Spherical Equivariant Layers for 3D Atomic Systems

Note: This post is the result of studying this material with Seongsu Kim. For readers who want to go deeper, I highly recommend Sophia Tang's tutorial, Erik Bekkers' lecture series, and Duval et al.'s Hitchhiker's Guide—all three provide comprehensive treatments with beautiful figures.

Introduction

Neural networks for 3D atomic systems—from early work like Tensor Field Networks to modern architectures like MACE and eSCN—achieve strong accuracy by building in rotational equivariance from the ground up. These architectures ensure that when a molecule is rotated in space, the network’s internal representations rotate accordingly, and predicted vector quantities like forces transform correctly.

High-Level Architecture

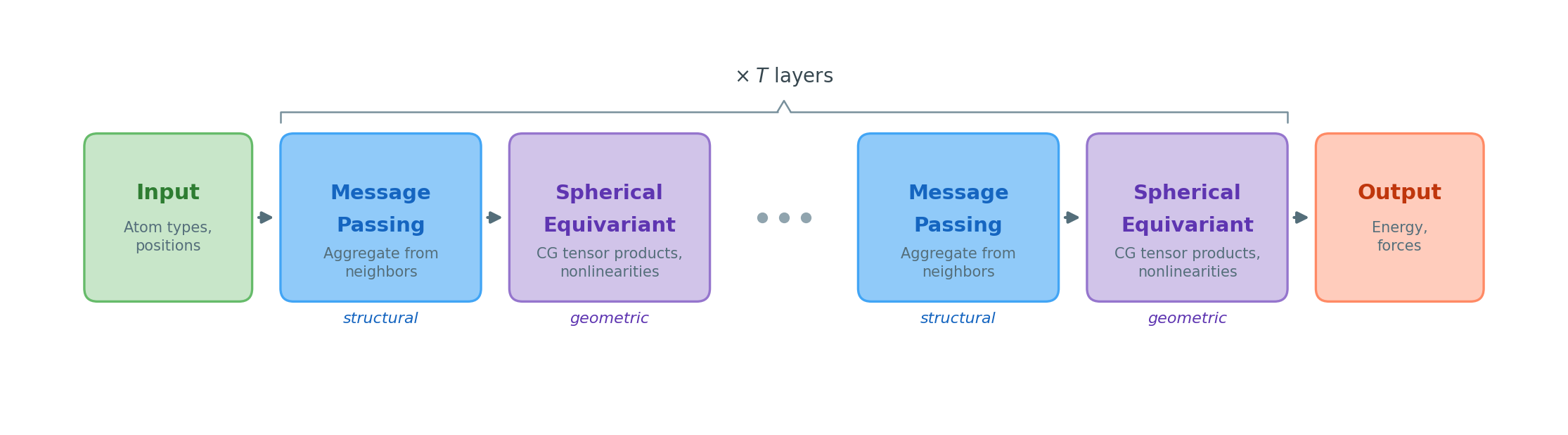

These networks can be understood as having two interleaved components:

-

Message-passing layers: Aggregate information between atoms by collecting features from neighboring atoms and updating each atom’s representation. This handles the structural aspect—how information flows through the molecular graph.

-

Spherical equivariant layers: Transform feature vectors while preserving equivariance. These layers use features built from spherical harmonics that transform under rotation in a well-defined, predictable way—we know exactly how each feature component rotates when the molecule rotates. This handles the geometric aspect—maintaining the relationship between features and 3D space.

The message-passing structure is relatively straightforward (sum over neighbors, apply learned weights). The challenging part—and the focus of this blog post—is the spherical equivariant layers: how do we build layers that transform features expressively while preserving their rotational behavior?

The key insight is that we can’t just use arbitrary neural network operations on geometric features. If we have a feature that represents a direction (like a 3D vector), applying a standard MLP would destroy its geometric meaning—after the MLP, the feature would no longer rotate properly when the molecule rotates. We need specially structured operations that preserve equivariance.

More precisely, a function $f$ is equivariant with respect to a group $G$ if transforming the input by any group element $g$ and then applying $f$ gives the same result as applying $f$ first and then transforming the output:

\[f(g \cdot \mathbf{x}) = g \cdot f(\mathbf{x}) \quad \text{for all } g \in G\]When the input and output live in different spaces, they may transform by different representations—we will make this precise shortly. This is where the mathematical framework of group representations becomes essential. It tells us:

- How to organize features so their transformation under rotation is predictable

- What operations we can apply without breaking equivariance

- How to combine features in ways that respect rotational symmetry

Roadmap

Building spherical equivariant layers requires several mathematical concepts, each serving a specific purpose:

| Section | Why It’s Needed |

|---|---|

| Mathematical Foundations | Define rotations, groups, and representations — the different ways features can transform under symmetries |

| Spherical Harmonics and Spherical Tensors | Provide concrete basis functions for encoding directions, and define feature vectors that transform predictably under rotation |

| Clebsch-Gordan Tensor Products | The core operation for combining spherical tensors to produce new spherical tensors |

| General Architectural Framework | Putting it all together into neural network layers |

By the end of this post, you will understand how spherical harmonics, irreducible representations, and Clebsch-Gordan tensor products come together to build layers that respect the rotational symmetry of 3D space.

Mathematical Foundations

Groups and Symmetries

To build equivariant layers, we first need to precisely define what symmetries we want to preserve. For 3D atomic systems, the key symmetry is rotation: rotating a molecule shouldn’t change its predicted energy, and predicted forces should rotate along with the molecule. The mathematical language of groups gives us the tools to describe these symmetries precisely.

A group is a set equipped with a composition operation that lets us combine symmetry transformations—we can compose them, undo them, and there’s always a “do nothing” transformation. The special orthogonal group $SO(3)$ consists of all 3D rotations, represented as $3 \times 3$ orthogonal matrices with determinant $+1$. This is the primary symmetry group for equivariant neural networks on 3D atomic systems. (Extensions to include reflections or translations are straightforward but beyond our scope here.)

A group action describes how a group transforms the elements of some space $X$. For each group element $g \in G$ and each point $x \in X$, the action produces a transformed point $g \cdot x \in X$, satisfying two properties: the identity element does nothing ($e \cdot x = x$), and composing group elements before acting is the same as acting sequentially ($(g_1 \cdot g_2) \cdot x = g_1 \cdot (g_2 \cdot x)$). For example, $SO(3)$ acts on 3D space by rotating vectors: $R \cdot \mathbf{v} = R\mathbf{v}$. Representations, which we define next, are a special case of group actions where the transformations are linear maps on a vector space.

