PAIR_EMB["Pair Embedding\n(L × L × c_z)"]

SEQ --> PAIR_EMB

MSA_EMB --> EVO["Evoformer\n(48 blocks)"]

PAIR_EMB --> EVO

EVO -->|"MSA repr"| SM["Structure Module\n(8 recycling iterations)"]

EVO -->|"Pair repr"| SM

SM --> XYZ["3D Atomic\nCoordinates"]

SM --> CONF["Confidence\n(pLDDT)"]

style EVO fill:#fff3e0,stroke:#FF9800

style SM fill:#e8f5e9,stroke:#4CAF50

2.2 Two Representations, One Structure

AlphaFold2 maintains two parallel data structures throughout most of its computation:

- The MSA representation has shape \([N_{\text{seq}} \times L \times c_m]\), where \(N_{\text{seq}}\) is the number of aligned sequences, \(L\) is the protein length, and \(c_m\) is the feature dimension. Each entry encodes information about one position in one sequence.

- The pair representation has shape \([L \times L \times c_z]\). Entry \((i, j)\) encodes what the network believes about the relationship between residue \(i\) and residue \(j\)—their spatial proximity, hydrogen-bonding potential, or co-evolutionary coupling.

These two representations communicate throughout the network. Evolutionary signals from the MSA inform pairwise relationships, and pairwise constraints help interpret the MSA. By the end of this exchange, the pair representation contains a detailed predicted distance map.

2.3 From Distances to Coordinates

A distance map tells you which residues are close, but it does not directly specify where they are in three-dimensional space. The Structure Module takes the refined representations and converts them into atomic coordinates. This conversion must respect the symmetries of Euclidean space: rotating or translating a protein does not change its internal structure. The Structure Module achieves this through Invariant Point Attention (IPA), a mechanism that works in local coordinate frames attached to each residue.

3. Input Embedding: Translating Biology into Tensors

Every deep learning system must bridge the gap between its domain and the world of tensors. For AlphaFold2, this means encoding amino acid sequences, evolutionary alignments, and (optionally) structural templates into numerical representations.

3.1 What Goes In

AlphaFold2 accepts three categories of input:

Target sequence. The protein whose structure we want to predict, represented as a string of amino acid identifiers. A sequence like MVLSPADKTN... is converted to numerical indices (methionine \(\to\) 0, valine \(\to\) 1, and so on) and then to one-hot vectors of length 21 (20 standard amino acids plus a gap token).

Multiple sequence alignment. Thousands of related sequences, each aligned to the target. Each position in each sequence is encoded with features indicating amino acid identity, insertion counts, and deletion states—49 features per position in total.

Template structures (optional). Experimentally determined structures of related proteins. If the database contains a homolog with, say, 40% sequence identity, its backbone coordinates provide geometric clues.

3.2 Creating the Initial Representations

The embedding layer transforms raw inputs into the MSA and pair representations that the Evoformer will refine. The pair representation starts simple: an additive combination of left-residue features, right-residue features, and relative-position encodings.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

class InputEmbedding(nn.Module):

"""Embed input features into MSA and pair representations.

Dimensions:

c_m: MSA representation feature size (default 256)

c_z: pair representation feature size (default 128)

"""

def __init__(self, c_m: int = 256, c_z: int = 128):

super().__init__()

self.c_m = c_m

self.c_z = c_z

# Project 49-dim MSA features to c_m

self.msa_embedding = nn.Linear(49, c_m)

# Separate projections for left / right residues in the pair

self.left_single = nn.Linear(21, c_z)

self.right_single = nn.Linear(21, c_z)

# Relative position: clipped to [-32, +32], giving 65 bins

self.relpos_embedding = nn.Embedding(65, c_z)

def forward(self, msa_feat, target_feat, residue_index):

"""

Args:

msa_feat: [N_seq, L, 49] per-sequence, per-position features

target_feat: [L, 21] one-hot target sequence

residue_index: [L] integer residue positions

Returns:

msa_repr: [N_seq, L, c_m]

pair_repr: [L, L, c_z]

"""

# --- MSA representation ---

msa_repr = self.msa_embedding(msa_feat) # [N_seq, L, c_m]

# --- Pair representation ---

left = self.left_single(target_feat) # [L, c_z]

right = self.right_single(target_feat) # [L, c_z]

pair_repr = left[:, None, :] + right[None, :, :] # broadcast to [L, L, c_z]

# Add relative position encoding

d = residue_index[:, None] - residue_index[None, :] # [L, L]

d = torch.clamp(d + 32, 0, 64) # shift so range is [0, 64]

pair_repr = pair_repr + self.relpos_embedding(d)

return msa_repr, pair_repr

The relative position encoding gives the network a prior: residues that are close in sequence (like positions 15 and 16) receive different encodings than residues far apart (like positions 15 and 150). This prior is biologically sensible because sequence-local residues are more likely to be spatially close.

3.3 Key Dimensions

Several dimension constants appear throughout AlphaFold2. Keeping track of them helps when reading code or the original paper.

| Representation | Shape | Typical size | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSA | \([N_{\text{seq}} \times L \times c_m]\) | \(c_m = 256\) | Per-sequence, per-residue features |

| Pair | \([L \times L \times c_z]\) | \(c_z = 128\) | Pairwise residue relationships |

| Single | \([L \times c_s]\) | \(c_s = 384\) | Per-residue features for Structure Module |

4. The Evoformer: Where Evolution Meets Attention

The Evoformer is the heart of AlphaFold2. It is a stack of 48 nearly identical blocks, each of which refines both the MSA representation and the pair representation.

flowchart TB

subgraph EvoBlock["Single Evoformer Block"]

MSA_IN["MSA repr\n(N×L×c_m)"] --> ROW["Row Attention\n(+ pair bias)"]

ROW --> COL["Column Attention"]

COL --> MSA_FF["MSA Transition\n(FFN)"]

MSA_FF --> MSA_OUT["Updated MSA"]

PAIR_IN["Pair repr\n(L×L×c_z)"] --> TRI_OUT["Triangular\nMultiplicative\nUpdate (outgoing)"]

TRI_OUT --> TRI_IN["Triangular\nMultiplicative\nUpdate (incoming)"]

TRI_IN --> TRI_ATT_S["Triangular\nSelf-Attention\n(starting node)"]

TRI_ATT_S --> TRI_ATT_E["Triangular\nSelf-Attention\n(ending node)"]

TRI_ATT_E --> PAIR_FF["Pair Transition\n(FFN)"]

PAIR_FF --> PAIR_OUT["Updated Pair"]

MSA_FF -->|"Outer product\nmean"| TRI_OUT

PAIR_IN -->|"Bias"| ROW

end

style ROW fill:#fff3e0,stroke:#FF9800

style TRI_OUT fill:#e8f4fd,stroke:#2196F3

style TRI_IN fill:#e8f4fd,stroke:#2196F3

The name telegraphs its purpose: a transformer designed to process evolutionary information.

