Introduction to Quantum Chemistry and DFT

Note: My background is in machine learning, not quantum chemistry or physics. What follows is the result of studying this material over the past few years with Seongsu Kim while working on ML methods for molecular systems. I wrote it as the introduction I wish I had—one that presents quantum chemistry and DFT in language familiar to ML researchers. Corrections are welcome.

Introduction

The central computational problem of chemistry is this: given a collection of atoms — their types and positions — predict the system’s properties. The total energy, the forces on each atom, the electron density, the vibrational frequencies. All of these are, in principle, determined by solving a single equation: the Schrödinger equation.

The difficulty is that the solution — the wavefunction — is a function from \(\mathbb{R}^{3N}\) to \(\mathbb{C}\), where \(N\) is the number of electrons. The domain grows exponentially with system size. The wavefunction cannot be observed directly; we only see its consequences — energies, densities, spectra. In ML terms, it is a latent variable.

Two families of methods tackle this problem, differing in what they approximate:

- Wavefunction theory (Hartree-Fock, coupled cluster, etc.) approximates the wavefunction directly, using structured functional forms to make the exponential-dimensional problem tractable.

- Density functional theory replaces the wavefunction with the electron density — a 3D function that provably determines all ground-state properties — sidestepping the exponential dimensionality.

More recently, deep learning methods have been applied to both families, parameterizing either the wavefunction or the density functional with neural networks. This post introduces these ideas from first principles.

Roadmap

| Section | Why It’s Needed |

|---|---|

| The Schrödinger Equation | Define the problem: an eigenvalue equation whose solution (the wavefunction) determines all properties |

| The Born-Oppenheimer Approximation | Separate the nuclear and electronic problems — this is what gives us the potential energy surface |

| Wavefunction Theory | Approximate the wavefunction directly using structured functional forms |

| Density Functional Theory | Replace the exponential-dimensional wavefunction with the 3D electron density |

| Deep Learning for Quantum Chemistry | Modern neural network approaches to both the wavefunction and the density functional |

The Schrödinger Equation

All of non-relativistic quantum chemistry begins with a single equation. Consider a system of \(N\) electrons at positions \(\mathbf{r}_i \in \mathbb{R}^3\) and \(M\) nuclei at positions \(\mathbf{R}_A \in \mathbb{R}^3\). The time-independent Schrödinger equation is:

\[\hat{H} \, \Psi(\mathbf{r}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{r}_N, \mathbf{R}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{R}_M) = E \, \Psi(\mathbf{r}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{r}_N, \mathbf{R}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{R}_M)\]This equation has three ingredients. The Hamiltonian \(\hat{H}\) is what we know — an operator (denoted by the hat \(\hat{\phantom{x}}\)) encoding the physics: how particles move (kinetic energy) and how they interact (potential energy). Given a particular arrangement of atoms, the Hamiltonian is fully determined. The wavefunction \(\Psi: \mathbb{R}^{3(N+M)} \to \mathbb{C}\) is the unknown — a complete description of the quantum state, encoding where every particle is likely to be found. The energy \(E \in \mathbb{R}\) is what we want — the total energy of the system in that state.

The Schrödinger equation is an eigenvalue problem: applying \(\hat{H}\) to \(\Psi\) returns the same function scaled by \(E\). There are many solutions (many possible quantum states), but the one with the lowest energy — the ground state — is the primary target of most quantum chemistry calculations.

The Hamiltonian

The Hamiltonian is a sum of five terms. Denoting the mass of nucleus \(A\) as \(m_A\) (not to be confused with the number of nuclei \(M\)) and atomic numbers \(Z_A \in \mathbb{Z}\):

\[\begin{aligned} \hat{H} = \; & \underbrace{-\sum_i \frac{1}{2}\nabla_i^2}_{\text{electron kinetic}} \underbrace{- \sum_A \frac{1}{2m_A}\nabla_A^2}_{\text{nuclear kinetic}} + \underbrace{\sum_{i<j} \frac{1}{|\mathbf{r}_i - \mathbf{r}_j|}}_{\text{e-e repulsion}} \\[6pt] & \underbrace{- \sum_{i,A} \frac{Z_A}{|\mathbf{r}_i - \mathbf{R}_A|}}_{\text{e-N attraction}} + \underbrace{\sum_{A<B} \frac{Z_A Z_B}{|\mathbf{R}_A - \mathbf{R}_B|}}_{\text{N-N repulsion}} \end{aligned}\]where we use atomic units (\(\hbar = m_e = e = 4\pi\epsilon_0 = 1\)).1 The first two terms are kinetic energy: the \(\nabla^2\) (Laplacian) operator measures how rapidly the wavefunction curves in space, corresponding to particle momentum. The last three terms are potential energy, depending only on inter-particle distances: electrons repel each other, nuclei repel each other, and electrons are attracted to nuclei. Every term follows from classical physics; the quantum nature enters through the kinetic energy operator acting on the wavefunction rather than on particle velocities.