Group Representations

Now that we know what symmetries to preserve (rotations), we need to understand how different types of features transform under these symmetries. A scalar like energy doesn’t change when you rotate a molecule. A vector like force rotates along with the molecule. Higher-order quantities like quadrupole moments transform in more complex ways. Group representations formalize these different transformation behaviors, allowing us to categorize features by how they respond to rotations.

A representation of a group $G$ is a way of realizing group elements as matrices acting on a vector space $V$. We write $D(g)$ for the matrix corresponding to group element $g$. The key requirement is that the matrices respect the group structure: $D(g_1 \cdot g_2) = D(g_1) D(g_2)$. That is, composing two group elements and then looking up the matrix gives the same result as multiplying the individual matrices.

The vector space $V$ on which these matrices act is called the carrier space.1 A representation has two components:

- The carrier space $V$: the vector space whose elements get transformed

- The representation matrices $D(g)$: the linear transformations that act on $V$

For example, consider 3D vectors like position or velocity. The carrier space is $\mathbb{R}^3$, and for each rotation $R \in SO(3)$, the representation matrix is the $3 \times 3$ rotation matrix itself. When we rotate a vector $\mathbf{v}$, we compute $R\mathbf{v}$—the rotation matrix acts on elements of the carrier space.

Representations are the key to understanding how neural network features should transform under symmetry operations. If we want our feature vectors to transform in a predictable way when the input is rotated, we need to specify which representation governs that transformation. The simplest representation is the trivial representation, where every group element maps to the identity matrix—the carrier space is $\mathbb{R}^1$ (scalars), and rotations leave scalars unchanged. The standard representation of $SO(3)$ uses the $3 \times 3$ rotation matrices on the carrier space $\mathbb{R}^3$—this describes how ordinary 3D vectors transform.

But these are just two examples from an infinite family of representations. A natural question is: can a given representation be broken down into simpler pieces? A representation $D$ is reducible if there exists a change-of-basis matrix $P$ such that:

\[P\,D(g)\,P^{-1} = \begin{bmatrix} D_1(g) & 0 \\ 0 & D_2(g) \end{bmatrix} \quad \text{for all } g \in G\]In the new basis, the representation is a direct sum \(D_1 \oplus D_2\), meaning the carrier space splits into independent subspaces that don’t mix under the group action—each block \(D_i(g)\) is itself a smaller representation. A representation that cannot be decomposed this way is called irreducible.2 Irreducible representations (irreps) are the fundamental building blocks: any representation can be decomposed into a direct sum of irreps by an appropriate change of basis.

For $SO(3)$, the irreps are labeled by non-negative integers $\ell = 0, 1, 2, \ldots$. We write $D^{(\ell)}(R)$ for the representation matrix of the $\ell$-th irrep corresponding to rotation $R$. The $\ell$-th irrep has a carrier space of dimension $2\ell + 1$: the $\ell = 0$ irrep is the trivial representation (1D, scalars), the $\ell = 1$ irrep is the standard representation (3D, vectors), and higher $\ell$ correspond to increasingly complex transformation properties.

Spherical Harmonics and Spherical Tensors

Spherical Harmonics

We now know that features can transform in different ways under rotation (different representations). But how do we actually construct features with these transformation properties? The key idea is simple: given two neighboring atoms, we need a way to encode the direction from one to the other. Spherical harmonics are special functions defined on the unit sphere that do exactly this — they take a direction and return a set of numbers that transform predictably under rotation. Evaluating spherical harmonics at the direction \(\hat{\mathbf{r}}_{ij}\) between atoms \(i\) and \(j\) gives the network its first geometric features, and all subsequent layers build on them.

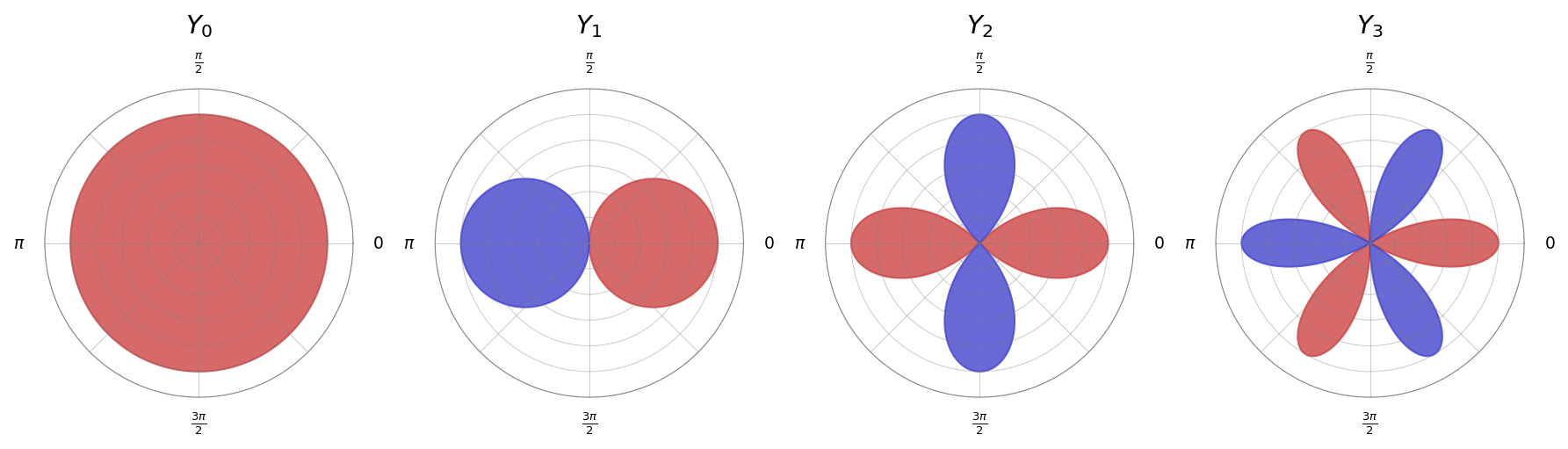

To build intuition, consider the simpler case of the circle first. The circular harmonics $e^{im\phi} = \cos(m\phi) + i\sin(m\phi)$ form a basis for functions on the circle $S^1$. Any function on the circle can be written as a sum of these basis functions (this is the Fourier series). Crucially, each circular harmonic has a simple transformation property under 2D rotations: rotating by angle $\alpha$ multiplies $e^{im\phi}$ by $e^{im\alpha}$. Different values of $m$ transform independently. We write $Y_m(\phi)$ for the real part $\cos(m\phi)$ of each circular harmonic.

Spherical harmonics are the natural extension of this idea from the circle to the sphere. Just as circular harmonics form a basis for functions on $S^1$, spherical harmonics form a basis for functions on the unit sphere $S^2$. And just as circular harmonics have simple transformation properties under 2D rotations, spherical harmonics have simple transformation properties under 3D rotations.