What makes the Evoformer distinctive is not raw size but architectural specificity. Every sub-component targets a particular biological signal. We examine each in turn.

4.1 MSA Row Attention with Pair Bias

What it does. Within a single sequence of the MSA, each position attends to every other position. This is analogous to self-attention in a standard transformer, but with an important addition: the attention logits are biased by the pair representation.

Why it matters. When position \(i\) decides how much attention to pay to position \(j\), it considers not only the MSA features at those positions but also what the pair representation says about the \((i, j)\) relationship. If the pair representation encodes that positions \(i\) and \(j\) are likely in structural contact, the attention mechanism gives them more opportunity to exchange information.

This creates a feedback loop. The pair representation influences how the MSA is processed, and later, information from the MSA will update the pair representation.

Formally, given query \(Q\), key \(K\), and value \(V\) matrices derived from the MSA representation, and a bias term \(b_{ij}\) derived from the pair representation:

\[\text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}\!\left(\frac{QK^\top}{\sqrt{d_k}} + b_{ij}\right) V\]where \(d_k\) is the dimension of each attention head.

class MSARowAttentionWithPairBias(nn.Module):

"""MSA row-wise self-attention, biased by the pair representation.

For each sequence s in the MSA, positions attend to each other

along the residue axis. The pair representation injects relational

information into the attention logits.

"""

def __init__(self, c_m: int = 256, c_z: int = 128, n_heads: int = 8):

super().__init__()

self.c_m = c_m

self.n_heads = n_heads

self.head_dim = c_m // n_heads

self.layer_norm_m = nn.LayerNorm(c_m)

self.layer_norm_z = nn.LayerNorm(c_z)

# Standard Q / K / V projections

self.to_q = nn.Linear(c_m, c_m, bias=False)

self.to_k = nn.Linear(c_m, c_m, bias=False)

self.to_v = nn.Linear(c_m, c_m, bias=False)

# Project pair features to per-head bias scalars

self.pair_bias = nn.Linear(c_z, n_heads, bias=False)

# Gated output projection

self.to_out = nn.Linear(c_m, c_m)

self.gate = nn.Linear(c_m, c_m)

def forward(self, msa_repr, pair_repr):

"""

Args:

msa_repr: [N_seq, L, c_m]

pair_repr: [L, L, c_z]

Returns:

updated msa_repr: [N_seq, L, c_m]

"""

N_seq, L, _ = msa_repr.shape

m = self.layer_norm_m(msa_repr)

z = self.layer_norm_z(pair_repr)

# Q, K, V -> [N_seq, L, n_heads, head_dim]

q = self.to_q(m).view(N_seq, L, self.n_heads, self.head_dim)

k = self.to_k(m).view(N_seq, L, self.n_heads, self.head_dim)

v = self.to_v(m).view(N_seq, L, self.n_heads, self.head_dim)

# Attention logits: [N_seq, n_heads, L, L]

attn = torch.einsum('bihd,bjhd->bhij', q, k) / (self.head_dim ** 0.5)

# Pair bias: [L, L, n_heads] -> [1, n_heads, L, L]

bias = self.pair_bias(z).permute(2, 0, 1).unsqueeze(0)

attn = attn + bias

attn = torch.softmax(attn, dim=-1)

out = torch.einsum('bhij,bjhd->bihd', attn, v)

out = out.reshape(N_seq, L, self.c_m)

# Gating: the network learns when to incorporate new information

gate = torch.sigmoid(self.gate(m))

out = gate * self.to_out(out)

return msa_repr + out # residual connection

The gating mechanism at the output deserves attention. Rather than always adding the full attention output, the network learns a per-element sigmoid gate that controls how much new information to incorporate. This pattern appears throughout AlphaFold2 and helps stabilize gradient flow during training.

4.2 MSA Column Attention

What it does. While row attention examines relationships within a single sequence, column attention looks at the same position across different sequences in the MSA.

Why it matters. Column attention is where co-evolutionary signals become explicit. When the network attends across sequences at a given column, it discovers patterns such as “whenever this position is hydrophobic, that other position (in the same column of the pair representation) also tends to be hydrophobic.” Each sequence in the MSA represents a different evolutionary experiment—a different organism’s solution to the same folding problem. Column attention aggregates the lessons of those experiments.

This operation is computationally expensive because it attends over potentially thousands of sequences. AlphaFold2 mitigates this cost by sampling down to 512 sequences for the extra MSA stack and by using axial attention: row and column attention are applied sequentially rather than computing full two-dimensional attention over the entire \(N_{\text{seq}} \times L\) grid4.

4.3 Triangular Updates: Enforcing Geometric Consistency

Now we come to one of AlphaFold2’s most elegant ideas.

Consider three residues \(A\), \(B\), and \(C\). If \(A\) is close to \(B\) and \(B\) is close to \(C\), what can we infer about the \(A\)–\(C\) relationship? In principle, \(A\) and \(C\) could be anywhere within the sum of the two distances (the triangle inequality). But proteins are densely packed, and real constraints are far tighter than the worst-case triangle inequality.

The triangular updates pass messages around triangles in the pair representation, enforcing this kind of three-body consistency.

flowchart LR

subgraph Triangle["Triangle Inequality Constraint"]

A((A)) -->|"z_ij"| B((B))

B -->|"z_jk"| C((C))

A -->|"z_ik"| C

end

subgraph Update["Triangular Multiplicative Update"]

direction TB

ZIK["z(i,k)"] --> GATE_A["Gate a_ik"]

ZJK["z(j,k)"] --> GATE_B["Gate b_jk"]

GATE_A --> MULT["a_ik ⊙ b_jk"]

GATE_B --> MULT

MULT -->|"Sum over k"| ZIJ["Update z(i,j)"]

end

Triangle -->|"For each\nthird vertex k"| Update

There are four triangular operations in each Evoformer block—two multiplicative updates and two attention variants—each providing a different view of the geometric constraints.