The Wavefunction

The wavefunction \(\Psi(\mathbf{r}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{r}_N, \mathbf{R}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{R}_M)\) assigns a complex number to every possible configuration of particle positions.2 Its squared magnitude gives the probability density for finding the particles at those positions. All physical observables can be computed as expectation values with respect to \(\lvert\Psi\rvert^2\).

The computational challenge is the electronic part. Even on a modest grid of \(G\) points per spatial dimension, representing the electronic wavefunction requires \(G^{3N}\) numbers — for a single water molecule (\(N = 10\)), this is \(G^{30}\). This exponential scaling is the curse of dimensionality of the quantum many-body problem, and it motivates every approximation that follows.

The Born-Oppenheimer Approximation

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation separates the problem into two parts: first solve for the electrons with nuclei held fixed, then move the nuclei on the resulting energy landscape. This is justified because even the lightest nucleus (the proton) is 1836 times heavier than an electron, and heavier nuclei are thousands of times heavier still — so nuclei move much more slowly — the electrons adjust instantaneously to any nuclear configuration.

-

The electronic problem: Fix the nuclear positions \(\{\mathbf{R}_A\}\) and solve for the electronic wavefunction and energy. The nuclei appear only as an external potential \(v_{\text{ext}}(\mathbf{r}) = -\sum_A Z_A / \lvert\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{R}_A\rvert\) that the electrons move in. The nuclear-nuclear repulsion \(\sum_{A<B} Z_A Z_B / \lvert\mathbf{R}_A - \mathbf{R}_B\rvert\) adds a constant for each configuration.

-

The nuclear problem: Move the nuclei on the potential energy surface (PES) \(E(\mathbf{R}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{R}_M)\) — the electronic energy as a function of nuclear positions.

The electronic Hamiltonian, with nuclear positions fixed, is:

\[\hat{H}_{\text{elec}} = -\sum_{i=1}^{N} \frac{1}{2}\nabla_i^2 + \sum_{i<j} \frac{1}{|\mathbf{r}_i - \mathbf{r}_j|} + \sum_{i=1}^{N} v_{\text{ext}}(\mathbf{r}_i)\]The Born-Oppenheimer separation is what makes molecular dynamics and force fields possible. The PES is the function that molecular dynamics simulates on, that geometry optimizations minimize, and that machine learning force fields approximate. Computing the PES requires solving the electronic problem — the subject of the rest of this post.

Wavefunction Theory

The first approach to the electronic problem is to approximate the wavefunction directly. We need to find the ground-state wavefunction \(\Psi\) — the eigenfunction of the electronic Hamiltonian with the lowest energy. The variational principle guarantees that any trial wavefunction \(\tilde{\Psi}\) gives an upper bound on the true ground-state energy:

\[E_0 \leq \frac{\int \tilde{\Psi}^*(\mathbf{r}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{r}_N) \, \hat{H} \, \tilde{\Psi}(\mathbf{r}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{r}_N) \, d\mathbf{r}_1 \cdots d\mathbf{r}_N}{\int \tilde{\Psi}^*(\mathbf{r}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{r}_N) \, \tilde{\Psi}(\mathbf{r}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{r}_N) \, d\mathbf{r}_1 \cdots d\mathbf{r}_N}\]So we can choose a parameterized family of trial wavefunctions and minimize the energy over the parameters.3 The variational principle is directly analogous to minimizing a loss function: the energy is the loss, the wavefunction family is the model architecture, and a specific choice of parameterized family is called an ansatz4 (plural: ansätze).