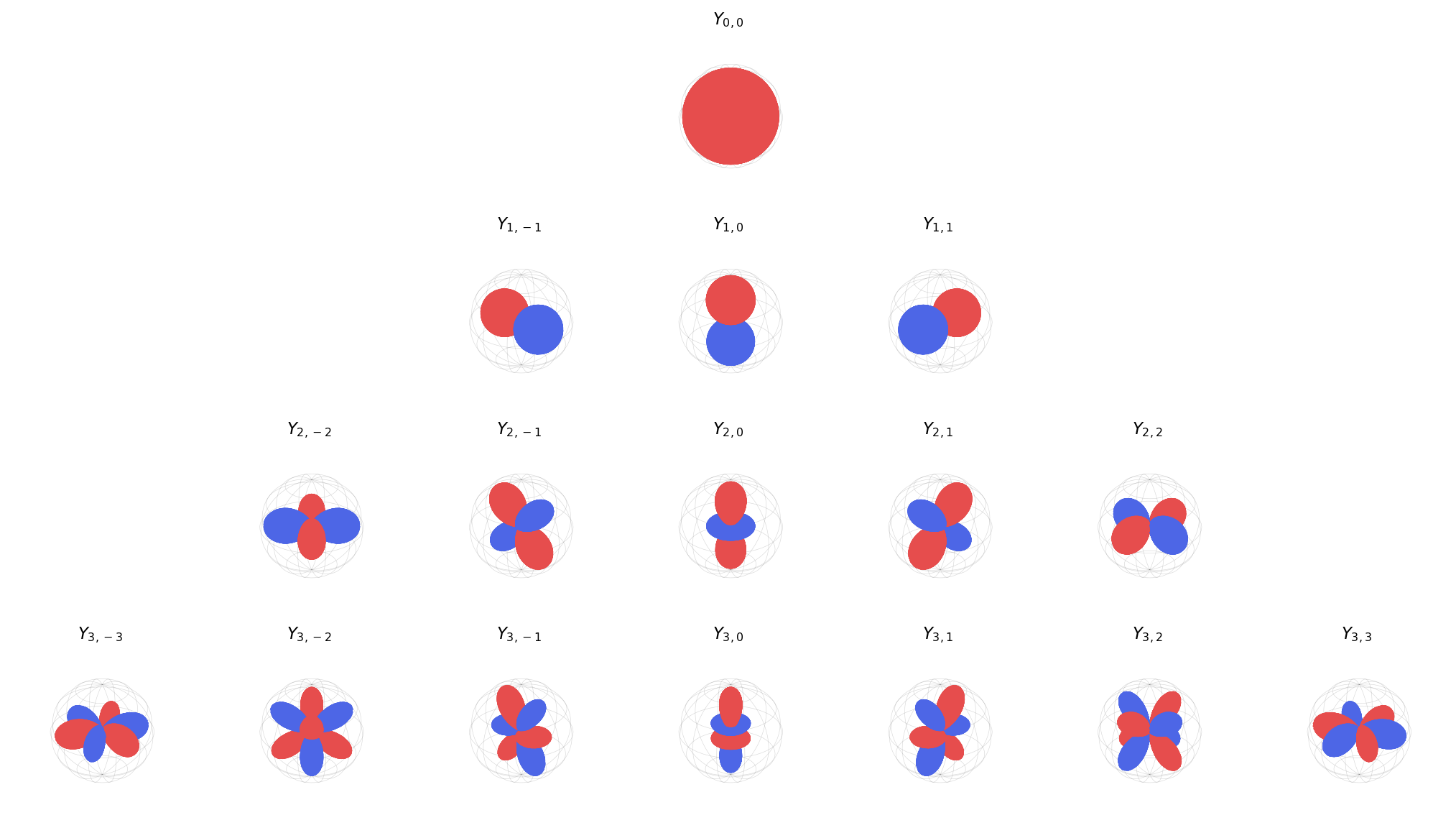

The spherical harmonics $Y_\ell^m$ are special functions on the unit sphere $S^2$ that form a complete orthonormal basis.3 Each $Y_\ell^m: S^2 \to \mathbb{R}$ takes a direction and returns a real number. They are indexed by degree $\ell \geq 0$ and order $-\ell \leq m \leq \ell$, so for each degree $\ell$ there are $2\ell + 1$ spherical harmonics.

Each degree captures a different level of angular complexity:

| $\ell$ | Dim | Intuition |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | A single number that doesn’t change under rotation (e.g., temperature, charge) |

| 1 | 3 | A direction in 3D space—rotates like an arrow (e.g., velocity, electric field) |

| 2 | 5 | An orientation or anisotropy—describes how something stretches along different axes (e.g., polarizability, stress) |

| 3 | 7 | A more complex angular pattern with finer directional structure |

The \(\ell = 1\) row has a concrete interpretation: the three degree-1 spherical harmonics are proportional to the Cartesian coordinates \(x\), \(y\), \(z\) evaluated on the unit sphere. Specifically, \(Y_1^{-1} \propto y\), \(Y_1^0 \propto z\), and \(Y_1^1 \propto x\). A type-1 feature vector \((f_{-1}^{(1)}, f_0^{(1)}, f_1^{(1)})\) is literally a 3D direction — it rotates like an arrow.