4.3.1 Triangular Multiplicative Update (Outgoing Edges)

For each pair \((i, j)\), aggregate information from all pairs \((i, k)\) and \((j, k)\) that share a third node \(k\):

\[z_{ij} \leftarrow z_{ij} + \sum_k a_{ik} \odot b_{jk}\]Here \(a_{ik}\) and \(b_{jk}\) are gated linear projections of the pair representation, and \(\odot\) denotes element-wise multiplication. The sum over \(k\) accumulates evidence from every possible third vertex.

4.3.2 Triangular Multiplicative Update (Incoming Edges)

The same idea, but the summation runs over the other index:

\[z_{ij} \leftarrow z_{ij} + \sum_k a_{ki} \odot b_{kj}\]The outgoing variant asks “which residues do \(i\) and \(j\) both point to?” The incoming variant asks “which residues both point to \(i\) and \(j\)?”

class TriangularMultiplicativeUpdate(nn.Module):

"""Triangular multiplicative update for the pair representation.

Enforces three-body geometric consistency by aggregating

information from triangles (i, j, k) in the pair graph.

Args:

c_z: pair representation feature dimension

c_hidden: hidden projection dimension

mode: 'outgoing' or 'incoming'

"""

def __init__(self, c_z: int = 128, c_hidden: int = 128, mode: str = 'outgoing'):

super().__init__()

self.mode = mode

self.layer_norm = nn.LayerNorm(c_z)

# Gated projections for the two edges of each triangle

self.left_proj = nn.Linear(c_z, c_hidden)

self.right_proj = nn.Linear(c_z, c_hidden)

self.left_gate = nn.Linear(c_z, c_hidden)

self.right_gate = nn.Linear(c_z, c_hidden)

# Output with gating

self.output_gate = nn.Linear(c_z, c_z)

self.output_proj = nn.Linear(c_hidden, c_z)

self.final_norm = nn.LayerNorm(c_hidden)

def forward(self, pair_repr):

"""

Args:

pair_repr: [L, L, c_z]

Returns:

updated pair_repr: [L, L, c_z]

"""

z = self.layer_norm(pair_repr)

# Project and gate each edge

left = self.left_proj(z) * torch.sigmoid(self.left_gate(z))

right = self.right_proj(z) * torch.sigmoid(self.right_gate(z))

if self.mode == 'outgoing':

# z_ij += sum_k left[i,k] * right[j,k]

out = torch.einsum('ikc,jkc->ijc', left, right)

else:

# z_ij += sum_k left[k,i] * right[k,j]

out = torch.einsum('kic,kjc->ijc', left, right)

out = self.final_norm(out)

out = self.output_proj(out)

gate = torch.sigmoid(self.output_gate(pair_repr))

return pair_repr + gate * out

4.3.3 Triangular Attention

The triangular attention operations serve a similar purpose but use attention rather than element-wise multiplication to aggregate information. Two variants exist—starting-node and ending-node—providing complementary views of the triangle.

class TriangularAttention(nn.Module):

"""Triangular self-attention over the pair representation.

For 'starting' mode: for each starting node i, pairs (i,j) attend

over other pairs (i,k), biased by (j,k).

For 'ending' mode: transpose, attend, transpose back.

"""

def __init__(self, c_z: int = 128, n_heads: int = 4, mode: str = 'starting'):

super().__init__()

self.c_z = c_z

self.n_heads = n_heads

self.head_dim = c_z // n_heads

self.mode = mode

self.layer_norm = nn.LayerNorm(c_z)

self.to_q = nn.Linear(c_z, c_z, bias=False)

self.to_k = nn.Linear(c_z, c_z, bias=False)

self.to_v = nn.Linear(c_z, c_z, bias=False)

# Bias derived from the pair representation itself

self.bias_proj = nn.Linear(c_z, n_heads, bias=False)

self.to_out = nn.Linear(c_z, c_z)

self.gate = nn.Linear(c_z, c_z)

def forward(self, pair_repr):

"""

Args:

pair_repr: [L, L, c_z]

Returns:

updated pair_repr: [L, L, c_z]

"""

L = pair_repr.shape[0]

if self.mode == 'ending':

pair_repr = pair_repr.transpose(0, 1)

z = self.layer_norm(pair_repr)

q = self.to_q(z).view(L, L, self.n_heads, self.head_dim)

k = self.to_k(z).view(L, L, self.n_heads, self.head_dim)

v = self.to_v(z).view(L, L, self.n_heads, self.head_dim)

# For each row i, positions j attend over positions k

attn = torch.einsum('ijhd,ikhd->hijk', q, k) / (self.head_dim ** 0.5)

# Bias from pair representation

bias = self.bias_proj(z).permute(2, 0, 1).unsqueeze(1)

attn = attn + bias

attn = torch.softmax(attn, dim=-1)

out = torch.einsum('hijk,ikhd->ijhd', attn, v)

out = out.reshape(L, L, self.c_z)

gate = torch.sigmoid(self.gate(pair_repr))

out = gate * self.to_out(out)

result = pair_repr + out

if self.mode == 'ending':

result = result.transpose(0, 1)

return result

Why both multiplicative updates and attention? They capture different aspects of geometric constraints. The multiplicative updates are “hard” operations that directly compute products summed over triangle vertices. The attention operations are “soft,” letting the network learn which triangles matter most for each pair. Together they provide complementary pathways for enforcing geometric consistency.

4.4 Outer Product Mean: Bridging MSA and Pairs

The MSA representation and pair representation need to communicate. The outer product mean is the primary pathway from MSA to pairs.

The intuition is straightforward. If two positions have correlated feature patterns across the MSA, they are probably structurally related. The outer product computes exactly this correlation:

\[z_{ij} \leftarrow z_{ij} + \frac{1}{N_{\text{seq}}} \sum_{s=1}^{N_{\text{seq}}} m_{si} \otimes m_{sj}\]where \(m_{si}\) is the MSA feature vector for sequence \(s\) at position \(i\), and \(\otimes\) denotes the outer product. For each pair \((i, j)\), we compute the outer product of the projected MSA features at positions \(i\) and \(j\), then average over all sequences.

class OuterProductMean(nn.Module):

"""Transfer information from the MSA to the pair representation

via the mean of outer products across sequences.

This is the primary MSA -> pair communication channel.