The Hartree Product: A Mean-Field Approximation

The simplest ansatz assumes the electrons are independent — the many-electron wavefunction factorizes into a product of single-electron wavefunctions called orbitals (from “orbit” — the quantum analogue of a classical electron orbit around a nucleus):

\[\Psi_{\text{Hartree}}(\mathbf{r}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{r}_N) = \phi_1(\mathbf{r}_1) \cdot \phi_2(\mathbf{r}_2) \cdots \phi_N(\mathbf{r}_N)\]Each orbital \(\phi_i: \mathbb{R}^3 \to \mathbb{C}\) depends on only three coordinates, reducing the problem from one function on \(\mathbb{R}^{3N}\) to \(N\) functions on \(\mathbb{R}^3\). The price is ignoring all correlations between electrons: each electron sees only the average field of the others. In ML terms, this is a mean-field factorization — replacing a joint distribution with a product of marginals.

Antisymmetry and the Slater Determinant Approximation

The Hartree product violates a basic requirement: electrons are fermions, so the wavefunction must be antisymmetric under exchange of any two electrons:

\[\Psi(\ldots, \mathbf{r}_i, \ldots, \mathbf{r}_j, \ldots) = -\Psi(\ldots, \mathbf{r}_j, \ldots, \mathbf{r}_i, \ldots)\]The Pauli exclusion principle — no two electrons can occupy the same quantum state — is a direct consequence of this antisymmetry.5 The simplest antisymmetric wavefunction built from orbitals is the Slater determinant:

\[\Psi_{\text{Slater}}(\mathbf{r}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{r}_N) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{N!}} \begin{vmatrix} \phi_1(\mathbf{r}_1) & \phi_2(\mathbf{r}_1) & \cdots & \phi_N(\mathbf{r}_1) \\ \phi_1(\mathbf{r}_2) & \phi_2(\mathbf{r}_2) & \cdots & \phi_N(\mathbf{r}_2) \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ \phi_1(\mathbf{r}_N) & \phi_2(\mathbf{r}_N) & \cdots & \phi_N(\mathbf{r}_N) \end{vmatrix}\]The determinant automatically enforces antisymmetry: swapping two rows (two electrons) flips the sign, and if two orbitals are identical the determinant vanishes.

Hartree-Fock: Self-Consistent Field Theory

Hartree-Fock (HF) theory finds the best single Slater determinant by optimizing the orbitals \(\{\phi_i\}\) to minimize the total energy. The resulting optimality conditions are the Hartree-Fock equations, a set of coupled eigenvalue problems for the orbitals:

\[\hat{f}(\mathbf{r}) \, \phi_i(\mathbf{r}) = \varepsilon_i \, \phi_i(\mathbf{r})\]where \(\hat{f}\) is the Fock operator — an effective one-electron Hamiltonian. It expands as:

\[\hat{f}(\mathbf{r}) = \underbrace{-\frac{1}{2}\nabla^2}_{\text{kinetic}} + \underbrace{v_{\text{ext}}(\mathbf{r})}_{\text{nuclear}} + \underbrace{\int \frac{\rho(\mathbf{r}')}{\lvert\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}'\rvert} d\mathbf{r}'}_{\text{Coulomb}} - \underbrace{\hat{K}(\mathbf{r})}_{\text{exchange}}\]The first three terms are local: kinetic energy, nuclear attraction, and classical Coulomb repulsion from the electron density. The exchange operator \(\hat{K}\) is non-local — its action on an orbital involves integrating over the product of different orbitals across all of space, unlike the other terms which depend only on the local point \(\mathbf{r}\) — and arises from antisymmetry. Every term in the Fock operator is computable exactly from the orbitals; the limitation of Hartree-Fock is not an unknown term but the single-determinant restriction itself.

Because the Fock operator depends on the orbitals (through the Coulomb and exchange terms), the equations must be solved self-consistently: guess the orbitals, build the Fock operator, solve for new orbitals, repeat until convergence. This self-consistent field (SCF) procedure is a fixed-point iteration, analogous in spirit to the EM algorithm: the orbitals define the effective field, and the effective field determines the orbitals.

Electron Correlation

Hartree-Fock captures roughly 99% of the total energy for most systems, but the remaining 1% — the correlation energy — is comparable in magnitude to chemical bond energies and reaction barriers, making it chemically decisive. The correlation energy is defined as the difference between the exact energy and the Hartree-Fock energy:

\[E_{\text{corr}} = E_{\text{exact}} - E_{\text{HF}}\]Because each electron sees only the average field of the others (as discussed above), instantaneous electron-electron correlations are missing. Post-Hartree-Fock methods — configuration interaction (CI), coupled cluster (CC), Møller-Plesset perturbation theory (MP2, MP3, …) — recover this missing energy using richer ansätze built from multiple Slater determinants. These methods are systematically improvable but expensive, with the “gold standard” CCSD(T) scaling as \(O(N^7)\).