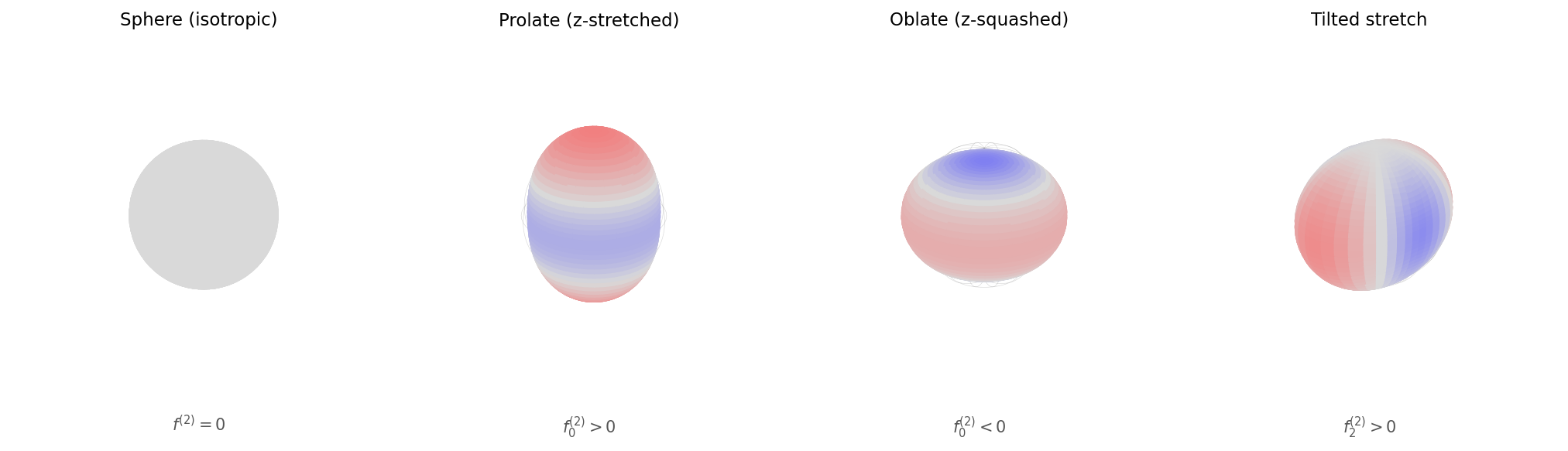

To build intuition for the \(\ell = 2\) row, consider drawing a surface whose radius at each direction \(\hat{\mathbf{r}}\) is determined by a combination of type-0 and type-2 spherical harmonics:

\[r(\hat{\mathbf{r}}) = f^{(0)} Y_0^0(\hat{\mathbf{r}}) + \sum_{m=-2}^{2} f_m^{(2)} Y_2^m(\hat{\mathbf{r}})\]When only the type-0 coefficient is nonzero, \(r\) is constant in every direction — a perfect sphere. Adding type-2 coefficients deforms this sphere into an ellipsoid, capturing how something stretches or compresses along different directions. The sign and choice of component determine whether the shape stretches along the z-axis (prolate), squashes along it (oblate), or tilts the stretch into the xy-plane.

Wigner-D Matrices

The crucial property of spherical harmonics is how they transform under rotations. When we rotate the coordinate system by a rotation $R \in SO(3)$, the spherical harmonics of degree $\ell$ mix among themselves according to a matrix called the Wigner-D matrix:

\[D^{(\ell)}: SO(3) \to \mathbb{R}^{(2\ell+1) \times (2\ell+1)}\]For each degree $\ell$, the Wigner-D matrix takes a rotation $R$ and returns a $(2\ell+1) \times (2\ell+1)$ matrix. We write \(D^{(\ell)}_{mm'}(R)\) for the $(m, m’)$-th entry.4 Concretely, if $\hat{\mathbf{r}}$ denotes a unit direction vector (a point on the sphere), then evaluating a spherical harmonic at the rotated direction $R^{-1}\hat{\mathbf{r}}$ is equivalent to mixing the spherical harmonics evaluated at the original direction:

\[Y_\ell^m(R^{-1}\hat{\mathbf{r}}) = \sum_{m'=-\ell}^{\ell} D^{(\ell)}_{mm'}(R) \, Y_\ell^{m'}(\hat{\mathbf{r}})\]This is the key equation: rotating a spherical harmonic of degree $\ell$ produces a linear combination of same-degree harmonics, and the Wigner-D matrix contains the mixing coefficients. Spherical harmonics of different degrees never mix — they transform independently.

For each degree $\ell$, the $2\ell + 1$ spherical harmonics ${Y_\ell^{-\ell}, Y_\ell^{-\ell+1}, \ldots, Y_\ell^{\ell}}$ span a $(2\ell+1)$-dimensional vector space. This vector space is the carrier space for the $\ell$-th irreducible representation of $SO(3)$, and the Wigner-D matrix $D^{(\ell)}(R)$ is the representation matrix that acts on it. Any linear combination of degree-$\ell$ spherical harmonics can be written as a vector of $2\ell+1$ coefficients, and when we rotate the coordinate system, these coefficients transform by multiplication with the Wigner-D matrix.

The Wigner-D matrices satisfy the representation property: composing two rotations and then finding the representation matrix gives the same result as multiplying the individual representation matrices. At each degree the Wigner-D matrix takes a specific form: $D^{(0)}(R) = 1$ for all rotations (scalars are invariant), $D^{(1)}(R)$ is equivalent to the ordinary $3 \times 3$ rotation matrix, and $D^{(2)}(R)$ is a $5 \times 5$ matrix that transforms the independent components of a traceless symmetric tensor.

In equivariant neural networks, spherical harmonics serve two purposes. First, they provide a way to encode directional information about the relative positions of atoms—given a displacement vector between atoms $i$ and $j$, we can compute the spherical harmonics of the direction to obtain an equivariant encoding. Second, the Wigner-D matrices tell us exactly how to construct feature vectors that transform correctly under rotations.

Spherical Tensors

With spherical harmonics providing our basis, we can now define the feature vectors used in equivariant neural networks. A spherical tensor5 of degree $\ell$ is a $(2\ell+1)$-dimensional vector $\mathbf{f}^{(\ell)} \in \mathbb{R}^{2\ell+1}$ that transforms under rotation $R$ according to the Wigner-D matrix:

\[\mathbf{f}^{(\ell)} \mapsto D^{(\ell)}(R) \, \mathbf{f}^{(\ell)}\]The carrier space is $\mathbb{R}^{2\ell+1}$—the same space spanned by the degree-$\ell$ spherical harmonics. The components of a spherical tensor are indexed by order $m \in {-\ell, \ldots, \ell}$, mirroring the spherical harmonic indices. In other words, spherical tensors live in the carrier spaces of $SO(3)$ irreps that we defined through spherical harmonics. This is why we call the layers that operate on these features spherical equivariant layers. A natural example of a spherical tensor is the vector of all degree-$\ell$ spherical harmonics evaluated at a direction $\hat{\mathbf{r}}$, which we write as \(Y^{(\ell)}(\hat{\mathbf{r}}) = (Y_\ell^{-\ell}(\hat{\mathbf{r}}), \ldots, Y_\ell^{\ell}(\hat{\mathbf{r}}))^T \in \mathbb{R}^{2\ell+1}\).

Modern equivariant networks maintain features as direct sums of spherical tensors of multiple degrees. A direct sum (denoted $\oplus$) simply means concatenating vectors that transform independently—each block has its own transformation rule:

\[\mathbf{f} = \mathbf{f}^{(0)} \oplus \mathbf{f}^{(1)} \oplus \mathbf{f}^{(2)} \oplus \cdots \oplus \mathbf{f}^{(L)}\]where $L$ is the maximum degree used in the network. Each component $\mathbf{f}^{(\ell)}$ may have multiple “channels”—for instance, we might have 64 independent type-1 vectors at each node, giving a type-1 feature of shape $(3, 64)$. The total feature at a node is the concatenation of all these components, and under rotation, each component transforms independently according to its type.