"""

def __init__(self, c_m: int = 256, c_z: int = 128, c_hidden: int = 32):

super().__init__()

self.layer_norm = nn.LayerNorm(c_m)

self.left_proj = nn.Linear(c_m, c_hidden)

self.right_proj = nn.Linear(c_m, c_hidden)

self.output = nn.Linear(c_hidden * c_hidden, c_z)

def forward(self, msa_repr):

"""

Args:

msa_repr: [N_seq, L, c_m]

Returns:

pair_update: [L, L, c_z]

"""

m = self.layer_norm(msa_repr)

left = self.left_proj(m) # [N_seq, L, c_hidden]

right = self.right_proj(m) # [N_seq, L, c_hidden]

# Outer product, averaged over sequences

outer = torch.einsum('sic,sjd->ijcd', left, right)

outer = outer / msa_repr.shape[0]

# Flatten the outer-product dimensions and project

outer = outer.reshape(outer.shape[0], outer.shape[1], -1)

return self.output(outer)

4.5 The Complete Evoformer Block

Each Evoformer block orchestrates all the components described above. The information flow within a single block is as follows:

+-------------------------------------------------------------+

| Evoformer Block |

+-------------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| MSA Stack: Pair Stack: |

| +--------------------+ +------------------------+ |

| | MSA Row Attention | | Triangular Mult. Update| |

| | (with pair bias) | | (outgoing edges) | |

| +--------------------+ +------------------------+ |

| | | |

| v v |

| +--------------------+ +------------------------+ |

| | MSA Column | | Triangular Mult. Update| |

| | Attention | | (incoming edges) | |

| +--------------------+ +------------------------+ |

| | | |

| v v |

| +--------------------+ +------------------------+ |

| | MSA Transition | | Triangular Attention | |

| | (feed-forward) | | (starting node) | |

| +--------------------+ +------------------------+ |

| | | |

| | v |

| | +------------------------+ |

| | | Triangular Attention | |

| | | (ending node) | |

| | +------------------------+ |

| | | |

| | v |

| | +------------------------+ |

| | | Pair Transition | |

| | | (feed-forward) | |

| | +------------------------+ |

| | | |

| v v |

| +--------------------------------------------+ |

| | Outer Product Mean (MSA -> Pair) | |

| +--------------------------------------------+ |

| |

+-------------------------------------------------------------+

After 48 of these blocks, the MSA representation has been refined through thousands of attention operations, and the pair representation encodes detailed spatial relationships between all residue pairs. The pair representation now functions as a predicted distance map—a blurry but informative picture of which residues are close in three-dimensional space.

But a distance map is not yet a structure. We need to convert pairwise relationships into actual atomic coordinates.

5. The Structure Module: From Features to Coordinates

The Structure Module is where AlphaFold2 produces its final output: three-dimensional atomic coordinates for every residue. This component introduces Invariant Point Attention (IPA), arguably the most important architectural innovation in the system.

5.1 The Challenge of Three-Dimensional Structure

Protein structures exist in three-dimensional Euclidean space, and that space has symmetries. If you rotate a protein by 90 degrees, it is still the same protein. If you translate it 10 angstroms to the left, the structure is unchanged. These symmetries form the group \(SE(3)\)—the special Euclidean group in three dimensions, consisting of all rotations and translations5.

Any valid structure prediction method must respect these symmetries. Earlier approaches sidestepped the issue by predicting distance matrices or contact maps, which are naturally rotation- and translation-invariant. AlphaFold2 wanted to predict actual coordinates, which required building invariance directly into the architecture.

5.2 Frames: A Language for Protein Geometry

AlphaFold2’s solution is to represent each residue as a rigid body frame—a local coordinate system defined by a rotation and a translation. The backbone atoms of each residue (N, C\(_\alpha\), C) define a natural reference frame.

A frame \(T_i = (R_i, \vec{t}_i)\) for residue \(i\) consists of:

- \(R_i \in SO(3)\): a \(3 \times 3\) rotation matrix (orthogonal, determinant 1)

- \(\vec{t}_i \in \mathbb{R}^3\): a translation vector (the position of C\(_\alpha\))

Any point in space can be expressed either in global coordinates or in the local coordinate system of any frame. Converting between these viewpoints is fundamental to how the Structure Module operates.

class Rigid:

"""Rigid body transformation: rotation + translation.

Represents a frame T = (R, t) that maps local coordinates

to global coordinates via x_global = R @ x_local + t.

"""

def __init__(self, rots, trans):

"""

Args:

rots: [*, 3, 3] rotation matrices

trans: [*, 3] translation vectors

"""

self.rots = rots

self.trans = trans

@staticmethod

def identity(shape, device='cpu'):

"""Create identity frames (no rotation, no translation)."""

rots = torch.eye(3, device=device).expand(*shape, 3, 3).clone()

trans = torch.zeros(*shape, 3, device=device)

return Rigid(rots, trans)

def compose(self, other):

"""Compose two rigid transformations: self * other.

If self = (R1, t1) and other = (R2, t2), then

composed = (R1 @ R2, R1 @ t2 + t1).

"""

new_rots = torch.einsum('...ij,...jk->...ik', self.rots, other.rots)

new_trans = (torch.einsum('...ij,...j->...i', self.rots, other.trans)

+ self.trans)

return Rigid(new_rots, new_trans)

def apply(self, points):

"""Apply transformation to points: R @ x + t."""

return torch.einsum('...ij,...j->...i', self.rots, points) + self.trans

def invert(self):

"""Compute the inverse transformation: (R^T, -R^T @ t)."""

inv_rots = self.rots.transpose(-1, -2)

inv_trans = -torch.einsum('...ij,...j->...i', inv_rots, self.trans)

return Rigid(inv_rots, inv_trans)

5.3 Invariant Point Attention (IPA)

flowchart TB

subgraph IPA["Invariant Point Attention"]

S["Per-residue\nfeatures s_i"] --> Q_S["Scalar Q, K"]

S --> Q_P["Point Q, K\n(in local frame T_i)"]

PAIR["Pair repr\nz_ij"] --> BIAS["Pair Bias b_ij"]

Q_S --> ATTN["Attention Score a_ij"]

BIAS --> ATTN

Q_P -->|"T_i⁻¹ ∘ T_j\ntransform to\nlocal frame"| DIST["Point Distance\n−w_c/2 · ||...||²"]

DIST --> ATTN

ATTN --> SOFT["Softmax"]

SOFT --> OUT["Weighted sum\nof values"]

end

style DIST fill:#e8f4fd,stroke:#2196F3

style ATTN fill:#fff3e0,stroke:#FF9800

Invariant Point Attention is the mechanism that lets the network reason about three-dimensional geometry while remaining invariant to global rotations and translations.

Standard attention computes similarity between queries and keys, both of which are learned projections of input features. IPA extends this by introducing point queries and point keys—three-dimensional coordinates expressed in each residue’s local frame.