Density Functional Theory

Density functional theory (DFT) sidesteps the exponential complexity of the wavefunction entirely by working with the electron density — a function of only three spatial variables instead of \(3N\).

The electron density \(\rho: \mathbb{R}^3 \to \mathbb{R}_{\geq 0}\) gives the probability of finding any electron at position \(\mathbf{r}\):

\[\rho(\mathbf{r}) = N \int |\Psi(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{r}_2, \ldots, \mathbf{r}_N)|^2 \, d\mathbf{r}_2 \cdots d\mathbf{r}_N\]The density is a marginal: we integrate out all electron positions except one and multiply by \(N\) (since any electron could be the one at \(\mathbf{r}\)). The density is always non-negative and integrates to the total number of electrons: \(\int \rho(\mathbf{r}) \, d\mathbf{r} = N\).

The rest of this section develops DFT in four steps: (1) the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems establish that the density determines everything, (2) the Kohn-Sham approximation decomposes the unknown functional into computable pieces plus one unknown, (3) Jacob’s Ladder organizes the approximations for that unknown piece, and (4) the Roothaan-Hall equations discretize the problem into matrices.

The Hohenberg-Kohn Theorems

DFT rests on two theorems proved by Hohenberg and Kohn in 1964. The first theorem states that the ground-state density uniquely determines the entire Hamiltonian — the density is a sufficient statistic for all ground-state properties.6 The second theorem establishes a variational principle: there exists a universal functional \(F[\rho]\) (a map from functions to scalars, denoted with square brackets) such that the true ground-state density minimizes:

\[E_0 = \min_{\rho} \; E[\rho] \quad \text{subject to} \quad \rho \geq 0, \;\; \int \rho(\mathbf{r}) \, d\mathbf{r} = N\]where the energy functional is:

\[E[\rho] = F[\rho] + \int \rho(\mathbf{r}) \, v_{\text{ext}}(\mathbf{r}) \, d\mathbf{r}\]The problem is that \(F[\rho]\) is unknown — we know the sufficient statistic exists but not the function that maps it to the energy. The history of DFT is largely the history of approximating \(F[\rho]\).

The Kohn-Sham Approximation

In 1965, Kohn and Sham turned DFT into a practical method. The key idea is to introduce a fictitious system of non-interacting electrons with orbitals \(\phi_i: \mathbb{R}^3 \to \mathbb{C}\) (the Kohn-Sham orbitals) that reproduce the true electron density: \(\rho(\mathbf{r}) = \sum_{i=1}^{N} \lvert\phi_i(\mathbf{r})\rvert^2\).

Why orbitals? The density tells us where electrons are, but not how fast they are moving — and kinetic energy depends on the latter. An orbital \(\phi_i\) encodes both: its magnitude gives position probability, and its curvature gives kinetic energy (via \(\nabla^2\)).7 The density \(\rho = \sum \lvert\phi_i\rvert^2\) discards the curvature information, which is why no one knows how to compute kinetic energy exactly from \(\rho\) alone. From the orbitals, it is exact: \(T_s = -\frac{1}{2} \sum_{i} \int \phi_i^*(\mathbf{r}) \nabla^2 \phi_i(\mathbf{r}) \, d\mathbf{r}\). The orbitals thus unlock the dominant piece of \(F[\rho]\), leaving only a small residual to approximate:

\[E[\rho] = \underbrace{T_s[\{\phi_i\}]}_{\text{non-int. kinetic}} + \underbrace{J[\rho]}_{\text{Coulomb}} + \underbrace{E_{\text{xc}}[\rho]}_{\text{xc}} + \underbrace{\int \rho(\mathbf{r}) \, v_{\text{ext}}(\mathbf{r}) \, d\mathbf{r}}_{\text{external potential}}\]\(T_s\), the classical Coulomb energy \(J[\rho] = \frac{1}{2} \iint \frac{\rho(\mathbf{r})\rho(\mathbf{r}')}{\lvert\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}'\rvert} d\mathbf{r} \, d\mathbf{r}'\), and the external potential term are all computed exactly. The sole unknown is \(E_{\text{xc}}[\rho]\), the exchange-correlation (XC) functional, which absorbs the residual kinetic energy (the difference between the true \(T\) and \(T_s\)), exchange from antisymmetry, and correlation beyond mean-field.