This multi-type structure is essential for expressivity. Using only type-0 (scalar) features would give us an invariant network that cannot predict vector quantities like forces. Using only type-1 (vector) features would limit our ability to represent more complex angular dependencies. By including multiple types up to some maximum degree $L$, we can represent arbitrarily complex angular functions while maintaining exact equivariance.

Clebsch-Gordan Tensor Products

Neural network layers need to combine features—for example, combining a node’s features with edge information. For equivariant layers, we need an operation that combines spherical tensors while preserving their transformation properties. The Clebsch-Gordan tensor product is this operation.

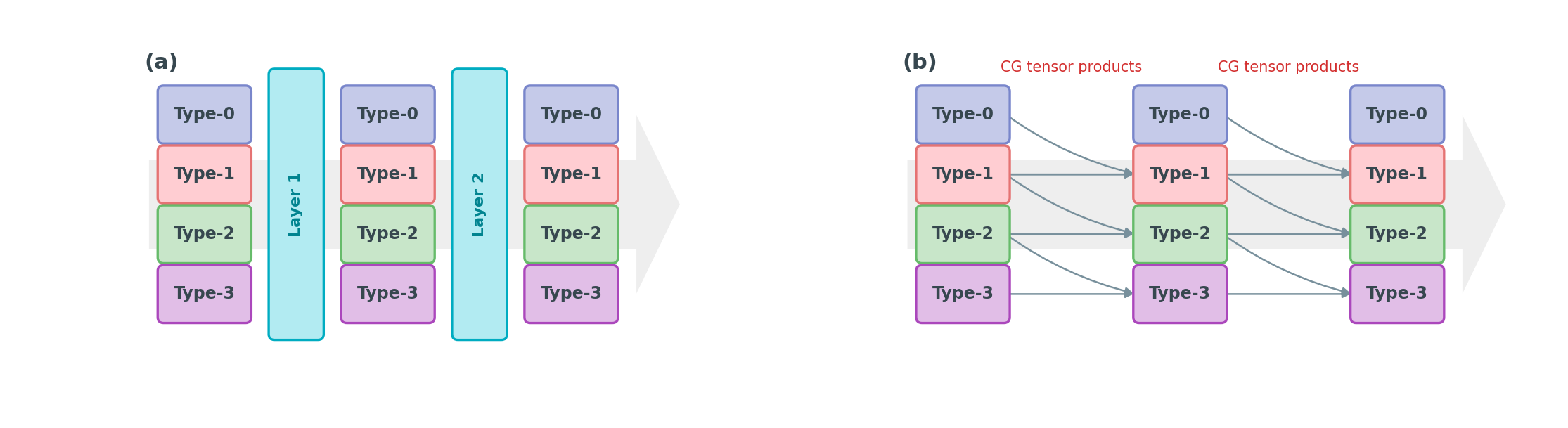

Think of it as building a neural network where features at each layer are organized by type (type-0 scalars, type-1 vectors, type-2, etc.). A standard MLP would destroy the equivariance structure, so instead the “linear layer” is a CG tensor product: it takes the multi-type feature, mixes contributions across types according to the CG coefficients, and produces a new multi-type feature. Panel (a) below shows the compact view; panel (b) reveals the cross-type connections that a single layer performs.

Overview

How do we combine two spherical tensors while preserving equivariance? The naive approach—taking the ordinary tensor product—produces a result that transforms equivariantly, but the resulting space is not organized as a direct sum of irreps. The Clebsch-Gordan (CG) tensor product solves this by applying a change-of-basis transformation that reorganizes the tensor product space into irreducible components.

The key insight is:

- The naive tensor product gives a valid equivariant representation, but it’s reducible

- A change-of-basis transformation can decompose this into a direct sum of irreps

- The CG coefficients define exactly this change of basis

The Naive Tensor Product

Consider two spherical tensors $\mathbf{x}^{(\ell_1)}$ and $\mathbf{y}^{(\ell_2)}$ of types $\ell_1$ and $\ell_2$. Recall that a type-$\ell$ feature has $2\ell + 1$ components, indexed by order $m$ ranging from $-\ell$ to $\ell$. We write $x^{(\ell_1)}_{m_1}$ for the $m_1$-th component of $\mathbf{x}^{(\ell_1)}$.

The tensor product $\otimes$ computes all pairwise products of their components:

\[(\mathbf{x}^{(\ell_1)} \otimes \mathbf{y}^{(\ell_2)})_{m_1, m_2} = x^{(\ell_1)}_{m_1} \cdot y^{(\ell_2)}_{m_2}\]This produces a $(2\ell_1 + 1) \times (2\ell_2 + 1)$-dimensional object. For example, combining two type-1 vectors ($\ell_1 = \ell_2 = 1$, each with 3 components) gives $3 \times 3 = 9$ values.

How does this tensor product transform under rotation? When both inputs are rotated, the outer product matrix transforms by left- and right-multiplication with Wigner-D matrices:

\[\mathbf{x}^{(\ell_1)} \otimes \mathbf{y}^{(\ell_2)} \;\mapsto\; D^{(\ell_1)}(R)\,\bigl(\mathbf{x}^{(\ell_1)} \otimes \mathbf{y}^{(\ell_2)}\bigr)\,D^{(\ell_2)}(R)^T\]To treat this as a single feature vector (which is more natural for neural networks), we vectorize the matrix—stacking its columns into a vector \(\operatorname{vec}(\mathbf{x}^{(\ell_1)} \otimes \mathbf{y}^{(\ell_2)})\) of dimension \((2\ell_1+1)(2\ell_2+1)\). Using the standard identity \(\operatorname{vec}(ABC) = (C^T \otimes A)\,\operatorname{vec}(B)\) for the Kronecker product \(\otimes\), the transformation rule becomes:

\[\begin{aligned} R \cdot \operatorname{vec}(\mathbf{x}^{(\ell_1)} \otimes \mathbf{y}^{(\ell_2)}) &= \underbrace{\bigl(D^{(\ell_2)}(R) \otimes D^{(\ell_1)}(R)\bigr)}_{\text{new group representation}}\;\operatorname{vec}(\mathbf{x}^{(\ell_1)} \otimes \mathbf{y}^{(\ell_2)}) \end{aligned}\]The Kronecker product \(D^{(\ell_2)}(R) \otimes D^{(\ell_1)}(R)\) is a new, larger representation matrix of dimension \((2\ell_1+1)(2\ell_2+1)\). This is still a valid equivariant representation—it respects the group structure—but it is reducible: it can be decomposed into smaller, independent blocks.