When residue \(i\) attends to residue \(j\), the attention score combines three components:

- Scalar attention. Standard query-key dot product on feature vectors, identical to a regular transformer head.

- Pair bias. A projection of the pair representation entry \((i, j)\), injecting relational information.

- Point attention. The squared Euclidean distance between query points and key points when both are expressed in a common reference frame.

The key to invariance is component 3. Each residue generates query points \(\vec{q}_{ip}\) and key points \(\vec{k}_{jp}\) in its own local coordinate system (the subscript \(p\) indexes over multiple query/key points per head). To compare them, we transform residue \(j\)’s key points into residue \(i\)’s coordinate frame by applying \(T_i^{-1} \circ T_j\). The squared distance between the transformed key points and the query points contributes to the attention logit:

\[a_{ij} = \underbrace{q_i \cdot k_j}_{\text{scalar}} + \underbrace{b_{ij}}_{\text{pair bias}} - \underbrace{\frac{w_c}{2} \sum_p \lvert T_i^{-1}(T_j(\vec{k}_{jp})) - \vec{q}_{ip} \rvert^2}_{\text{point distance}}\]where \(w_c\) is a learnable per-head weight that controls how strongly spatial proximity influences attention. The negative sign ensures that closer points receive higher attention.

This distance is invariant to global rotations and translations because both sets of points are expressed relative to the same local frame.

class InvariantPointAttention(nn.Module):

"""Invariant Point Attention (IPA).

SE(3)-invariant attention that combines scalar features,

pair features, and 3D point features expressed in local frames.

Args:

c_s: single representation dimension

c_z: pair representation dimension

n_heads: number of attention heads

n_qk_points: number of query/key point vectors per head

n_v_points: number of value point vectors per head

"""

def __init__(self, c_s=384, c_z=128, n_heads=12,

n_qk_points=4, n_v_points=8):

super().__init__()

self.c_s = c_s

self.n_heads = n_heads

self.head_dim = c_s // n_heads

self.n_qk_points = n_qk_points

self.n_v_points = n_v_points

# Scalar Q / K / V

self.to_q = nn.Linear(c_s, c_s, bias=False)

self.to_k = nn.Linear(c_s, c_s, bias=False)

self.to_v = nn.Linear(c_s, c_s, bias=False)

# Point Q / K / V (3D coordinates in local frame)

self.to_q_points = nn.Linear(c_s, n_heads * n_qk_points * 3)

self.to_k_points = nn.Linear(c_s, n_heads * n_qk_points * 3)

self.to_v_points = nn.Linear(c_s, n_heads * n_v_points * 3)

# Pair bias

self.pair_bias = nn.Linear(c_z, n_heads, bias=False)

# Learnable per-head weight for the point-distance term

self.head_weights = nn.Parameter(torch.zeros(n_heads))

# Output projection (scalar + point + pair outputs concatenated)

out_dim = c_s + n_heads * n_v_points * 3 + n_heads * c_z

self.to_out = nn.Linear(out_dim, c_s)

def forward(self, single_repr, pair_repr, rigids):

"""

Args:

single_repr: [L, c_s] per-residue features

pair_repr: [L, L, c_z] pairwise features

rigids: Rigid with [L] frames

Returns:

updated single_repr: [L, c_s]

"""

L = single_repr.shape[0]

# --- Scalar branch ---

q = self.to_q(single_repr).view(L, self.n_heads, self.head_dim)

k = self.to_k(single_repr).view(L, self.n_heads, self.head_dim)

v = self.to_v(single_repr).view(L, self.n_heads, self.head_dim)

# --- Point branch ---

q_pts = self.to_q_points(single_repr).view(

L, self.n_heads, self.n_qk_points, 3)

k_pts = self.to_k_points(single_repr).view(

L, self.n_heads, self.n_qk_points, 3)

v_pts = self.to_v_points(single_repr).view(

L, self.n_heads, self.n_v_points, 3)

# Transform points from local frames to global frame

q_pts_global = rigids.apply(

q_pts.reshape(L, -1, 3)).view(L, self.n_heads, self.n_qk_points, 3)

k_pts_global = rigids.apply(

k_pts.reshape(L, -1, 3)).view(L, self.n_heads, self.n_qk_points, 3)

v_pts_global = rigids.apply(

v_pts.reshape(L, -1, 3)).view(L, self.n_heads, self.n_v_points, 3)

# --- Attention logits ---

# 1. Scalar attention

attn_scalar = torch.einsum('ihd,jhd->hij', q, k) / (self.head_dim ** 0.5)

# 2. Point attention (negative squared distance -> closer = higher)

pt_diff = (q_pts_global[:, None, :, :, :]

- k_pts_global[None, :, :, :, :]) # [L, L, H, P, 3]

pt_dist_sq = (pt_diff ** 2).sum(dim=-1).sum(dim=-1) # [L, L, H]

w_c = torch.softplus(self.head_weights)

attn_pts = -0.5 * w_c * pt_dist_sq.permute(2, 0, 1) # [H, L, L]

# 3. Pair bias

attn_pair = self.pair_bias(pair_repr).permute(2, 0, 1) # [H, L, L]

# Combine and softmax

attn = attn_scalar.permute(2, 0, 1) + attn_pts + attn_pair

attn = torch.softmax(attn, dim=-1) # [H, L, L]

# --- Attended values ---

# Scalar output

out_scalar = torch.einsum('hij,jhd->ihd', attn, v).reshape(L, self.c_s)

# Point output (global frame -> local frame)

out_pts_global = torch.einsum('hij,jhpc->ihpc', attn, v_pts_global)

out_pts_local = rigids.invert().apply(

out_pts_global.reshape(L, -1, 3))

out_pts = out_pts_local.reshape(L, -1)

# Pair output

out_pair = torch.einsum('hij,ijc->ihc', attn, pair_repr).reshape(L, -1)

# Concatenate all outputs and project

out = torch.cat([out_scalar, out_pts, out_pair], dim=-1)

return self.to_out(out)

5.4 Iterative Refinement

The Structure Module does not predict coordinates in a single pass. Instead, it initializes all residue frames to the identity transformation—placing every residue at the origin with default orientation—and iteratively refines them through 8 layers of IPA.

Each iteration:

- Applies IPA to update per-residue features, using the current frames.

- Passes features through a transition (feed-forward) network.

- Predicts a small update to each residue’s frame (a rotation and translation).

- Composes this update with the current frame.

This iterative approach resembles message passing in a graph neural network. Early iterations establish coarse global topology (“this helix packs against that sheet”). Later iterations fine-tune local geometry (“this side chain points inward, not outward”).

class StructureModule(nn.Module):

"""Structure Module: iteratively refines residue frames

from identity to the predicted 3D structure.