The Kohn-Sham Equations

Minimizing \(E[\rho]\) with respect to the orbitals yields single-particle eigenvalue equations — the Kohn-Sham equations8:

\[\hat{f}_{\text{KS}}(\mathbf{r}) \, \phi_i(\mathbf{r}) = \varepsilon_i \, \phi_i(\mathbf{r})\]where \(\hat{f}_{\text{KS}}\) is the Kohn-Sham operator — the DFT counterpart of the Fock operator. It expands as:

\[\hat{f}_{\text{KS}}(\mathbf{r}) = \underbrace{-\frac{1}{2}\nabla^2}_{\text{kinetic}} + \underbrace{v_{\text{ext}}(\mathbf{r})}_{\text{nuclear}} + \underbrace{\int \frac{\rho(\mathbf{r}')}{\lvert\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}'\rvert} d\mathbf{r}'}_{\text{Coulomb}} + \underbrace{\frac{\delta E_{\text{xc}}}{\delta \rho(\mathbf{r})}}_{\text{xc}}\]The first three terms are identical to Hartree-Fock. The difference is in the last term: HF has the non-local exchange operator \(-\hat{K}\), while KS-DFT has the functional derivative of \(E_{\text{xc}}[\rho]\) — a potential (local in the simplest approximations) that replaces exchange and additionally captures correlation effects that Hartree-Fock misses entirely.

Despite this structural similarity in the equations, the two methods minimize different energy functionals. Hartree-Fock minimizes the expectation value of the exact Hamiltonian over single-determinant wavefunctions — all terms are computed exactly, but the ansatz is restricted. KS-DFT minimizes an energy functional that includes the approximate \(E_{\text{xc}}[\rho]\) — the ansatz is not the limitation, the functional is. With the exact \(E_{\text{xc}}\), KS-DFT would yield the exact ground-state energy.

Jacob’s Ladder of Exchange-Correlation Functionals

The exchange-correlation functional \(E_{\text{xc}}[\rho]\) must be approximated. Perdew organized the zoo of approximations into a hierarchy known as Jacob’s Ladder, where each rung uses richer information about the density:

| Rung | Input | Example |

|---|---|---|

| LDA | Local density value \(\rho(\mathbf{r})\) | — |

| GGA | + density gradient \(\nabla\rho\) | PBE |

| meta-GGA | + kinetic energy density \(\tau(\mathbf{r}) = \frac{1}{2}\sum_i \lvert\nabla\phi_i(\mathbf{r})\rvert^2\) | SCAN |

| Hybrid | + exact exchange computed from KS orbitals (as in HF) | B3LYP |

| Double hybrid | + unoccupied KS orbitals | B2PLYP |

Higher rungs are generally more accurate but more expensive. The choice of functional is often the most consequential decision in a DFT calculation — analogous to choosing an inductive bias. No single functional works best for all systems, which is one motivation for learning the functional from data.

From Differential Equations to Matrices: The Roothaan-Hall Equations

The Kohn-Sham equations are differential eigenvalue problems in continuous space. To solve them on a computer, we expand each orbital in a finite set of \(K\) known basis functions \(\chi_\mu : \mathbb{R}^3 \to \mathbb{R}\) (typically Gaussian-type orbitals centered on atoms), turning the problem into a matrix eigenvalue problem — the Roothaan-Hall equations:

\[\mathbf{F} \mathbf{C} = \mathbf{S} \mathbf{C} \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}\]Each orbital is expanded as \(\phi_i(\mathbf{r}) = \sum_{\mu=1}^{K} C_{\mu i} \, \chi_\mu(\mathbf{r})\). Substituting into the KS equations and projecting onto the basis produces the Roothaan-Hall equations. \(\mathbf{C} \in \mathbb{R}^{K \times N}\) contains the expansion coefficients for the \(N\) occupied orbitals, and \(\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}\) is a diagonal matrix of orbital energies. \(\mathbf{S} \in \mathbb{R}^{K \times K}\) is the overlap matrix (\(S_{\mu\nu} = \int \chi_\mu(\mathbf{r}) \chi_\nu(\mathbf{r}) \, d\mathbf{r}\)), which is not the identity because the basis functions are not orthogonal. The approximation improves as \(K\) grows.