The Change-of-Basis Solution

The vectorized tensor product’s components don’t transform independently by type—they are mixed together by the large Kronecker product matrix. We want features organized as a direct sum of irreps, where each block transforms independently by its own Wigner-D matrix.

Representation theory guarantees that any reducible representation can be block-diagonalized by a change of basis. There exists an orthogonal change-of-basis matrix \(\mathbf{C}\) such that:

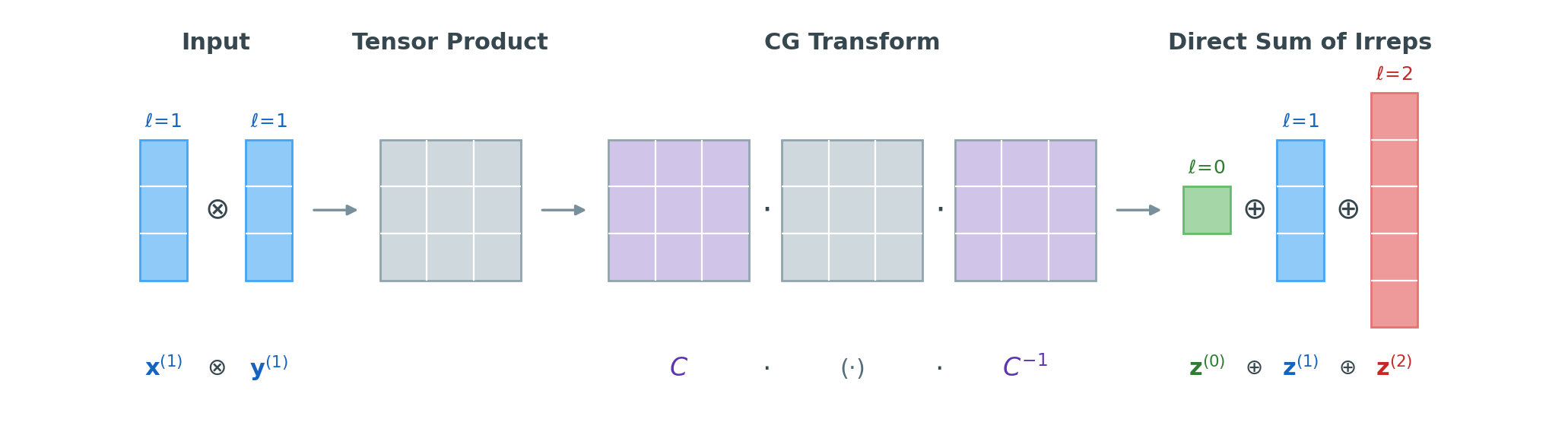

\[\begin{aligned} & R \cdot \operatorname{vec}(\mathbf{x}^{(\ell_1)} \otimes \mathbf{y}^{(\ell_2)}) \\[4pt] &\quad= \mathbf{C}^{-1}\begin{bmatrix} D^{(\ell'_1)}(R) & 0 & 0 & \cdots \\ 0 & D^{(\ell'_2)}(R) & 0 & \cdots \\ 0 & 0 & D^{(\ell'_3)}(R) & \cdots \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots \end{bmatrix} \mathbf{C}\;\operatorname{vec}(\mathbf{x}^{(\ell_1)} \otimes \mathbf{y}^{(\ell_2)}) \end{aligned}\]where the output degrees \(\ell'\) range from \(\lvert\ell_1 - \ell_2\rvert\) to \(\ell_1 + \ell_2\). For our \(\ell_1 = \ell_2 = 1\) example, the 9D tensor product decomposes into \(D^{(0)} \oplus D^{(1)} \oplus D^{(2)}\) (dimensions \(1 + 3 + 5 = 9\)).

This motivates the definition of the Clebsch-Gordan (CG) tensor product \(\otimes_{\text{cg}}\), which applies the change of basis directly:

\[\operatorname{vec}(\mathbf{x}^{(\ell_1)} \otimes_{\text{cg}} \mathbf{y}^{(\ell_2)}) \;=\; \mathbf{C}\;\operatorname{vec}(\mathbf{x}^{(\ell_1)} \otimes \mathbf{y}^{(\ell_2)})\]Because \(\mathbf{C}\) absorbs the change of basis, the CG tensor product transforms by the block-diagonal matrix directly—each output block is a spherical tensor that transforms by a single Wigner-D matrix:

\[\begin{aligned} & R \cdot \operatorname{vec}(\mathbf{x}^{(\ell_1)} \otimes_{\text{cg}} \mathbf{y}^{(\ell_2)}) \\[4pt] &\quad= \begin{bmatrix} D^{(\ell'_1)}(R) & 0 & 0 & \cdots \\ 0 & D^{(\ell'_2)}(R) & 0 & \cdots \\ 0 & 0 & D^{(\ell'_3)}(R) & \cdots \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots \end{bmatrix} \operatorname{vec}(\mathbf{x}^{(\ell_1)} \otimes_{\text{cg}} \mathbf{y}^{(\ell_2)}) \end{aligned}\]This is exactly the format we need: a direct sum of irreps where each block transforms independently. The entries of \(\mathbf{C}\) are the Clebsch-Gordan coefficients \(C_{(\ell_1, m_1),(\ell_2, m_2)}^{(\ell, m)}\). The subscript \((\ell_1, m_1), (\ell_2, m_2)\) specifies the two input components, and the superscript \((\ell, m)\) specifies the output component. In component form, the CG tensor product reads:

\[(\mathbf{x}^{(\ell_1)} \otimes_{\text{cg}} \mathbf{y}^{(\ell_2)})^{(\ell)}_m = \sum_{m_1=-\ell_1}^{\ell_1} \sum_{m_2=-\ell_2}^{\ell_2} C_{(\ell_1, m_1),(\ell_2, m_2)}^{(\ell, m)} \, x^{(\ell_1)}_{m_1} \, y^{(\ell_2)}_{m_2}\]This weighted sum over all input component pairs produces outputs that are properly organized by irrep type. For two vectors ($\ell_1 = \ell_2 = 1$), the CG tensor product yields:

- A type-0 (1D scalar): corresponds to the dot product $\mathbf{x} \cdot \mathbf{y}$

- A type-1 (3D vector): corresponds to the cross product $\mathbf{x} \times \mathbf{y}$

- A type-2 (5D quadrupole): corresponds to the traceless symmetric outer product

The CG tensor product is equivariant by construction: rotating both inputs causes each output component to rotate according to its own Wigner-D matrix. This is what allows us to stack multiple layers while maintaining equivariance throughout.