Takes the refined MSA and pair representations from the

Evoformer and produces C-alpha coordinates.

Args:

c_s: single representation dimension

c_z: pair representation dimension

n_layers: number of IPA refinement iterations

"""

def __init__(self, c_s: int = 384, c_z: int = 128, n_layers: int = 8):

super().__init__()

self.input_proj = nn.Linear(256, c_s) # project c_m -> c_s

self.ipa_layers = nn.ModuleList([

InvariantPointAttention(c_s, c_z) for _ in range(n_layers)

])

self.transitions = nn.ModuleList([

nn.Sequential(

nn.LayerNorm(c_s),

nn.Linear(c_s, c_s * 4),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(c_s * 4, c_s),

) for _ in range(n_layers)

])

# Predict 6-DOF frame update: 3 rotation angles + 3 translation

self.backbone_update = nn.Linear(c_s, 6)

def forward(self, msa_repr, pair_repr):

"""

Args:

msa_repr: [N_seq, L, c_m]

pair_repr: [L, L, c_z]

Returns:

coords: [L, 3] predicted C-alpha coordinates

frames: Rigid per-residue frames

"""

L = pair_repr.shape[0]

# Initialize single representation from first row of the MSA

# (the first row is the target sequence)

single = self.input_proj(msa_repr[0]) # [L, c_s]

# All frames start at identity

frames = Rigid.identity((L,), device=single.device)

for ipa, transition in zip(self.ipa_layers, self.transitions):

# 1. IPA: update single representation using current frames

single = single + ipa(single, pair_repr, frames)

# 2. Transition: per-residue feed-forward

single = single + transition(single)

# 3. Predict frame update (small rotation + translation)

update = self.backbone_update(single)

rot_angles = update[:, :3] * 0.1 # scale down for stability

trans_update = update[:, 3:]

# Simplified: identity rotation + translation

# (full implementation uses quaternion parameterization)

rot_mat = torch.eye(3, device=single.device).unsqueeze(0).expand(

L, -1, -1).clone()

frame_update = Rigid(rot_mat, trans_update)

# 4. Compose update with current frames

frames = frames.compose(frame_update)

# C-alpha coordinates are the origins of the final frames

coords = frames.trans

return coords, frames

A note on the rotation parameterization: the code above uses a simplified identity rotation for clarity. The actual AlphaFold2 implementation parameterizes rotations using quaternions, which avoid gimbal lock and compose correctly under small updates6.

6. FAPE Loss: Teaching Geometry Through Local Frames

With the architecture in place, we turn to the question of how AlphaFold2 learns. This requires a loss function that captures what it means for a predicted structure to be correct.

6.1 The Problem with RMSD

The standard metric for comparing protein structures is root-mean-square deviation (RMSD): optimally superimpose the predicted and true structures, then compute the average squared displacement of corresponding atoms. RMSD has been the workhorse of structural biology for decades, but it has several problems as a training loss:

- Optimal superposition is not cleanly differentiable. Finding the rotation that minimizes the error involves an eigenvalue decomposition (the Kabsch algorithm), which complicates gradient computation.

- RMSD treats all errors equally. A 2-angstrom error in a floppy loop is penalized the same as a 2-angstrom error in a rigid beta sheet, even though the loop error might be physically reasonable.

- Global sensitivity. A single badly predicted domain can dominate the RMSD, masking accurate predictions elsewhere.

6.2 Frame Aligned Point Error (FAPE)

AlphaFold2’s answer is Frame Aligned Point Error (FAPE). Instead of measuring error in global coordinates, FAPE measures error in local coordinate frames.

For each residue \(i\) with its local frame \(T_i\), we express the positions of all other residues \(j\) in that frame. We do this for both the predicted structure and the true structure. The FAPE loss is the average discrepancy:

\[\text{FAPE} = \frac{1}{L^2} \sum_{i=1}^{L} \sum_{j=1}^{L} \left\lvert T_i^{\text{true},-1}(\vec{x}_j^{\text{true}}) - T_i^{\text{pred},-1}(\vec{x}_j^{\text{pred}}) \right\rvert\]Why is this a good loss function?

- SE(3) invariance. Global rotations and translations cancel out because everything is measured relative to local frames.

- Local accuracy emphasis. If a flexible loop is locally correct but globally displaced, errors in one part of the loop do not propagate to inflate the loss at distant residues.

- Dense gradient signal. Every pair \((i, j)\) contributes independently, providing \(L^2\) terms of supervision rather than a single global scalar.

def fape_loss(pred_frames, pred_coords, true_frames, true_coords,

clamp_distance=10.0):

"""Frame Aligned Point Error (FAPE) loss.

Measures structural accuracy in local coordinate frames,

providing SE(3)-invariant supervision.

Args:

pred_frames: Rigid with [L] predicted frames

pred_coords: [L, 3] predicted C-alpha positions

true_frames: Rigid with [L] ground-truth frames

true_coords: [L, 3] ground-truth C-alpha positions

clamp_distance: maximum per-pair error (angstroms)

Returns:

loss: scalar FAPE loss

"""

L = pred_coords.shape[0]

# Express all coordinates in each frame's local system

# pred_local[i, j] = T_i^{-1}(x_j) for predicted structure

pred_inv = pred_frames.invert()

pred_local = pred_inv.apply(

pred_coords.unsqueeze(0).expand(L, -1, -1).reshape(-1, 3)

).view(L, L, 3)

# Same for ground truth

true_inv = true_frames.invert()

true_local = true_inv.apply(

true_coords.unsqueeze(0).expand(L, -1, -1).reshape(-1, 3)

).view(L, L, 3)

# Per-pair error (Euclidean distance in local frame)

error = torch.sqrt(((pred_local - true_local) ** 2).sum(dim=-1) + 1e-8)

# Clamp to prevent outliers from dominating the gradient

error = torch.clamp(error, max=clamp_distance)

return error.mean()

The clamping at 10 angstroms deserves explanation. If part of the structure is completely wrong, the loss stops increasing beyond the clamp value. This prevents catastrophic gradients from a single misplaced domain and lets the network focus on improving regions where progress is possible.