\(\mathbf{F} \in \mathbb{R}^{K \times K}\) is the Fock matrix (also called the Kohn-Sham matrix). It is the matrix representation of \(\hat{f}_{\text{KS}}\) in the chosen basis: \(F_{\mu\nu} = \int \chi_\mu(\mathbf{r}) \, \hat{f}_{\text{KS}} \, \chi_\nu(\mathbf{r}) \, d\mathbf{r}\), containing kinetic, nuclear, Coulomb, and exchange-correlation contributions. Just as \(\hat{f}_{\text{KS}}\) determines the orbitals in continuous space, the Fock matrix determines the coefficient vectors in the finite basis.

The density matrix \(\mathbf{P} \in \mathbb{R}^{K \times K}\) is the finite-basis counterpart of the electron density. Its elements are \(P_{\mu\nu} = \sum_{i=1}^{N} C_{\mu i} C_{\nu i}\), or equivalently \(\mathbf{P} = \mathbf{C} \mathbf{C}^\top\). The continuous density is recovered as \(\rho(\mathbf{r}) = \sum_{\mu\nu} P_{\mu\nu} \, \chi_\mu(\mathbf{r}) \chi_\nu(\mathbf{r})\). Because the Fock matrix depends on the density (through the Coulomb and XC terms), and the density depends on the orbitals obtained from the Fock matrix, the equations must be solved iteratively.

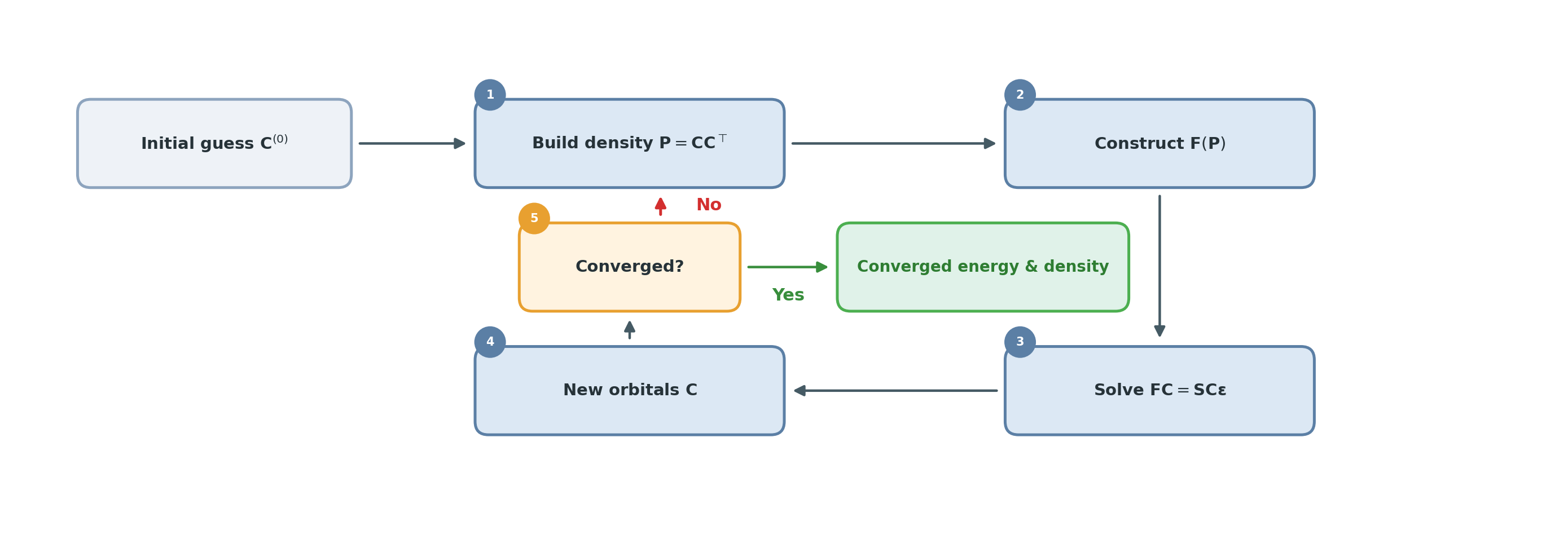

In practice, the SCF loop becomes: guess \(\mathbf{C}\) → build \(\mathbf{P}\) → construct \(\mathbf{F}(\mathbf{P})\) → solve the matrix eigenvalue problem → obtain new \(\mathbf{C}\) → repeat until convergence.

Deep Learning for Quantum Chemistry

The expense of SCF iterations, the unknown form of \(E_{\text{xc}}\), and the desire for models that transfer across chemical space have motivated deep learning approaches on multiple fronts. Neural networks have been applied to both the wavefunction and density functional approaches, either learning the wavefunction or the XC functional directly, or bypassing the SCF iteration by predicting its output.