Computational Considerations

A significant challenge with CG tensor products is their computational cost. A naive implementation has complexity $O(L^6)$ where $L$ is the maximum degree, which becomes prohibitive for large $L$. This has motivated substantial research into more efficient implementations. Modern approaches reduce the complexity to $O(L^3)$ through techniques such as aligning features with edge vectors (reducing $SO(3)$ operations to simpler $SO(2)$ operations, as introduced by eSCN), computing only selected output types rather than all possible outputs, and exploiting sparsity patterns in the CG coefficients.

General Architectural Framework

We now have all the mathematical ingredients: groups define our symmetries, representations tell us how features transform, spherical harmonics provide concrete basis functions, spherical tensors are our feature vectors, and CG tensor products let us combine them equivariantly. This section shows how these pieces fit together into a complete neural network layer.

Building Blocks

All modern equivariant architectures for 3D atomic systems share a common framework built from the mathematical components described above. The input is a set of atoms indexed by $i = 1, \ldots, N$, each with a 3D position $\mathbf{r}_i \in \mathbb{R}^3$ and an atom type (element identity). The output might be a scalar property like energy, vector quantities like forces, or more complex tensorial properties.

The network begins by embedding the atom types into type-0 (scalar) features—this is similar to word embeddings in NLP, but the resulting features are rotation-invariant.

The geometric information enters through the edges of the graph: for each pair of neighboring atoms $i$ and $j$, we compute the relative position vector, its length, and its direction. The direction is encoded using spherical harmonics, providing an equivariant representation of the edge geometry.

The core of the network consists of equivariant message passing layers. In each layer, node features are updated by aggregating information from neighboring nodes. Let \(\mathbf{h}_j^{(\ell)}\) denote the type-\(\ell\) spherical tensor at node \(j\). For each neighboring pair of atoms \(i\) and \(j\), we have the distance \(r_{ij} = \lVert \mathbf{r}_j - \mathbf{r}_i \rVert\) and direction \(\hat{\mathbf{r}}_{ij} = (\mathbf{r}_j - \mathbf{r}_i) / r_{ij}\). The message from node \(j\) to node \(i\) is:

\[\mathbf{m}_{ij}^{(\ell_{\text{out}})} = W(r_{ij}) \left( \mathbf{h}_j^{(\ell_{\text{in}})} \otimes_{\text{cg}} Y^{(\ell_f)}(\hat{\mathbf{r}}_{ij}) \right)^{(\ell_{\text{out}})}\]Here, \(Y^{(\ell_f)}(\hat{\mathbf{r}}_{ij})\) encodes the edge direction as spherical harmonics of degree \(\ell_f\), and \(\otimes_{\text{cg}}\) is the CG tensor product that combines the neighbor features \(\mathbf{h}_j^{(\ell_{\text{in}})}\) with this directional encoding. The superscript \((\ell_{\text{out}})\) selects which output irrep type to extract. \(W(r_{ij})\) is a learnable radial function that takes the scalar distance and returns learned weights—because it depends only on distance (not direction), it is rotation-invariant.

The messages are then summed over all neighbors \(\mathcal{N}(i)\) to update the node features: \(\mathbf{h}_i^{(\ell)} \leftarrow \sum_{j \in \mathcal{N}(i)} \mathbf{m}_{ij}^{(\ell)}\). Summation is a natural choice for aggregation because it commutes with rotation.

Nonlinearities and Output

Applying nonlinear activation functions to spherical tensors requires care. If we apply a pointwise nonlinearity like ReLU directly to the components of a type-$\ell$ feature (for $\ell > 0$), we break equivariance because the nonlinearity doesn’t commute with the Wigner-D rotation matrices. There are several solutions to this problem.

The simplest approach is to apply nonlinearities only to type-0 (scalar) features, which are invariant and can be processed with any standard activation function. For higher-type features, we use only linear transformations within each layer, relying on the CG tensor products between layers to provide the necessary nonlinear mixing.

A more sophisticated approach is gated nonlinearity, where we use a scalar quantity (such as the norm of a higher-type feature) to gate the feature: $\mathbf{h}^{(\ell)} \leftarrow \sigma(\lVert\mathbf{h}^{(\ell)}\rVert) \cdot \mathbf{h}^{(\ell)}$, where $\sigma$ is a standard activation function (e.g., sigmoid or SiLU). This preserves equivariance because the norm $\lVert\mathbf{h}^{(\ell)}\rVert$ is rotation-invariant, and multiplying by a scalar preserves the transformation properties.

For the output layer, the approach depends on what quantity we want to predict. For invariant quantities like total energy, we use only the type-0 features and sum over all atoms to get a single scalar. For equivariant quantities like forces on each atom, we can either use the type-1 features directly or compute forces as the negative gradient of the predicted energy: $\mathbf{F} = -\nabla E$. The gradient approach guarantees energy conservation (the forces are conservative), which is important for molecular dynamics simulations, but requires backpropagation through the energy prediction.

Input: Positions + Atom Types

↓

Embedding Layer (atom types → type-0 features)

↓

┌─────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Equivariant Message Passing Layer │

│ ├─ Spherical harmonic edge embed │

│ ├─ CG tensor product │

│ ├─ Radial weighting │

│ └─ Neighbor aggregation │

└─────────────────────────────────────┘

↓ (repeat N times)

Nonlinearity (gated or scalar-only)

↓

Output Layer (type-0 for energy, type-1 for forces)

Modern Architectures

The mathematical framework described above—spherical harmonics, irreps, CG tensor products, and radial functions—underlies a family of architectures that have progressively pushed the accuracy and efficiency frontier for 3D atomic systems.

Early Foundations

Tensor Field Networks (Thomas et al., 2018) introduced the foundational framework: spherical tensor features, CG tensor products for combining neighbor features with spherical harmonic edge embeddings, and radial functions for distance weighting. The message-passing equation described in the previous section is essentially the TFN formulation.

Attention-Based Architectures

SE(3)-Transformer (Fuchs et al., 2020) was the first to combine equivariant irreps features with the Transformer attention mechanism, replacing uniform neighbor aggregation with learned attention weights. Equiformer (Liao & Smidt, 2023) refined this with equivariant graph attention and nonlinear message passing, achieving strong results on molecular benchmarks. EquiformerV2 (Liao et al., 2024) scaled to higher degrees by adopting $SO(2)$ convolutions from eSCN (see below) and adding separable $S^2$ activations, achieving state-of-the-art results on the OC20 catalyst dataset.