6.3 Auxiliary Losses: Multi-Task Learning

AlphaFold2 does not rely on FAPE alone. Several auxiliary losses provide additional training signal:

Distogram loss. For each pair of residues, the network predicts a probability distribution over discretized distance bins (e.g., 64 bins from 2 to 22 angstroms). This is a classification loss (cross-entropy) that provides dense pairwise supervision throughout training.

pLDDT loss. A confidence head predicts the per-residue predicted Local Distance Difference Test (pLDDT), a score between 0 and 100 indicating how confident the network is about each residue’s placement. The network is trained to match this prediction to the actual local accuracy, using mean squared error. This teaches the network to “know what it does not know.”

Masked MSA loss. Random positions in the MSA are masked, and the network must reconstruct the masked amino acid identities. This is analogous to BERT’s masked language modeling objective and encourages the network to learn meaningful evolutionary representations7.

def alphafold_loss(predictions, targets, config):

"""Combined AlphaFold2 loss: FAPE + auxiliary terms.

Args:

predictions: dict with keys 'frames', 'coords',

'distogram', 'plddt'

targets: dict with ground-truth values

config: dict mapping loss names to weights

Returns:

total_loss: weighted sum of all terms

losses: dict of individual loss values

"""

losses = {}

# Primary structural loss

losses['fape'] = fape_loss(

predictions['frames'], predictions['coords'],

targets['frames'], targets['coords'],

)

# Distogram: cross-entropy over distance bins

if 'distogram' in predictions:

pred = predictions['distogram'] # [L, L, n_bins]

true = targets['distogram'] # [L, L] integer bin indices

losses['distogram'] = nn.functional.cross_entropy(

pred.reshape(-1, pred.shape[-1]),

true.reshape(-1),

)

# pLDDT: confidence calibration

if 'plddt' in predictions:

losses['plddt'] = nn.functional.mse_loss(

predictions['plddt'],

targets['plddt_true'],

)

total_loss = sum(config.get(k, 1.0) * v for k, v in losses.items())

return total_loss, losses

7. Putting It All Together

Let us step back and see how the pieces assemble into the complete AlphaFold2 pipeline.

+------------------------------------------------------------------+

| AlphaFold2 Pipeline |

+------------------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| +-----------+ +-----------+ +-------------+ +--------+ |

| | Database |--->| Input |--->| Evoformer |--->|Structure| |

| | Search | | Embedding | | (48 blocks) | | Module | |

| +-----------+ +-----------+ +-------------+ +--------+ |

| | | |

| | MSA: [N_seq x L x c_m] | |

| | Pair: [L x L x c_z] v |

| | +----------+ |

| +-------------------------------------------->| 3D Coords| |

| | + pLDDT | |

| +----------+ |

+------------------------------------------------------------------+

Step 1: Database search. Search sequence databases (UniRef, BFD, MGnify) for evolutionary relatives using tools like JackHMMER (a sequence search tool that iteratively builds a profile from the query to find distant homologs) and HHBlits (a faster method that searches databases of precomputed sequence profiles). Build the MSA. Optionally identify template structures from the PDB.

Step 2: Input embedding. Convert MSA features and one-hot sequence encodings into the initial MSA representation \([N_{\text{seq}} \times L \times c_m]\) and pair representation \([L \times L \times c_z]\). Add relative position encodings.

Step 3: Evoformer. Run 48 Evoformer blocks. Each block updates the MSA features through row attention (with pair bias) and column attention, updates pair features through triangular multiplicative updates and triangular attention, and bridges the two representations through the outer product mean.

Step 4: Structure Module. Take the refined MSA and pair representations. Initialize all residue frames to identity. Run 8 iterations of IPA, each time updating per-residue features and composing small frame updates. The frames converge from “everything at the origin” to the predicted three-dimensional structure.

Step 5: Output. Return predicted C\(_\alpha\) coordinates, all-atom positions (via a side-chain prediction head), pLDDT confidence scores per residue, and PAE (predicted aligned error) per residue pair.

Recycling

One additional mechanism warrants mention: recycling. AlphaFold2 runs the entire Evoformer + Structure Module pipeline three times. After each pass, the predicted structure and pair representation are fed back as additional inputs to the next pass. This allows the network to correct mistakes using feedback from its own predictions8.

8. Design Principles and Lessons

AlphaFold2’s success was not accidental. Every component reflects principled thinking about what information matters for protein structure and how neural networks can extract it.

Principle 1: Use Evolutionary Information

Proteins are not designed from scratch; they evolve from ancestors. Related sequences are experiments run by natural selection, each revealing something about the constraints on structure. AlphaFold2 makes MSA processing central, with specialized attention mechanisms that extract co-evolutionary signals.

Principle 2: Model Pairwise Relationships Explicitly

Protein structure is fundamentally about which residues are near which other residues. The pair representation makes these relationships a first-class data structure, and triangular operations enforce that pairwise predictions are geometrically self-consistent.

Principle 3: Respect Symmetry

Three-dimensional space has rotational and translational symmetry. Rather than hoping the network discovers this from data, AlphaFold2 builds invariance into the architecture through local frames and IPA. This is an instance of a broader principle: inductive biases that match the problem domain reduce the burden on learning.

Principle 4: Iterate and Refine

The Evoformer runs 48 blocks. The Structure Module runs 8 iterations. The full pipeline is recycled 3 times. Each pass improves on the last, allowing local decisions to propagate globally and global context to inform local geometry.

Principle 5: Learn What You Do Not Know

The pLDDT confidence head is not an afterthought. AlphaFold2 explicitly models its own uncertainty, distinguishing confident predictions from guesses. This has proven valuable for downstream users: a prediction with pLDDT > 90 can be trusted for atomic-level analysis, while regions below 50 are likely disordered or poorly predicted.

| Principle | Implementation |

|---|---|

| Use evolutionary information | MSA processing in Evoformer |

| Model pairwise relationships | Pair representation + triangular updates |

| Respect symmetry (SE(3)) | IPA, frame-based representation |

| Iterate and refine | 8 IPA iterations, 3 recycling passes |

| Multi-task learning | FAPE + distogram + pLDDT + masked MSA |

| Calibrated confidence | pLDDT head trained against actual local accuracy |

9. Computational Considerations

AlphaFold2 is computationally demanding. Understanding the bottlenecks helps when implementing, adapting, or deploying the architecture.

Memory

Memory scales quadratically with sequence length because of the pair representation. A protein of length \(L = 1000\) requires storing an \([L \times L \times c_z]\) tensor with \(c_z = 128\), consuming roughly \(1000^2 \times 128 \times 4 \approx 512\) MB in float32—and that is just one copy. Attention computations, gradient storage, and intermediate activations multiply this cost several times over.