Neural Network Wavefunctions

Several works parameterize the many-electron wavefunction directly with neural networks, using variational Monte Carlo (VMC) to optimize the energy. The key challenge is enforcing the antisymmetry constraint.

-

FermiNet (Pfau et al., 2020): Parameterizes the wavefunction as a sum of neural network Slater determinants, where the orbitals are functions of all electron positions (not just one), enabling the network to capture correlations beyond a single determinant.

-

PsiFormer (von Glehn et al., 2023): Replaces the FermiNet backbone with a Transformer architecture, using self-attention over electron positions to capture complex many-body correlations more efficiently.

-

Orbformer (Foster et al., 2025): A transferable wavefunction model pretrained on thousands of molecular structures, combining an Electron Transformer with an Orbital Generator to achieve chemical accuracy across diverse benchmarks.

Machine Learning for DFT

On the DFT side, neural networks target different parts of the KS-DFT pipeline: the XC functional, the Hamiltonian matrix, and the electron density.

-

Skala (Luise et al., 2025): Learns the exchange-correlation functional itself from data, replacing the hand-designed functionals on Jacob’s Ladder with a neural network trained on high-accuracy reference calculations.

-

QHNet (Yu et al., 2023), QHFlow (Kim et al., 2025), and HelM (Kaniselvan et al., 2025): Predict the Fock matrix \(\mathbf{F}\) directly from atomic structure, bypassing the SCF iteration. QHFlow uses equivariant flow matching to capture the multi-solution structure of the Hamiltonian, while HelM shows that pretraining on DFT Hamiltonian matrices improves downstream prediction of formation energies and band gaps across the periodic table.

-

DeepDFT (Jørgensen & Bhowmik, 2022), A Recipe for Charge Density Prediction (Fu et al., 2024), ELECTRA (Elsborg et al., 2025), and GPWNO (Kim & Ahn, 2024): Predict the electron density \(\rho(\mathbf{r})\) directly from atomic structure. These methods use graph neural networks, neural operators, and learnable basis sets (including floating orbitals) to estimate the 3D density field without solving the Kohn-Sham equations. Once the density is known, the total energy and forces can be computed from the KS energy functional without solving the eigenvalue problem.

These approaches share a common theme: using neural networks to approximate quantities that are either too expensive to compute exactly or that involve unknown functionals.

Summary

-

The wavefunction encodes everything about a quantum system but lives in an exponentially large space and cannot be observed directly — a latent variable that determines all measurable properties.

-

Born-Oppenheimer separation: Fixing nuclei and solving for electrons gives the potential energy surface — the function that molecular dynamics and force fields operate on.

-

Wavefunction theory: Hartree-Fock approximates the wavefunction as a single Slater determinant, capturing most of the energy but missing electron correlation. Post-HF methods systematically improve on this.

-

Density functional theory: The Hohenberg-Kohn theorems show that the 3D electron density determines all ground-state properties — an extraordinary compression from \(3N\) dimensions.

-

Kohn-Sham DFT: Introduces a fictitious non-interacting system to make the density functional approach practical, concentrating all approximation error in the exchange-correlation functional.

-

Deep learning at every level: Neural networks are being used to parameterize wavefunctions (FermiNet, PsiFormer), learn exchange-correlation functionals (Skala), predict Hamiltonians (QHNet, QHFlow, HelM), and estimate densities (DeepDFT, ELECTRA, GPWNO).

References

- Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. (1964). Inhomogeneous electron gas. Physical Review, 136(3B), B864.

- Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. (1965). Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Physical Review, 140(4A), A1133.

- Kohn, W. (1999). Nobel lecture: Electronic structure of matter—wave functions and density functionals. Reviews of Modern Physics, 71(5), 1253.

- Szabo, A. & Ostlund, N. S. (1996). Modern Quantum Chemistry. Dover Publications.

- Perdew, J. P. & Schmidt, K. (2001). Jacob’s ladder of density functional approximations for the exchange-correlation energy. AIP Conference Proceedings, 577(1), 1-20.

- Pfau, D., et al. (2020). Ab initio solution of the many-electron Schrödinger equation with deep neural networks. Physical Review Research, 2(3), 033429.

- Jørgensen, P. B. & Bhowmik, A. (2022). DeepDFT: Neural message passing network for accurate charge density prediction. Machine Learning: Science and Technology, 3(1), 015012.