Data Efficiency and Steerable Message Passing

Spherical tensors are sometimes called steerable features in the machine learning literature, because knowing the Wigner-D matrix lets us predict — or “steer” — exactly how a feature vector changes under any rotation, without recomputing anything from scratch. This steerability is what makes equivariant architectures so data-efficient: since the network already knows how features must transform under rotation, it does not need to learn rotational patterns from data, and every training example effectively teaches the model about all rotated versions of itself.

NequIP (Batzner et al., 2022) demonstrated this concretely. Using the TFN framework with learnable radial functions, gated nonlinearities, and residual connections, NequIP achieved state-of-the-art molecular dynamics accuracy with remarkably small training sets — as few as a few hundred structures. The e3nn library developed alongside NequIP provides a practical toolkit for working with irreps and CG tensor products. SEGNN (Brandstetter et al., 2022) generalized equivariant message passing by using steerable features for both node and edge attributes, enabling richer nonlinear operations through steerable MLPs.

Higher Body-Order Interactions

MACE (Batatia et al., 2022) introduced higher body-order interactions through iterated CG tensor products within a single message-passing step. While earlier architectures construct two-body messages, MACE efficiently encodes many-body correlations connected to the Atomic Cluster Expansion (ACE) framework—particularly important for systems where three- and four-body angular interactions matter.

Efficient $SO(2)$ Convolutions

eSCN (Passaro & Zitnick, 2023) addressed the computational bottleneck of CG tensor products by rotating features to align with each edge direction, reducing the full $SO(3)$ operation to a cheaper $SO(2)$ operation and lowering complexity from $O(L^6)$ to $O(L^3)$. This edge-aligned strategy has been widely adopted. eSEN (Fu et al., 2025) further scaled this approach with Euclidean normalization and systems-level engineering—memory-efficient operations, fused kernels, and balanced compute across degrees.

Scaling to Production

UMA (Wood et al., 2025) builds on the eSEN architecture and was trained on nearly 500 million atomic structures across molecules, materials, and catalysts. It uses a Mixture of Linear Experts (MoLE) to handle diverse DFT settings within a single model, achieving strong performance without fine-tuning. The Orb models (Neumann et al., 2024; v3, 2025) take an alternative approach: rather than enforcing strict equivariance through architecture, they use data augmentation to achieve approximate equivariance, prioritizing inference speed and scalability.

Summary

Spherical equivariant layers represent a synthesis of group theory, representation theory, and deep learning. The key ideas are:

-

Symmetry as a constraint: By building networks that respect the rotational symmetry of 3D space, we obtain models that generalize across all orientations without data augmentation.

-

Spherical tensors: Features are organized by degree (scalar, vector, higher-order), living in the carrier spaces of $SO(3)$ irreps defined by spherical harmonics.

-

Clebsch-Gordan tensor products: These operations combine features of different types while maintaining equivariance, enabling deep networks with complex nonlinear transformations.

-

Separation of radial and angular: Distance information is encoded through invariant radial functions, while directional information is encoded through equivariant spherical harmonics.

-

Message passing on graphs: Local atomic environments are processed through neighbor aggregation, with the framework extending naturally to any point cloud or graph structure.

This framework has enabled remarkable advances in molecular property prediction, force field development, and materials discovery, and continues to be an active area of research as new architectures push the boundaries of accuracy and efficiency.

References

- Thomas, N., et al. (2018). Tensor Field Networks. arXiv:1802.08219.

- Fuchs, F. B., et al. (2020). SE(3)-Transformers: 3D Roto-Translation Equivariant Attention Networks. NeurIPS 2020.

- Batzner, S., et al. (2022). E(3)-equivariant graph neural networks for data-efficient and accurate interatomic potentials. Nature Communications.

- Brandstetter, J., et al. (2022). Geometric and Physical Quantities Improve E(3) Equivariant Message Passing. ICLR 2022.

- Batatia, I., et al. (2022). MACE: Higher Order Equivariant Message Passing Neural Networks. NeurIPS 2022.

- Liao, Y.-L. & Smidt, T. (2023). Equiformer: Equivariant Graph Attention Transformer for 3D Atomistic Graphs. ICLR 2023.

- Passaro, S. & Zitnick, C. L. (2023). Reducing SO(3) Convolutions to SO(2) for Efficient Equivariant GNNs. ICML 2023.

- Liao, Y.-L., et al. (2024). EquiformerV2: Improved Equivariant Transformer for Scaling to Higher-Degree Representations. ICLR 2024.

- Neumann, M., et al. (2024). Orb: A Fast, Scalable Neural Network Potential. arXiv:2410.22570.

- Fu, X., et al. (2025). Learning Smooth and Expressive Interatomic Potentials for Physical Property Prediction. arXiv:2502.12147.

- Wood, B. M., et al. (2025). UMA: A Family of Universal Models for Atoms. arXiv:2506.23971.

- Tang, S. (2025). A Complete Guide to Spherical Equivariant Graph Transformers. arXiv:2512.13927.

- Bekkers, E. (2024). Geometric Deep Learning Lecture Series. UvA.

- Bronstein, M. M., et al. (2021). Geometric Deep Learning. arXiv:2104.13478.

- Duval, A., et al. (2023). A Hitchhiker’s Guide to Geometric GNNs for 3D Atomic Systems. arXiv:2312.07511.

-

There does not seem to be a universally agreed-upon terminology for the vector space on which a group representation acts. Different authors use “carrier space,” “representation space,” or simply “the space $V$.” I use “carrier space” throughout this post to emphasize that this is the space that “carries” the group action—i.e., the space whose elements get transformed by the representation matrices. ↩

-

The term “irreps” is short for “irreducible representations”—representations that cannot be decomposed into smaller independent blocks. They are the atomic building blocks from which all representations can be constructed. In some of the literature, features built from irreps are called “irreps features” and the corresponding layers “irreps-based equivariant layers.” ↩

-

We use real spherical harmonics here, which are real-valued linear combinations of the complex spherical harmonics. Most equivariant neural network libraries use real spherical harmonics because they avoid complex arithmetic while maintaining all the essential transformation properties. ↩

-

Throughout this post, subscript indices on a matrix symbol denote its entries (e.g., $D^{(\ell)}_{mm’}(R)$ is the $(m, m’)$-th entry of $D^{(\ell)}(R)$), and subscript indices on a vector symbol denote its components (e.g., $x^{(\ell)}_m$ is the $m$-th component of $\mathbf{x}^{(\ell)}$). ↩

-

The term “spherical tensor” comes from physics, where it refers to a set of quantities that transform under rotations according to a Wigner-D matrix of a specific degree. In the equivariant neural network literature, these are also called “steerable features” (because we can predict—or “steer”—exactly how they change under any rotation) or simply “type-$\ell$ features.” ↩