Bottleneck Operations

- MSA column attention attends over potentially thousands of sequences. AlphaFold2 mitigates this by sampling down to 512 sequences for the “extra MSA” stack and using smaller feature dimensions.

- Triangular attention has complexity \(O(L^3)\) in sequence length because it computes attention over rows (or columns) of the \([L \times L]\) pair representation with biases from the full matrix.

- IPA requires computing pairwise point distances for all \(L^2\) residue pairs, though with \(L\) typically below 1000, this is manageable.

Practical Mitigations

| Technique | What it does |

|---|---|

| Chunked processing | Split long sequences into overlapping windows |

| Mixed precision (BF16) | Halve memory for most operations with minimal accuracy loss |

| Gradient checkpointing | Trade compute for memory by recomputing activations during backward pass |

| MSA subsampling | Limit the number of sequences processed in column attention |

| FlashAttention | An optimized GPU implementation of attention that reduces memory footprint |

For reference, predicting the structure of a single ~400-residue protein takes approximately 5–10 minutes on a single GPU (V100 or A100) when using the full AlphaFold2 pipeline including MSA construction9.

10. Exercises

These problems range from implementation exercises to conceptual questions. They are designed to deepen understanding of the material covered in this lecture.

Exercise 1: Implement MSA Column Attention

Adapt the MSA row attention code to operate over sequences (columns) rather than positions (rows). Specifically:

- The attention dimension changes from \(L\) (positions) to \(N_{\text{seq}}\) (sequences).

- Each position \(j\) independently attends across all sequences.

- The pair bias is no longer applicable (column attention does not use pair bias in AlphaFold2).

Hint: What changes in the einsum indices? Write out the shapes at each step.

Exercise 2: Quaternion-Based Rotation Updates

The Structure Module code above uses a simplified identity rotation for frame updates. Implement a proper quaternion-based rotation:

- Write a function that converts a 4-vector \((q_w, q_x, q_y, q_z)\) to a \(3 \times 3\) rotation matrix.

- Modify

backbone_updateto output 7 values (4 quaternion components + 3 translation) instead of 6. - Ensure that the quaternion is normalized before conversion to a rotation matrix.

Exercise 3: Template Embedding

AlphaFold2 can incorporate structural templates from homologous proteins. Design an embedding scheme that:

- Takes template backbone coordinates \([L, 3, 3]\) (N, C\(_\alpha\), C per residue) and a confidence mask \([L]\).

- Computes pairwise distances and orientations.

- Produces a template contribution to the pair representation \([L, L, c_z]\).

Consider: What features are invariant to global rotation? How should you handle low-confidence or missing template regions?

Exercise 4: Confidence Prediction Head

Implement a pLDDT prediction head:

- Take the single representation \([L, c_s]\) from the Structure Module.

- Predict per-residue confidence scores in \([0, 100]\).

- Compute the training target: the actual lDDT of predicted vs. true coordinates at distance cutoffs of 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 angstroms.

Bonus: How does the pLDDT correlate with B-factors in crystal structures?

Exercise 5: Complexity Analysis

For a protein of length \(L\) with an MSA of \(N\) sequences:

- What is the time complexity of MSA row attention? MSA column attention?

- What is the time and space complexity of the triangular multiplicative update?

- If you double \(L\), how does the total Evoformer runtime change?

References

-

Jumper, J., Evans, R., Pritzel, A., et al. (2021). “Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold.” Nature, 596, 583–589.

-

Anfinsen, C. B. (1973). “Principles that govern the folding of protein chains.” Science, 181(4096), 223–230.

-

Levinthal, C. (1968). “Are there pathways for protein folding?” Journal de Chimie Physique, 65, 44–45.

-

Baek, M., DiMaio, F., Anishchenko, I., et al. (2021). “Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network.” Science, 373(6557), 871–876.

-

Lin, Z., Akin, H., Rao, R., et al. (2023). “Evolutionary-scale prediction of atomic-level protein structure with a language model.” Science, 379(6637), 1123–1130.

-

Ahdritz, G., Bouatta, N., Kadyan, S., et al. (2022). “OpenFold: Retraining AlphaFold2 yields new insights into its learning mechanisms and capacity for generalization.” bioRxiv.

-

Mirdita, M., Schutze, K., Moriwaki, Y., et al. (2022). “ColabFold: Making protein folding accessible to all.” Nature Methods, 19, 679–682.

-

Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2019). “BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding.” Proceedings of NAACL-HLT, 4171–4186.

-

Anfinsen’s thermodynamic hypothesis is sometimes called the “thermodynamic control” model of folding, as opposed to kinetic control, where folding intermediates might trap the protein in a non-native state. ↩

-

The “folding funnel” picture, introduced by Wolynes, Onuchic, and Thirumalai in the 1990s, describes the free-energy landscape as a rugged funnel in which the native state sits at the bottom. ↩

-

The GDT-TS (Global Distance Test - Total Score) metric measures the fraction of residues whose C\(_\alpha\) atoms fall within various distance cutoffs of the true structure after optimal superposition. A score above 90 is generally considered comparable to experimental accuracy for medium-resolution crystal structures. ↩

-

Axial attention factorizes a two-dimensional attention into two one-dimensional passes (one along rows, one along columns). This reduces complexity from \(O(N^2 L^2)\) to \(O(N^2 L + N L^2)\). ↩

-

\(SE(3) = SO(3) \ltimes \mathbb{R}^3\), where \(SO(3)\) is the group of three-dimensional rotations and \(\mathbb{R}^3\) represents translations. A function \(f\) is invariant under \(SE(3)\) if \(f(Rx + t) = f(x)\) for all rotations \(R\) and translations \(t\). A function is equivariant if it transforms consistently: \(f(Rx + t) = Rf(x) + t\). ↩

-

Quaternions represent rotations as 4-vectors \((q_w, q_x, q_y, q_z)\) with unit norm. They compose by quaternion multiplication, avoid the singularities of Euler angles, and are straightforward to convert to rotation matrices. ↩

-

The masked MSA loss was inspired by BERT (Devlin et al., 2019), which trains language models by masking tokens and predicting them from context. In AlphaFold2, the “language” is the MSA, and the masked positions provide self-supervised training signal. ↩

-

Recycling is reminiscent of iterative refinement in classical optimization. Each recycling iteration starts from a better initial point, allowing the Evoformer to focus on refining details rather than establishing global topology from scratch. ↩

-

ColabFold (Mirdita et al., 2022) accelerates AlphaFold2 by replacing the slow JackHMMER-based MSA search with a faster MMseqs2-based approach, reducing total prediction time significantly. ↩