- Yu, H., et al. (2023). Efficient and equivariant graph networks for predicting quantum Hamiltonian. ICML 2023.

- von Glehn, I., et al. (2023). A self-attention ansatz for ab-initio quantum chemistry. ICLR 2023.

- Kim, S. & Ahn, S. (2024). Gaussian plane-wave neural operator for electron density estimation. ICML 2024.

- Kim, S., Kim, N., Kim, D. & Ahn, S. (2025). High-order equivariant flow matching for density functional theory Hamiltonian prediction. NeurIPS 2025 Spotlight.

- Foster, A., et al. (2025). An ab initio foundation model of wavefunctions that accurately describes chemical bond breaking. arXiv:2506.19960.

- Luise, G., et al. (2025). Accurate and scalable exchange-correlation with deep learning. arXiv:2506.14665.

- Huang, B., et al. (2023). Ab initio machine learning in chemical compound space. Chemical Reviews, 121(16), 10001-10036.

-

Atomic units set \(\hbar = m_e = e = 4\pi\epsilon_0 = 1\). In these units, energies are measured in Hartrees (1 Ha ≈ 27.2 eV ≈ 627.5 kcal/mol) and distances in Bohr radii (1 \(a_0\) ≈ 0.529 Å). This simplifies the notation by removing constants from the equations. ↩

-

We suppress spin coordinates for notational simplicity. In full generality, each electron has a spin coordinate \(\sigma_i \in \{\uparrow, \downarrow\}\) in addition to its spatial position, and the wavefunction is \(\Psi(\mathbf{r}_1\sigma_1, \ldots, \mathbf{r}_N\sigma_N)\). The antisymmetry requirement applies to the combined spatial-spin coordinates. ↩

-

In the quantum chemistry literature, these integrals are commonly written in Dirac bra-ket notation as \(\langle \tilde{\Psi} \mid \hat{H} \mid \tilde{\Psi} \rangle\) and \(\langle \tilde{\Psi} \mid \tilde{\Psi} \rangle\). ↩

-

German for “approach” or “starting point.” In physics, an ansatz is a specific parameterized form assumed for the solution — essentially a choice of model architecture. For example, the Hartree product ansatz parameterizes the wavefunction as a product of single-electron orbitals; the Slater determinant ansatz uses a determinant of orbitals. Different ansätze trade off expressiveness against computational cost, just as different neural network architectures do. ↩

-

If two electrons were in the same quantum state, swapping them would leave the wavefunction unchanged, yet antisymmetry demands a sign flip. The only function equal to its own negation is zero — so the probability of finding two electrons in the same state vanishes. ↩

-

In ML terms, the density plays the role of a sufficient statistic: just as a sufficient statistic compresses data without losing information relevant to a parameter, the 3D density compresses the exponentially large wavefunction without losing any information needed to compute ground-state observables. ↩

-

The connection between curvature and kinetic energy comes from the de Broglie relation: a faster electron has a shorter wavelength, so its wavefunction oscillates more rapidly in space. More rapid oscillation means more curvature, and \(\nabla^2\) measures exactly this. High curvature = short wavelength = high momentum = high kinetic energy. ↩

-

Derivation outline: minimize \(E[\{\phi_i\}]\) subject to orthonormality \(\int \phi_i^* \phi_j \, d\mathbf{r} = \delta_{ij}\) by introducing Lagrange multipliers \(\varepsilon_{ij}\) and setting \(\delta \mathcal{L} / \delta \phi_i^* = 0\). The chain rule \(\delta E[\rho]/\delta \phi_i^* = (\delta E/\delta \rho) \cdot \phi_i\) (since \(\rho = \sum_i \lvert\phi_i\rvert^2\)) turns each term of the energy into a contribution to \(v_{\text{eff}}\): \(T_s\) gives \(-\frac{1}{2}\nabla^2 \phi_i\), \(J[\rho]\) gives \((\int \rho(\mathbf{r}')/\lvert\mathbf{r}-\mathbf{r}'\rvert \, d\mathbf{r}') \, \phi_i\), \(E_{\text{xc}}\) gives \(v_{\text{xc}} \phi_i\), and the external potential gives \(v_{\text{ext}} \phi_i\). Collecting terms and noting that the Lagrange multiplier matrix can be diagonalized by a unitary rotation of the orbitals yields the KS eigenvalue equation. ↩